By Kathleen A. Boothe, Natalie M. Nenovich, and Marla J. Lohmann

Abstract

Special Educators are often asked to serve as part of the Response to Intervention (RtI) or MTSS (Multi-Tiered Systems of Support) Team, which is responsible for designing interventions to address student academic and/or behavioral challenges. Because behavior is a significant concern in today’s classroom, it is imperative that teachers have strategies that can be used in their classrooms when Tier 1 interventions are unsuccessful. This article will discuss several Tier 2 interventions to be used in your classroom, including mentoring, check-in/check-out, and behavior contracts.

Keywords: Classroom Management, Behavior, Teaching, Elementary Education

Using Tier 2 Small Group Interventions to Reduce Challenging Behaviors in the Elementary Classroom

In their previous article, the authors introduced readers to Tier One interventions for reducing challenging behaviors. In this article, readers will be introduced to Tier 2 interventions, which can be used to target specific behavior challenges in the elementary classroom. Previous research has indicated that teachers spend as much as 50% of their day managing behavior (Witt, VanDerHeyden, & Gilbertson, 2004). Behaviors commonly observed by teachers include (a) noncompliance, (b) physical aggression, (c) bullying, and (d) verbal aggression. For Special Education teachers, one aspect of the job is behavior management for students receiving instruction in the Special Education classroom. Additionally, Special Educators are often asked to serve as part of the Response to Intervention (RtI) or MTSS (Multi-Tiered Systems of Support) Team, which is responsible for addressing student learning and behavior challenges by designing interventions that specifically target those concerns.

Tier 2 interventions should be done in the General Education classroom by the General Education teacher. However, the interventions may be supported by the Special Education teacher or counselor. These individuals may have more training regarding skills and strategies in behavior instruction in order to support the individual needs of the student. The counselor and Special Education teacher may also have more flexibility in their scheduled and, therefore, be more easily able to work with smaller groups of students. It is important to remember that Tier 2 interventions should be used with both General Education and Special Education students.

The strategies discussed in this article are based on the Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) model. PBIS is a multi-tiered system in which educators are proactive in the management of disruptive behaviors. Tier 1 accounts for both school-wide and classroom-wide strategies for preventing misbehavior, while Tiers 2 and 3 provide interventions for those students needing additional behavior support. For more information on Tier 1, you can refer to the authors’ recent article entitled Using Classroom Design to Reduce Challenging Behaviors in the Elementary Classroom. Tier 2 supports will help approximately 15% of the student population and are used for students who are not successful at Tier 1; these students need more intensive interventions. Tier 2 interventions are generally provided in small group settings so individual student needs can be addressed more effectively. Based on the research and their own experiences, the authors recommend five evidence-based practices for designing successful Tier 2 small group, or targeted, behavioral interventions in the elementary school classroom. These strategies include (a) academic supports, (b) self-monitoring, (c) mentoring, (d) check-in/check-out, and (d) behavior contracts.

Academic Supports

Challenging behavior can be the result of a child not having the appropriate behavioral skills, as discussed above, or these behaviors may occur due to a deficiency in the student’s academic skills. Learning and behavior challenges, such as inappropriate social and emotional interactions, often go hand-in-hand (Pierangelo & Guiliani, 2008) and Morrison (2001) suggests that gifted students often exhibit challenging behaviors that are considered unacceptable in the school setting. The first step in helping students manage their behavior is determining if the behavior is a result of a mismatch between instruction and learning needs. If the behavior is determined to be a result of a learning struggle, teachers need to address this gap through academic supports, such as before or after school tutorials, lunch tutorials, small group instruction during class, or modified assignments. For gifted students, boredom with course material that is below their learning levels may lead to challenging behaviors; this can be addressed through the creation of individualized assignments that challenge the student at his learning level.

