By Natalie M. Nenovich, Marla J. Lohmann, Kathleen A. Boothe, and Kimberly A. Donnell

In their previous articles, authors Natalie M. Nenovich, Marla J. Lohmann, Kathleen A. Boothe, and Kimberly A. Donnell have introduced the topics of Tiers 1 and 2 Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in the early elementary school classroom. This issue of NASET’s Classroom Management series expands on the concept of PBIS by presenting evidence-based interventions for students in Tier 3. These interventions include (a) Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP), (b) social skills training, and (c) rewards and praise.

Abstract

In their previous articles, the authors have introduced the topics of Tiers 1 and 2 Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in the early elementary school classroom. This article expands on the concept of PBIS by presenting evidence-based interventions for students in Tier 3. These interventions include (a) Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP), (b) social skills training, and (c) rewards and praise.

Keywords: classroom management, behavior, teaching, elementary education, positive behavior interventions and supports

Tier 3 Interventions to Reduce Challenging Behaviors in the Elementary Classroom

Teachers spend a significant amount of their time each day managing and addressing challenging behaviors. Research over the past few decades, however, indicates that these behavioral challenges may be reduced through the implementation of a Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) system (Kelm, McIntosh, & Cooley, 2014; Sugai & Horner, 2006). PBIS consists of three tiers for addressing the behavior needs of all students in a classroom or school.

Tier 1 includes universal strategies for all students, while Tiers 2 and 3 are used to meet the specific needs of students exhibiting more challenging behaviors (Sugai & Horner, 2006). Tiers 1 and 2 can be effective for the majority of students, but do not address the needs of the 1%-5% of students who still do not respond. For these students, we implement Tier 3 supports. Students in Tier 3 of PBIS generally receive interventions provided by the Special Education staff. Tier 3 students receive targeted and intensive interventions to handle challenging behaviors that still exist after the implementation of both Tier 1 and Tier 2 interventions.

For more information on Tiers 1 and Tier 2 interventions you can refer to the previous articles written by the authors in the Classroom Management Series, Using Classroom Design to Reduce Challenging Behaviors in the Elementary Classroom and Using Tier 2 Small Group Interventions to Reduce Challenging Behaviors in the Elementary Classroom. Based on the research and their own experiences, the authors recommend three evidence-based practices for designing successful Tier 3 targeted, intensive instruction in the elementary school classroom. The Tier 3 strategies discussed in this article include (a) Functional Behavior Assessments and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP), (b) social skills training, and (c) rewards and praise.

Functional Behavioral Assessment and Behavior Intervention Plan

According to the legal requirements outlined in IDEA, schools are required to conduct a Functional Behavioral Assessment, also known as a FBA, for any student whose behavior is impeding the learning of himself/herself and others. The FBA is used to determine the function of the challenging behavior and to ensure that the implemented interventions address that particular function (Starin, 2011). The most common causes of severe challenging behaviors are a desire for attention and escaping an undesirable activity or request (Anderson, Rodriguez, & Campbell, 2015). In a few cases, inappropriate behaviors are caused by a need for certain sensory stimulation (Starin, 2011).

When conducting an FBA you will first identify and write the target behavior in observational terms. This is important so that anyone reading the target behavior will be able to identify exactly what the problem is. For example, instead of saying “Johnny is disrupting class,” you want to say something like, “Johnny is talking out during instruction.”

Once the target behavior is operationally defined, data collection begins. Data collection should be completed by an outside observer when possible. However, in many schools, it is not possible to have someone outside of the classroom collect the data. In those cases, the Special Education staff should work together to collect data and provide classroom instruction. It is important that data is collected during a time of the day that the behavior is actually occurring. It is also important to collect data during the same time and in the same class each observation period (Scheuermann & Hall, 2016). There are three primary means in which data is collected during the FBA process: (a) indirect data, (b) direct observational data, and (c) manipulation of the environment (Starin, 2011). Indirect data should include a combination of the following: (a) reviewing school records, (b) looking at school histories, (c) reviewing IEP summaries, (d) completing rating scales, and (e) interviews. Both rating scales and interviews should be completed by the teacher, parent, and student when appropriate.

