By Hana Z. Alamri

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate special and general education teachers’ attitudes and understanding of the implementation of differentiated instruction (DI) with students who have learning disabilities (LD) in elementary school levels. The results showed important information about teachers’ understanding and perceptions; most of them understood the significance of DI and implemented it during teaching. In addition, the results reveal that there is a connection between teachers’ perceptions and the number of courses taken in DI. Teachers also showed that DI is important for all students and teachers, especially with co-teaching and collaboration teams. Most teachers indicated that the biggest obstacle to successfully implementing DI is that there is a lack of time needed to do the necessary work. This shows that further research should be done in this area to make DI easier for teachers to implement in order for students to receive the full benefits.

General and Special Education Teachers’ Perceptions of the Implementation of Differentiated Instruction in Elementary Classrooms with Learning Disabilities Students

This study recognizes that today’s classrooms include students who learn in different ways and have different needs. Utilizing differentiated instruction allows teachers and other educators to include and to be mindful of all learners (ESL students, special education students, struggling students, students with different interests, and students with cultural diversity).

Although many educators would like to envision their class as being mostly homogenous, with minimal insignificant differences from one student to the next, most classrooms are typically closer to this:

One student is a writer beyond her years; another has trouble stringing two sentences together but can solve complex math problems. One student would like to be invisible and another wants to be noticed every minute of the day. Several students race through their work to be the first one finished, but one child wears out erasers in an effort to make every letter perfect and needs extra time to complete an assignment. Four students receive support for their learning disabilities, three are English-language learners, one child has Asperger’s syndrome, and one has attention deficit disorder. (Levy, 2008, p. 161)

A teacher who has not been trained in differentiated instruction would view this fairly typical classroom as an utter nightmare. However, an educator who is well trained in differentiated instruction methods will view this as more of a challenge. Moreover, they will feel fully prepared to do the work to take on this challenge. However, it is still unclear as to what factors contribute to many educators’ ability to successfully implement differentiated instruction. I wanted to explore the perceptions of both special and general education instructors on the implementation of differentiated instruction within both inclusive general education classrooms and special education classrooms.

Statement of Research Problem

Although evidence supports the fact that differentiated instruction is beneficial to students at every level, there are several factors that stand in the way of its implementation. “Teaching a mixed-ability class is a difficult and complex issue for today’s educators” (Dixon, 2014, p. 2). A basic understanding of the concept of differentiated instruction is not enough for a teacher to easily overcome such obstacles. It is necessary for teachers to build a thorough understanding and sincere belief in the benefits of differentiated instruction for it to be effective. Since differentiated instruction training is a fairly recent innovation, it can be difficult to gauge how well more experienced teachers view or understand differentiated instruction. For example, a veteran educator might initially reject the idea of implementing differentiated instruction by claiming that they already know how to teach a classroom. They might take months or even years to finally integrate differentiated instruction into their classrooms, if they ever do. Even then, this can probably only be achieved through very intense training and professional development (Hewitt & Weckstein, 2012, p. 35). However, the importance of making these changes is immense. Therefore, it is essential that, as educators, we understand how most teachers perceive differentiated instruction within inclusive and special education classrooms in order to know if more of this kind of training would be beneficial.

Research Question

It is worth investigating general and special elementary education teachers’ understanding of and attitudes towards differentiated instruction within inclusive and special education classrooms with learning disabilities students in order to know whether further training is necessary. “Historically, general education teachers have not reacted favorably to the increased mainstreaming of students with mild disabilities” (Bacon & Shulz, 1991; Larrivee & Cook, 1979; ctd. in Bender, Vail, & Scott, 1995, p. 87). Special education teachers are often more informed on the methods and benefits of differentiated instruction because their training is more centered on classrooms that are extremely diverse. So, although some general education teachers might not believe that research on differentiated instruction is important in their line of work, “they can still be taught to use evidence-based practices effectively” (Ernest, et al. 2011, p. 192). I would like to know whether more extensive education on differentiated instruction will positively change or affect general and special education teachers’ perceptions on the practice within inclusive and special education classrooms.