Self-Monitoring

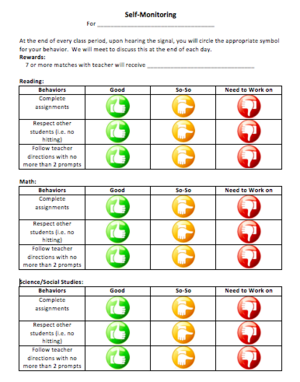

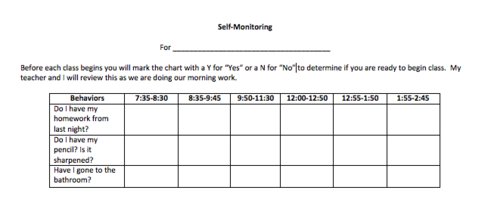

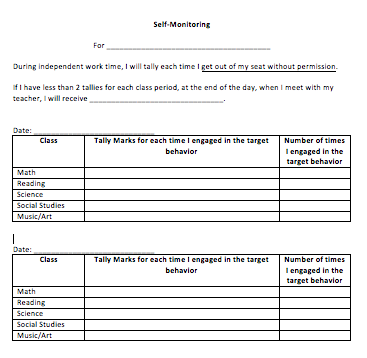

Even young children can, and should, be expected to monitor their own behavior. The purpose of self-monitoring is to allow students to begin to recognize their behavior and when they are occurring. When self-monitoring students will measure their behavior against their target goal. Incentives may be provided as a way to increase use of self-monitoring and appropriate behaviors. There are a variety of ways for children to self-monitor their own behavior. Students can complete a form, provided by their teacher, and at the required intervals mark their behaviors, or they can provide verbal information on their behavior. According to Chafouleas, Riley-Tillman, & Sugai (2007) there are three formats that can be used. These are rating scales, checklists, and frequency charts. Examples of these can be found below in Figures 2 through 4. It is important that you set a schedule for self-monitoring; you should ask yourself if the monitoring will occur at the beginning of class, end of the class period or school day, fixed intervals throughout the day, or at the start or end of an assignment. One example of self-monitoring is seen when the teacher has a bell that ring every 5 minutes; at that time, the children who are self-monitoring will record if they are behaving as expected at that particular moment (Wolfe, Heron, & Goddard, 2000). Students then use this information to create a graph that shows the frequency of their appropriate behaviors; looking at this graph can help students identify the times of day when their behavior is not meeting the expectations (Wells, Sheehey, & Sheehey, 2017). In this example, the bell signifies the cue for students to self-monitor. Choosing a cue that does not include the teacher telling the student it is time to self-monitor is important to this strategy being effective. It is also important that students and teachers have conferences on a regular basis to discuss the self-monitoring process, as well as the data the student is collecting (Falkenberg & Barbetta, 2013). Based on their experience, the authors have found that it is important to explicitly teach students how to self-monitor and to occasionally validate the student’s data by taking data of their own and then comparing the data sets.

Figure 1. Self-Monitoring Rating Scale Form

Figure 2. Self-Monitoring Checklist Form

Figure 3. Self-Monitoring Rating Frequency Chart Form

Mentoring

Many of our students come to school without having positive adult relationships. Additionally, many of our students lack school connectedness (Coyne-Foresi, 2015; Portwood & Ayers, 2005; Sprick, Booher, & Garrison, 2009; Sprick, Garrison, & Howard, 2002). The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2009) defines school connectedness as “the belief held by students that adults and peers in the school care about their learning as well as about them as individuals (p. 3).” Lack of school connectedness and positive adult relationships can be determining factors in why some students misbehave in school.

The use of mentoring has proven to be effective in positively changing student behavior and improving school-connectedness (Caldarella, Adams, Valentine, and Young, 2009; Sprick et al., 2009). Mentoring is about building relationships between adults and students who are at-risk for exhibiting challenging behaviors. According to several researchers, the purpose of mentoring is to create meaningful, relevant relationships between children and adults in order to increase social skills and self-esteem (Caldarella et al., 2009; Dappen & Isernhagen, 2005; Dubois, Neville, Parra, & Pugh-Lilly, 2002). During mentoring, the adult is the person who the student seeks to ask questions, discuss what is going on in their life, and to provide support to the student.