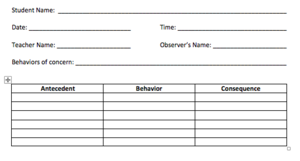

One key component of direct observations is the A-B-C Chart. This takes a look at the targeted behavior and the behaviors that occur directly before and directly after the behavior. Figure 1 below is an example of an A-B-C Chart.

Figure 1. A-B-C Chart

Four additional types of direct data collection include the following: (a) event recording which is used to count the number of instances a behavior occurs, such as the number of times Johnny is out of his seat during independent work time, (b) interval recording to measure high frequency or continuous behaviors to determine if a behavior occurs in a specified amount of time, this could be measuring the time a student is on or off task during a class period,

(c) duration recording used when you want to increase or decrease the length of time a behavior occurs, such as how long a student refuses to comply with a direction by sitting on the floor, and (d) latency recording used when you want to increase or decrease the length of time before a behavior occurs, such as the time between telling a student to get started on her assignment and when they actually get started on the assignment. As with indirect data collection, direct data collection should also include a combination of the A-B-C chart and at least one other direct data collection method.

The IRIS modules, created by Vanderbilt Peabody College and Claremont Graduate University have many examples of both indirect and direct data collection forms. The authors have also found high quality data collection forms on the following websites: (a) www.pbis.org, and (b) www.interventioncentral.org, and (c) www.pbisworld.com. Best practice involves using both indirect and direct data collection in every FBA and use environmental manipulation, also known as functional analysis, when appropriate.

The next step in the FBA process is to create a hypothesis of why the behavior is occurring. This will assist you in determining interventions and replacement behaviors. Creating a hypothesis can be a team effort, including input from all educators who work with the child. Behavior occurs for a reason and generally the cause of the behavior falls into one of the following categories: (a) escaping or avoiding, (b) gaining attention, (c) seeking access to materials, or (d) sensory stimulation. One behavior may serve multiple functions or change within a given environment. Once you have identified the function of the behavior, it is time to develop replacement behaviors. Replacement behaviors need to serve the same function as the inappropriate behavior. The second author noticed that children often yelled to get her attention, so she taught them to calmly walk up to her and wait by her side until she could help them. The end result of both behaviors was attention from the teacher, but waiting patiently was more socially appropriate than yelling across the classroom. Another example is a frustrated student leaving the general education classroom at an inappropriate time when the work became too difficult. To resolve the problem, the teacher taught the student how to appropriately request a break to the water fountain when he gets frustrated. Upon returning to the classroom, the student finishes up his work. When teaching expected behaviors, teachers will also need to create interventions to address the inappropriate/appropriate behavior.

Social Skills Training

Students exhibiting challenging behaviors may be lacking the necessary skills to engage in appropriate behavior. These skills can be taught individually to students or through small group instruction. Tier 3 interventions lend themselves well to creating small groups such as a school “lunch bunch” or an afterschool group. Scheuermann and Hall (2016) found that students who have minimal social skills may be underprepared for the interpersonal demands of school, have poor relationships with peers and teachers, and experience academic and behavioral difficulties. There are three types of social skills problems: (a) acquisition deficits, performance deficits, or fluency deficits. Skills that can be taught during Tier 3 interventions include lessons on self-awareness, cooperation, self-control, stress management, and conflict resolution (Scheuermann & Hall, 2016).

Social skills can be taught in several different ways. Teachers can involve students in discussions, modeling, cooperative learning opportunities, service learning, incorporating the skills into academics, journal writing, behavior contracts, and self-monitoring. These last two ideas are discussed in the author’s previous articles.

Additionally, there are several social skills programs available in which to help teach these skills. These programs include, but are not limited to the following: (a) Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum, (b) Prosocial Skills Development, (c) The PREPARE Curriculum, (d) Tribes, (e) Skillstreaming in the Elementary School, (f) Adolescent Curriculum for Communication and Effective Social Skills, (g) Why Try?, and (h) Zones of Regulation. The first author did not use any specific social skills program, but rather different activity books such as (a) Team Building Activities for Every Group, (b) 104 Activities that Build, (c) Social Skills Activities for Special Children, (d) Ready-to-Use Social Skills: Lessons and Activities Grades 4-6.