My hypothesis is that the more teachers have been educated on differentiated instruction, the more positive their perceptions of it will be. In the past, general education teachers were shown to have negative views towards differentiated instruction, particularly within inclusive classrooms.

“In contrast, more recent research has indicated a more favorable perception of mainstreaming services by general education teachers” (Whinnery, Fuchs, & Fuchs, 1991; ctd. in Bender, Vail, & Scott, 1995, p. 87). It is worth examining whether a significant difference in perceptions still exists between those educators with more training and understanding of differentiated instruction and those with less. Although there are other variables such as the size and the length of the class and types of disabilities that can affect teacher perceptions of differentiated instruction, I believe that, in general, teachers with more education on DI will also have more positive perceptions of its implementation.

Literature Review

In order to understand the importance of differentiated instruction, it is necessary to first define it accurately. According to researchers, differentiated instruction is “an approach to teaching in which teachers proactively modify curricula, teaching methods, resources, learning activities, and student products to address the diverse needs of individual students and small groups of students to maximize the learning opportunity for each student in a classroom” (Bearne, 1996; Tomlinson 1999; ctd. in, Tomlinson et al, 2003, p. 121). Because differentiated instruction factors in a range of student needs, its implementation requires a very involved and active education. Differentiated instruction differs from other forms of inclusive practices in that it involves teaching a fairly standard curriculum with room for “modification that allows for individualized goals for students with severe intellectual disabilities” (Lawrence-Brown, 2004, p. 37). Thus, the educator must have knowledge about disabilities and student needs.

There are a number of ways that a teacher can prepare for the various idiosyncrasies of a diverse classroom. For example, an adequate foundation for a DI curriculum “must address differing student abilities, learning styles, and interests” (Levy, 2008, p. 162). Thus, a teacher might start the year by conducting questionnaires that gauge students’ interests and learning styles in order to incorporate these into his or her curriculum. Also, when assigning a project/assignment, a teacher can give options to complete it for students who have different interests in topics. This is important due to the fact that the very nature of DI involves conforming curricula and teaching methods to the needs of the students. Therefore, educators must “find out where [their] students are when they come into the process and build on their prior knowledge to advance their learning” (Levy, 2008, p.162). Differentiated instruction is not only useful within the classroom setting, but is also incredibly important during the planning process and throughout student assessment. By developing a curriculum that is unique to every class and even every student, teachers make great strides towards helping students to achieve even greater academic development.

Although DI involves collaboration between general and special education instructors and their students, the primary educator for each student bears the greatest degree of responsibility for ensuring that the needs of the student are met. It is not always easy to convince educators to put in the work towards implementing DI; some strategies that can help educators to adopt DI methods are “professional development, modeling, celebration, and teacher leadership” (Hewitt & Weckstein, 2012, p. 36). If teachers are resistant to change, more involved techniques such as “differentiated supervision, providing ‘required choice’ professional development, and aligning teacher evaluation to the change initiative” can be helpful in giving these recalcitrant teachers the needed push towards accepting and understanding DI (Hewitt & Weckstein, 2012, p. 36).

Although certain people analyzing differentiated instruction might claim that it places “an unfair burden on the classroom teacher” (Broderick, Mehta-Parekh, & Reid, 2005, p. 196), it is clear that this is a necessary burden. It is so necessary because the benefits of differentiated instruction are myriad for everyone involved. But it is important to remember that inclusive differentiated instruction requires that “all teachers are responsive to all learners’ needs” (Broderick, Mehta-Parekh, & Reid, 2005, p. 197). It does not require them to develop a completely new curriculum; rather, it encourages them to be ready to adapt to new or unique situations that might possibly arise due to the heterogeneous nature of the classroom. “The teacher who differentiates instruction will recognize that the context is provoking the situation and will problem-solve to modify the instructions” (Broderick, Mehta-Parekh, & Reid, 2005, p. 197).