Sprick and colleagues (2009) have identified five steps to successful implementation of mentoring in schools. Step one is to identify volunteers who are willing. These volunteers can be teachers and staff in the building, as well as parent volunteers, students in area colleges, and community members. In one of the author’s experiences her school had volunteers come from one of the local older adult communities and work with students. Additionally, one of the authors was able to have students identify teachers and administrators in the school with whom they wanted to work closely. In the authors’ experience, most of the teachers approached were happy to work with the student, especially knowing the student had asked for him/her specifically. Step two is to identify the students to be involved. In our experience, this is done during the RtI or MTSS process and is possibly done before volunteers have been identified. Step three is to match your students with the appropriate adult. As mentioned above, one author actually received input from the student. Based on their experience, the authors recommend that students are paired with an adult that is not currently one of his/her teachers, but that the student has regular access to when needed. Step four is to provide the students and staff time to meet. One author had this occur during the check-in/check-out process (see below for further discussion on this intervention). Additionally, before and after school and during lunch are also great times for these meetings to occur.

Sprick and colleagues (2009) mention the importance of making sure that everyone knows that these mentoring sessions are voluntary. The meetings should occur about once a week for approximately 10-15 minutes (Sprick et al, 2009). Step five is to make sure that everyone gives the mentoring process time to work. As with any intervention, time is utmost importance. We cannot expect student behavior to change overnight; it will take time and patience is critical. If the student is consistently attending the sessions, teachers can be encouraged that the mentoring is likely effective.

Check-In/Check-Out

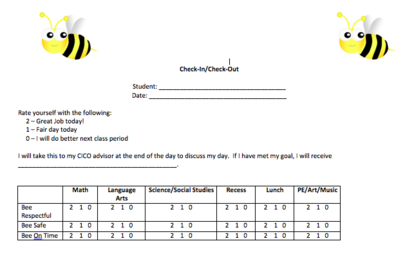

The check-in/check-out (CICO) system is an intervention that combines self-monitoring and mentoring. Check-in/check-out has shown to be effective for about 80% of students utilizing the program (Hawken, Bundock, Barrett, Eber, Breen, & Phillips, 2015). CICO requires little time commitment and can be used with as many as 30 students per teacher (Swoszowski, McDaniel, Jolivette, & Melius, 2013). The CICO process requires the student carry a form to the CICO meetings and the authors have provided an example below (see Figure 4).

An example by one author includes using the CICO three times a day; at the beginning of the day, middle of the day, and the end of the day. In this example, the student meets with a mentor teacher to review their behavior goals, usually 3-4, and to pick-up their behavior checklist. At this time the student and the mentor teacher discuss the reward/incentive for meeting their daily goal. This time is to be used as a time of encouragement and not a time to chastise the student about what they have done wrong in the past. When the student and the teacher meet in the middle of the day, it is just for a quick review of how things are going and what can be done to meet their daily behavior goal. The end of day meeting is used to discuss if they met their goals and receive their reward/incentive if applicable. If the student did not meet their goal, the mentor and the student discuss why this happened and what can be done differently tomorrow. Once again, this should stay a positive, encouraging environment. By keeping these meetings positive and encouraging, the students truly feel as though someone is on his/her side and are more apt to open up, when they know they will not get in trouble. This mentor teacher should not be used as a reactive discipline consequence for the student who uses that mentor teacher for the CICO process.