Additionally social stories and scripts can be used to help teach appropriate behavior to students in Tier 3. According to Carol Gray (2017), a social story is a “social learning tool that supports the safe and meaningful exchange of information between parents, professionals, and people with autism of all ages.” Several of the authors have used these with success with students with emotional and behavioral disorders. When writing social scripts it is important that you include four types of sentences. The descriptive sentence tells the student where the event occurs and what the students are doing. The perspective sentence will tell the student how others may feel in the situation. Next, directive sentences give the student explicit instructions of what they are to do and say, as well as how to act in a situation. Finally, the control sentence will review with the child what the social story was about. Social scripts are unique to each child and written in concise and concrete terms, giving the child expectations for their behavior in a situation. Figure 2 is an example of a social script created by one of the authors. In this example, the student would assist the teacher in the development of the book. The student and teacher would walk through the steps of the book and take pictures as they went. Walking through the steps and discussing the behavior expectations give the student a reference point for the topic. The pictures would be used in the book as visual reminders. Please note this script does not include pictures, even though a true social script would be enhanced by their inclusion.

Figure 2. Social Script Example

|

Page 1-Descriptive Sentence Everyday my class eats lunch in the cafeteria. |

|

Page 2-Perspective Sentence During lunch, the cafeteria can be loud and make kids feel nervous or scared. |

|

Page 3-Directive Sentence In the cafeteria, “student’s name” will stand in line quietly and be kind to his neighbors. Then, “student’s name” will receive his lunch and find a place to sit. Last, “student’s name” will eat his lunch and talk in a quiet voice. |

|

Page 4-Control Sentence Acting kind and respectful in the cafeteria is important to help “student’s name” classmates feel safe and happy. |

Reinforcement

For many children receiving Tier 3 supports, rewards will be necessary in order to ensure behavior change. While many classrooms include a classroom-wide reward system, some students may need rewards that are tailored to their unique needs. When using reinforcement it is important to have your students complete a reinforcement menu, in which they choose the reinforcement or reward they want to work towards.

One type of reward that has proven to be effective in changing behavior and fits well within a teacher’s limited budget is the use of praise, either verbally or through written notes (Wheatley et al., 2009). It has also been noted in the research and the authors have had success with making sure to provide a 3:1 or 4:1 ratio of positive to negative comments for students with behavior issues. It is important for the social praise to vary and that it be meaningful and effective for the student. Other ways teachers can provide positive social attention is to talk with the student about something they are interested in, something they experienced, or simply ask about the student’s day. Taking time to sit with a child and visit with them without other distractions can be a large reinforcer for many.

For students who are visual learners, having a visual choice board, also called a reinforcement menu, of available choices can be an effective way to alter what reinforcement choice is available at the time. Two websites the authors have used to find reinforcement menus include (a) https://www.pbisworld.com/, and (b) https://www.pbis.org/. Figure 3 below is an example of a reinforcement menu the first author has used in her classroom.

Figure 3. Reinforcement Menu

Additionally, the use of token economies, where the students earn “tokens”, such as fake money, tickets, dots, stickers, marbles, etc. and trade them in at a given time for a reward, can be a valuable motivational tool. Sticker sheets can be adapted to include the student’s interest to increase student engagement. One author used a sticker sheet in which she would give either a sticker or put a highlighter dot on a square for complying with requests. Once the student reached a box with a prize, the student would earn the associated prize. Figure 4 is an example of a sticker sheet used with an early childhood student that had an interest in dinosaurs. After all ten stickers were earned, the student was able to read a book to his mentor teacher.