Thus, differentiated instruction not only provides benefits to the students, but it also helps to prepare teachers for any situation that they might find themselves in. Teachers are not expected to discover a new curriculum but learn to problem solve and develop flexibility that might not be brought about through standard methods of education.

Research shows that differentiated instruction is effective for all students within the classroom in which it is implemented. Some educators might believe that the only goal of DI is to help special education students. However, “strategies used to differentiate instructional and assessment tasks for English language learners, gifted students, and struggling students were also effective for other students in the classroom” (McQuarrie, McRae, & Stack-Cutler (2008); ctd. in the IRIS Center website, 2010). Thus, the apparent benefits for the students who are at the extreme ends of the learning spectrum also apply to students who are much closer to the typical student. If students without disabilities are struggling, they will remain in a general education classroom but may not receive the most helpful and personalized instruction from a standard curriculum. Additionally, general education students still vary from one to the next in their interests, cultural backgrounds, learning styles, and capabilities. Some might argue that the fairest way to deal with these students is to provide a single curriculum so that all students receive ‘equal’ education. However, “equality of opportunity becomes a reality only when students receive instruction suited to their varied readiness levels, interests, and learning preferences, thus enabling them to maximize the opportunity for growth” (Tomlinson, 2003, p. 120). “In one study, the reading skills of elementary- and middle-school students who participated in a reading program that incorporated differentiated instruction improved compared to the reading skills of students who did not receive the program” (Baumgartner, Lipowski, & Rush (2003), ctd. in the IRIS Center website, 2010) proving that DI is beneficial for all students.

While differentiated instruction proves beneficial for students at every level, “students with learning disabilities received more benefits from differentiated instruction than did their grade-level peers” (McQuarrie, McRae, & Stack-Cutler (2008); ctd. in the IRIS Center website, 2010).Thus, we can see how students who differ most greatly from the standard will receive the greatest benefits from the implementation of differentiated instruction. Moreover, studies have shown that “differentiation can and does make a difference in student achievement in the area of writing, math, and reading” (Dee, 2011, p. 57). So although more expansive empirical studies have yet to be performed on the effect of differentiated instruction on students with learning disabilities, it is clear that those studies that have been done show obvious benefits for its implementation.

Although some might see this difference in apparent benefits as unfair, it is obvious that the standard system of education has slighted special education students throughout history. Since the majority of educational development has focused on improving general education throughout history, we must now shift gears and focus more heavily on special education students in order to allow them to receive the same level of attention and consideration that general education students have received in the past. Special education students will be able to be treated in the same way as the other students as opposed to being isolated and left out from the general education activities. At the same time, focusing on special education students takes nothing away from general education students. Since differentiated instruction has proven to be so beneficial for students at every level, it is essential that it is implemented at the earliest possible grade so that students receive the most benefits from its implementation.

Unfortunately, one of the obstacles that is often in the way of implementing DI is the perceptions that teachers hold about it. Although many teachers might profess that they support the implementation of differentiated instruction, their actual attitudes towards it might not reflect such a high standard of acceptance. This is important to understand because “a general education teacher’s belief regarding his or her personal teaching efficacy may affect the selection of instructional strategies in regular education classes” and “teachers in…general education classrooms…employed very few modifications other than the recommended instructional strategies from the teacher’s instructional manual” (Bender, Vail, & Scott, 1995, p. 88). It is therefore clear that there is a connection between the way teachers perceive DI and the way they implement it within their classrooms. This obstacle should not be considered large enough to stand in the way of working towards effective DI implementation. Although it varies for every individual teacher, education and training for differentiated instruction can dramatically improve educators’ perception of it.