Figure 4. Check-in/Check-out Form

Behavior Contracts

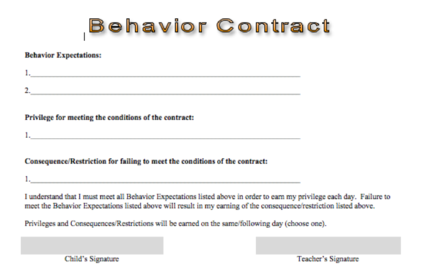

In addition to monitoring their own behavior, elementary-age children can be asked to sign and follow a behavior contract (Bowman-Perrott, Burke, deMarin, Zhang, & Davis, 2015). A behavior contract should be written by both the student and the teacher and should include a behavior goal and clearly outline the consequences for not meeting the goal and the rewards when the student does meet his behavior goal (National Center on Intensive Intervention, 2015). By having the student create these behavior contracts, they begin to take ownership in their behavior(s). Students taking ownership of their behavior lends itself to effective self-monitoring of the behavior, as well as encouraging appropriate behavior. According to Wright (2013), there is a prescribed way to implement behavior contracts. First, you want to meet with your student to negotiate and develop the behavior contract. During this meeting you will want to discuss the undesirable behavior and possible replacement behaviors, as well as rewards and incentives for the student to work towards. Once the contract has been developed, both parties will sign the contract and copies will need to be made. The teacher is then responsible for implementing the behavior contract and utilizing pre-correcting and prompting when necessary. Pre-correction statements are reminders that are provided to students before they are expected to complete an action (Lewis, Colvin, & Sugai, 2000). An example of an appropriate pre-correction statement for an elementary classroom is to thank students for hanging up their coats after recess before you take your class inside. Prompting is all about providing cues to the student to remind them to engage in the appropriate behavior. Figure 5 below is an example of a behavior contract one author used in her elementary classrooms.

Figure 5. Behavior Contract

Conclusion

We understand that teaching is already difficult when you have students who are disruptive and exhibit challenging behaviors. Even with an effective Tier 1 system in place, there will always be a few students who need extra supports in order to be successful. The addition of Tier 2 supports may make all the difference in your classroom. Effective Tier 2 strategies include (a) providing academic supports, (b) having your students engage in self-monitoring of their negative behaviors, (c) providing mentoring in the school, (d) utilizing a check-in/check-out program, and/or (e) using behavior contracts. Implementing both Tier 1 and Tier 2 strategies will work for approximately 95% of your students (Lewis, n.d.) and will help to reduce teacher stress and the challenging behavior of your students.

References

Bowman-Perrott, L., Burke, M.D., deMarin, S., Zhang, N., & Davis, H. (2015). A meta-analysis

of single-case research on behavior contracts. Behavior Modification, 39(2), 247-269.

Caldarella, P., Adams. M. B., Valentine, S. B., Young, K. R., (2009). Evaluation of a mentoring

program for elementary school students at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. New Horizons in Education, 57(1), 1-16.

Cantwell, D.P., & Baker, L. (1991). Association between attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder

and learning disorders. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 24(2), 88-95.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009). School connectedness: Strategies for

increasing protective factors among youth. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Chafouleas, S., Riley-Tillman, C., & Sugai, G. (2007). School-based behavioral assessment:

Informing intervention and instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

Coyne-Foresi, M. (2015). Wiz kid: Fostering school connectedness through an in-school

student mentoring program. Professional School Counseling. doi: 10.5330/1096-2049-19.1.68.

Dappen, L. D., & Isernhagen, J. C. (2005). Developing a student mentoring program: Building

connections for at-risk students. Preventing School Failure, 49(3), 21-25.

DuBois, D. L., Neville, H. A., Parra, G. R., & Pugh-Lilly, A. O. (2002). Testing a new model of

mentoring. New Directions for Youth Development, 93, 21-57.

Falkenberg, C., & Barbetta, P. (2013). The effects of a self-monitoring package on homework

completion and accuracy of students with disabilities in an inclusive general education classroom. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22(3), 190-210.

Hawken, L.S., Bundock, K., Barrett, C.A., Eber, L., Breen, K., & Phillips, D. (2015). Large-scale

implementation of check-in, check-out: A descriptive study. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 30(4), 304-319.