Figure 4. Sticker Sheet

|

Place Dinosaur Sticker Here |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Another example of a token board is shown in figure 5. The student earns pennies while working on a task. When the student earns all of his/her pennies, they gain access to the reinforcer selected. The teacher has control of the duration it takes to earn each penny. For a younger student learning to use the system, the teacher may want to give a penny for each request given to the child. For older students and students with an ability to work for a longer duration, they may have to complete one entire worksheet or task before earning a penny. Penny boards can also be increased in length so a child might have to earn ten or fifteen pennies to get the reward.

Figure 5. Penny Board

Response cost is another effective reinforcement, but it also acts as a negative consequence. One author created “Panther Buck” to pass out to students who were behaving and following the expectations on their behavior plan, but would also take away money as a consequence to students for not following the behaviors. When using this method, it is important to understand the behavior will worsen before it gets better. It is also important to couple the reinforcement or consequence with a verbal reason for earning or losing the “money”.

Conclusion

When working with students with behavioral challenges it is always important to remember basic behavior principles. Educators should always tell students what behaviors are wanted, rather than repeatedly stating the behavior that is unwanted. Simple language paired with a visual representation can be an effective way to communicate this to children when they are escalated or learning new behaviors. In order to make changes in a student’s behavior, educators must develop a positive rapport with the student and determine what reinforcement will be effective for the student. An individual positive behavior support plan many need to be developed and implemented for a student. This may include a token economy, reinforcement system, and social praise. Educators should select one or two behaviors they want to focus on, and selectively ignore other minor behaviors. Social scripts may be used to teach students expected behaviors. When teachers have students with challenging behaviors, utilizing the above strategies may help alleviate some of the stress of the behavior on both the student and the teacher.

References

Anderson, C.M., Rodriguez, B.J., & Campbell, A. (2015). Functional behavior assessment in

schools: Current status and future directions. Journal of Behavioral Education, 24(3), 338-371.

Gray, C. (2017). What is a social story.

Kelm, J.L., McIntosh, K., & Cooley, S. (2014). Effects of implementing school-wide positive

behavioural interventions and supports on problem behavior and academic achievement in a Canadian elementary school. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 29(3), 195-212.

Scheuermann, B. K., & Hall, J. A. (2016). Positive behavioral supports for the classroom 3rd.

ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Starin, S. (2011). Functional behavioral assessments: What, why, when, where, and who?

Retrieved from https://www.wrightslaw.com/info/discipl.fab.starin.htm.

Sugai, G., & Horner, R.R. (2006). A promising approach for expanding and sustaining

school-wide positive behavior support. School Psychology Review, 35(2), 245-259.

Wheatley, R.K., West, R.P., Charlton, C.D., Sanders, R.B., Smith, T.J., & Taylor, M.J. (2009).

Improving behavior through differential reinforcement: A praise note system for elementary school students. Education & Treatment of Children, 32(4), 551-571.

About the Authors

Natalie M. Nenovich, M.Ed., has taught special education in the Plano Independent School District for 14 years, at both the preschool and elementary levels. She received a master’s degree in special education in autism intervention at the University of North Texas, and is currently completing a doctorate in special education at UNT, with a focus on behavioral disorders.

Dr. Marla J. Lohmann is an Assistant Professor of Special Education at Colorado Christian University, where she prepares future teachers in a fully online master’s degree program. She was previously a self-contained Special Education teacher at the elementary and middle school levels. Her research interests include preschool behavior management, professional collaboration, and best practices in online teacher preparation.

Dr. Kathleen A. Boothe is an Assistant Professor and Program Coordinator of Special Education at Southeastern Oklahoma State University. She has been a district level behavior specialist and a Special Education classroom teacher, where she worked with students with emotional and behavioral disorders. She has done several professional development trainings and conference presentations on the use of PBIS in K-12 schools. Her research interests include implementing PBIS in K-12 schools and utilizing Universal Design for Learning in the college classroom.

Kim Donnell is an early childhood special educator teacher in Piedmont, Oklahoma. She has also taught preschool and first grade in the general education classroom. Currently, she is completing a Master’s in Special Education at Southeastern Oklahoma State University where her emphases are on challenging behaviors and special education admin

To Access this Article

To download a PDF file version of this issue of NASET’s Classroom Management Series: CLICK HERE