It is particularly helpful if this training is done before teachers enter the workforce because teachers would not have yet settled into a particular way of doing things and would be more receptive to ideas on teaching methods. For example, “intensive preparation affects preservice teachers’ perception of preparedness to teach” (Dee, 2011, p. 57). Thus, training teachers before they enter the workforce allows them to more readily accept DI, but also helps them to feel more adequately prepared to teach.

Although DI has been taught to new educators for several decades, there still seems to be a lack of sincerity or motivation towards working towards successful implementation of it, particularly when it comes to an inclusive classroom. This might be a result of the fact that “implementing differentiation is a course of actions that requires a long-term commitment” and it can be difficult to “ensure the continuity of a philosophy of differentiation” (Weber, Johnson & Tripp, 2013, p. 185). This difficulty can lead motivation and passion for DI to decline, particularly for general education teachers in inclusive classrooms. For instance, studies indicate “that general education teachers report making very few major modifications in instruction to accommodate children with LD or other disabilities” (Munson, 1986; Myles & Simpson 1989; ctd. in Bender, Vail & Scott, 1995, p.88). This might be due, in part, to the fact that “Planning for DI is a complex process which requires…additional work on the teacher’s part” (Tricarico & Yendol-Hoppey, 2012, p. 141). Moreover, it might be due to the fact that “teachers who possess the least amount of teaching experience are most often placed with little support in the most challenged rooms” (Tricarico & Yendel-Hoppey, 2012, p. 140). Since this is true, “their learning to teach process will require that knowledge be developed as one practices the profession” (Tricarico & Yendol-Hoppey, 2012, p. 141). Thus one would imagine that a teacher’s ideas and perceptions regarding the implementation of differentiated instruction in inclusive classrooms would change noticeably over the years as they learn and develop as educators. It is important to examine whether teachers still maintain such apathetic or uneducated perceptions of DI in inclusive classrooms as previous studies have shown so that we can work towards fostering the best perceptions and attitudes towards it in the future.

Methodology

Participants

The participants included within this study are nine special and general education teachers in various elementary schools in suburban areas around Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas City, Kansas. The participants were selected dependent upon whether they teach in inclusive or special classrooms with students with learning disabilities. The educators ranged in ages from 20 – 65 and also vary in years of teaching experience. There was no preference given to any race or gender; rather educators were selected based on willingness to participate and the fact that they were working with special education students.

Materials

The materials that were used attempted to assess teacher perceptions towards DI in classrooms with special education students. The first part of the questionnaire asked about the background of the teacher. It included questions about their certification, their education, their age, and other questions relating to the educators’ background (Appendix A). Then, the teachers were asked to respond to several questions in the Likert scale form to determine how positively they viewed DI as well as to determine how much importance they place on certain aspects of DI. The questionnaires were adapted from two previous studies: “Teachers’ Attitudes Toward the Increased Mainstreaming: Implementing Effective Instruction for Students with Learning Disabilities” by Bender, Vail & Scott, 1995 (Appendix B); and “Differentiated Instruction: Begin with Teachers!” by Hewitt & Weckstein, 2012, p. 37-38 (Appendix C). These were adapted to gauge teachers’ attitudes towards implementing DI within their own inclusive classrooms. In addition, I drafted ten interview questions to further understand teacher perceptions of differentiated instruction (Appendix D).

Procedure

In order to collect the information for this study, I first requested the permissions from any authority figures that were necessary for my study. Once my study was approved, I contacted the principals at the participating schools and requested that they give a packet containing my surveys and questionnaires to teachers who met my criteria for participants. These teachers were allowed up to three weeks to fill out the information in the packets after which they were returned to the principal, who passed them on to me. After having received a satisfactory number of survey packets, I conducted an analysis of the data and looked for patterns throughout the interviews that would be useful for my survey. In order to reduce the number of ethical concerns for this study, I made sure to be as unobtrusive as possible. The teachers were not required to complete the survey if they chose not to. They were also allowed to complete the survey on their own time and around two or three weeks. Finally, all surveys were anonymous to protect participants.