Lewis, T.J. (n.d.). Building a realistic pyramid of instructional and behavioral supports for

prevention and intervention.

vioral-supports-for-prevention-and-intervention.

Lewis, T.J., Colvin, G., & Sugai, G. (2000). The effects of pre-correction and active supervision

on the recess behavior of elementary students. Education and Treatment of Children, 23(2), 109-121.

Morrison, W.F. (2001). Emotional/behavioral disabilities and gifted and talented behaviors:

Paradoxical or semantic differences in characteristics? Psychology in the Schools, 38(5), 425-431.

National Center on Intensive Intervention. (2015). Behavior Contracts. Retrieved from

https://www.intensiveintervention.org/sites/default/files/Behavior_Contracts.pdf.

Pierangelo, R., & Guiliani, G. (2008). Teaching students with learning disabilities: A

step-by-step guide for educators. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Portwood, S. G., & Ayers, P. M. (2005). Schools. In D. L. DuBois, and M. J. Karcher (Eds.)

Handbook of Youth Mentoring (pp. 336-347). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sprick, R. S., & Garrison, M., & Howard, L. (2002). Foundations: Establishing positive

discipline and school wide behavior support (2nd ed.). Eugene, OR: Pacific Northwest Publishing.

Sprick, R., Booher, M., & Garrison, M. (2009). Behavioral response to intervention: Creating a

continuum of problem-solving and support. Eugene, OR: Pacific Northwest Publishing.

Swoszowski, N.C., McDaniel, S.C, Jolivette, K., & Melius, P. (2013). The effects of Tier II

check-in/check-out including adaptation for non-responders on the off-task behavior of elementary students in a residential setting. Education & Treatment of Children, 36(3), 63-79.

Wells, J.C., Sheehey, P.H., & Sheehey, M. (2017). Using self-monitoring of performance with

self-graphing to increase academic productivity in math. Beyond Behavior, 26(2), 57-65.

Witt, J. C., A. M. VanDerHeyden, and D. Gilbertson. 2004. Instruction and classroom

management: Prevention and intervention research. In R. B. Rutherford, M. M. Quinn, and S. R. Mathur, Eds. Handbook of Research in Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

Wolfe, L.H., Heron, T.E., & Goddard, Y.L. (2000). Effects of self-monitoring on the on-task

behavior and written language performance of elementary students with learning disabilities. Journal of Behavioral Education, 10(1), 49-73.

Wright, B. D. (2013). Six evidence behavior interventions prior to or instead of behavior plans

[Powerpoint slides]. Retrieved from https://www.ksde.org/Portals/0/SES/legal/conf12/09a-Browning-Wright-1-NebraskaLaw6Tiers.pdf.

About the Authors

Dr. Kathleen A. Boothe is an Assistant Professor and Program Coordinator of Special Education at Southeastern Oklahoma State University. She has been a district level behavior specialist and a Special Education classroom teacher, where she worked with students with emotional and behavioral disorders. She has done several professional development trainings and conference presentations on the use of PBIS in K-12 schools. Her research interests include implementing PBIS in K-12 schools, and utilizing Universal Design for Learning in the college classroom.

Natalie M. Nenovich, M.Ed, has taught special education in the Plano Independent School District for 14 years, at both the preschool and elementary levels. She received a master’s degree in special education in autism intervention at the University of North Texas, and is currently completing a doctorate in special education at UNT, with a focus on behavioral disorders.

Dr. Marla J. Lohmann is an Assistant Professor of Special Education at Colorado Christian University, where she prepares future teachers in a fully online masters’ degree program. She was previously a self-contained Special Education teacher at the elementary and middle school levels. Her research interests include preschool behavior management, professional collaboration, and best practices in online teacher preparation.

To Access this Article

To download a PDF file version of this issue of NASET’s Classroom Management Series: CLICK HERE