Data Analysis

I assigned points for each of the various answers on the questionnaires. I gave 1 point for completely disagree, 2 points for somewhat disagree, 3 points for neutral, 4 points for somewhat agree, and 5 points for completely agree. To analyze the data, I wanted to find the measure of central tendency for the teacher perceptions. I first calculated the mean score for all of the participants for tables one and two. I then calculated the more specific averages for both special and general education teachers separately. Additionally, I calculated the standard deviation from the mean in order to reveal how much the teachers seemed to differ in their responses and scores.

One of the questionnaires was thrown out due to the fact that the teacher did not complete it fully. I also constructed a table using Microsoft Excel that revealed the average score for each teacher. In addition, I tried to determine which questions in the surveys most often yielded lower scores. Finally, I read through the interview questions. As I read through these questions I compared the responses to numbers of courses taken in DI and experience of the educators who were responding. I tried to use my own logical analysis to search for significant responses that seemed to be unanimous between all teachers. I also marked which answers seemed to differ greatly from the norm. I then sat with the information and tried to assess the practical implications of the meaning as well as what kind of responses would be best to address any revealed issue.

Results

The final results of the study revealed a great deal about the way that teachers perceive differentiated instruction and the methods used to implement it within a special education classroom. The average score for special and general education teachers combined was 4.7, with a standard deviation of .4, on both surveys to assess their perceived positivity and negativity concerning DI, the most positive score being 5 and the most negative being 1.

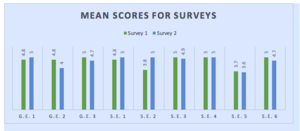

Figure 1: The Average Scores for General (G.E.) and Special Educators (S.E.)

Figure 1 reveals the average score that each teacher received on the survey. G.E. indicates a general education teacher, while S.E. indicates a special education teacher. Most of the mean scores for the first survey were lowered due to the question that asked the teachers whether they thought that DI was being successfully implemented within their school. The most common question that teachers responded to with lower scores on the second questionnaire was the number of importance that they would place on student interests. When the averages were taken separately, they revealed that the general education teachers actually had a slightly higher score (4.9) than the special education teachers (4.6) in Survey 1 (Appendix B), but special education teachers actually had a slightly higher score (4.8) than the general education teachers (4.6) in Survey 2 (Appendix C). However, I see this as a result of the small sample size and not necessarily significant.

The interview questions provided more insight into the teachers’ thoughts about DI for students with learning disabilities. Every teacher provided an acceptable definition for what DI was, despite the fact that some had minimal education concerning DI in their past. Additionally, some teachers either indicated that they had never created or worked on building a DI curriculum or were unsure of whether or not the curricula they made could be considered DI curricula. Despite this, nearly every teacher mentioned employing DI tactics in the classroom. The number one obstacle that stood in the way of DI implementation according to the teachers was a lack of time. Additionally, when asked who DI benefited, nearly every teacher answered students, and most of them mentioned that it was beneficial for educators as well. For example, one special education teacher who had 40 years of teaching experience and who had taken 12 courses in differentiated instruction stated “ It [DI] tends to benefit both the student as well as the teacher”. In addition, one teacher even said that it was a benefit to everyone except the educators if they do not have enough time to make the plans. This general education teacher had 6 years of teaching experience and 2-3 courses taken in differentiated instruction. Teachers who had taken more than five courses in DI agreed that everyone will benefit from DI, and they agreed with the importance of co-teaching and utilizing a collaboration team to create DI.

It appeared that in general, the more classes or education that a teacher had concerning DI, the more passionate they were about it in their interview responses and the more positive their survey results were. This underlines the importance of thorough education concerning DI. Most teachers recognized the importance of DI for students with learning disabilities in that it usually involves teaching a more personalized curriculum that caters to various learning styles and levels.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it would appear that most teachers view differentiated instruction as being beneficial to all students and students with learning disabilities in particular. This agrees with what research mentioned to and found in the Literature Review in this paper. “DI allows students across the ability continuum to learn at their level” (Tricarico & Yendol-Hoppey, 2012, p. 141). However, many teachers indicated that DI was not being implemented as successfully as it could be within their own schools. Additionally most teachers agreed that DI should be employed in all classrooms, although a few mentioned that teachers should not be necessarily required to do so. One teacher indicated that they believed that an educator could not consider themselves to be truly teaching if they were not employing some form of DI. Moreover, nearly every teacher mentioned that time was one of the main obstacles to the successful implementation if DI. Some mentioned that it placed a burden upon the teacher in that it required them to do extra work in order to successfully implement DI. Therefore, it is clear that more work needs to be done in order to reduce the burden on the educator so that they will be able to successfully implement DI. In order to make DI feasible to be required for all teachers, it is necessary to develop a standard method of implementing it that will be easy and efficient for the teacher to carry out. I believe that one of the best ways to reduce the amount of extra time that a teacher might dedicate to differentiated instruction is for schools to increase the amount of co-teaching or collaboration within classroom settings. This can divide the time between more than one teacher in order to make it simpler for all involved. Moreover, I believe that educating instructors on the benefits of DI, as well as how to implement it, is of the utmost importance. Even after an educator has completed their degrees, they could still benefit from further education concerning DI. Thus, it should be discussed in school meetings or in additional skill-building workshops offered for educators. Finally, in order for students with learning disabilities to receive the greatest benefit from DI, it is important that it be required of all teachers. Thus, it is necessary to do further research into the best methods of implementing DI so that teachers do not feel undue strain in implementing it.

Suggestions for further research: There are certain clear limitations to my own study that further research could benefit from fixing in the future. First and foremost, a larger sample size would be much better to indicate the true views of teachers. Constraints on time and geographical location prevented me from being able to conduct a study as thorough as would be ideal. Moreover, further research could be done to more specifically compare the amount of education that a teacher received about DI to their perceptions of it.

References

Bal, A. P. (2016). The Effect of the Differentiated Teaching Approach in the Algebraic

Learning Field on Students’ Academic Achievements. Eurasian Journal Of Educational Research (EJER), (63), 185-204. doi:10.14689/ejer.2016.63.11

Bender, W. N. (Ed.). (2007). Differentiating instruction for students with learning

disabilities: Best teaching practices for general and special educators. Corwin

Press.

Bender, W. N., Vail, C. O., & Scott, K. (1995). Teachers attitudes toward increased

mainstreaming implementing effective instruction for students with learning disabilities. Journal of learning disabilities, 28(2), 87-94.

Broderick, A., Mehta-Parekh, H., & Reid, D. K. (2005). Differentiating instruction for

disabled students in inclusive classrooms. Theory into Practice, 44(3), 194-202.

Darrow, A. (2015). Differentiated Instruction for Students With Disabilities: Using DI in the

Music Classroom. General Music Today, 28(2), 29-32. doi:10.1177/1048371314554279

Dee, A. L. (2010). Preservice teacher application of differentiated instruction. The Teacher

Educator, 46(1), 53-70.

Dixon, F. A., Yssel, N., McConnell, J. M., & Hardin, T. (2014). Differentiated

Instruction, Professional Development, and Teacher Efficacy. Journal For The

Education Of The Gifted, 37(2), 111-127. doi:10.1177/0162353214529042

De Jesus, O. N. (2012). Differentiated Instruction: Can Differentiated Instruction Provide

Success for All Learners?. National Teacher Education Journal, 5(3), 5-11.

Ernest, J. M., Heckaman, K. A., Thompson, S. E., Hull, K. M., & Carter, S. W. (2011).

Increasing the teaching efficacy of a beginning special education teacher using differentiated instruction: a case study. International Journal Of Special Education, 26(1), 191-201.

Galvan, M. E., & Coronado, J. M. (2014). Problem-Based and Project-Based Learning:

Promoting Differentiated Instruction. National Teacher Education Journal, 7(4), 39-42.

Jones, R. E., Yssel, N., & Grant, C. (2012). Reading instruction in tier 1: Bridging the gaps by

nesting evidence-based interventions within differentiated instruction. Psychology In The Schools, 49(3), 210-218. doi:10.1002/pits.21591

Kaplan, S. N. (2013). Special Schools and Differentiated Curriculum. Gifted Child Today, 36(3),

201-204. doi:10.1177/1076217513487186

Kappler Hewitt, K. k., & Weckstein, D. w. (2012). Differentiated Instruction: Begin with

Teachers!. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 48(1), 35-40. doi:10.1080/00228958.2012.654719

Lawrence-Brown, D. (2004). Differentiated instruction: Inclusive strategies for

standards-based learning that benefit the whole class. American secondary

education, 34-62.

Levy, H. M. (2008). Meeting the needs of all students through differentiated instruction:

Helping every child reach and exceed standards. The Clearing House: A Journal

of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 81(4), 161-164.

McKenna, J. W., Shin, M., & Ciullo, S. (2015). Evaluating Reading and Mathematics Instruction

for Students With Learning Disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 38(4), 195-207. doi:10.1177/0731948714564576

Mills, M., Monk, S., Keddie, A., Renshaw, P., Christie, P., Geelan, D., & Gowlett, C. (2014).

Differentiated learning: from policy to classroom. Oxford Review Of Education, 40(3), 331-348. doi:10.1080/03054985.2014.911725

Patti, A. L., & Garland, K. V. (2015). Smartpen Applications for Meeting the Needs of Students

With Learning Disabilities in Inclusive Classrooms. Journal Of Special Education Technology, 30(4), 238-244. doi:10.1177/0162643415623025

Schumm, J. 1., & Vaughn, S. 1. (1998). Introduction to special issue on Teachers’ perceptions:

issues related to the instruction of students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 213-5.

The IRIS Center for Training Enhancements. (2010). Differentiated

Instruction:Maximizing the Learning of All Students Retrieved on [month, day,

year] from https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/di/

Tomlinson, C. A. (2000). Reconcilable differences: Standards-based teaching and

differentiation. Educational leadership, 58(1), 6-13.

Tricarico, K., & Yendol-Hoppey, D. (2012). Teacher Learning through Self-Regulation: An

Exploratory Study of Alternatively Prepared Teachers’ Ability to Plan Differentiated Instruction in an Urban Elementary School. Teacher Education Quarterly, 39(1), 139-158.

Watts-Taffe, S., Laster, B. (., Broach, L., Marinak, B., McDonald Connor, C., & Walker-

Dalhouse, D. (2012). Differentiated Instruction: Making Informed Teacher Decisions. Reading Teacher, 66(4), 303-314. doi:10.1002/TRTR.01126

Weber, C. c., Johnson, L., & Tripp, S. (2013). Implementing Differentiation. Gifted Child Today,

36(3), 179-186.

About the Author

Hana Z. Alamri works as a lecturer at the Department of Special Education, College of Education, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. Hana graduated from University of Missouri – Kansas City (Missouri, USA) and earned Masters of Arts in Special Education. Previously, Hana earned Bachelor degree of Special Education from King Saud University, Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. Then, Hana worked as a special education teacher at the Special Education Academy – Riyadh

Appendices

Appendix A

Demographics of Special and General Education Teachers

Appendix B: Survey 1

Appendix C: Survey 2

Appendix D: Interview Questions

Appendix E: Example of One of the Participants

Download this Issue

To Download a PDF file version of this Issue of the NASETLD Report –CLICK HERE