Table of Contents

- Special Education Legal Alert. By Perry A. Zirkel

- Buzz from the Hub

- U.S. Department of Education Hosts Raising the Bar: Literacy & Math Series to Address Academic Recovery

- U.S. Department of Education Awards Nearly $120 Million Over Five Years to Support Educators of English Learner Students

- U.S. Department of Education Communicates Vision to Advance Digital Equity for All Learners

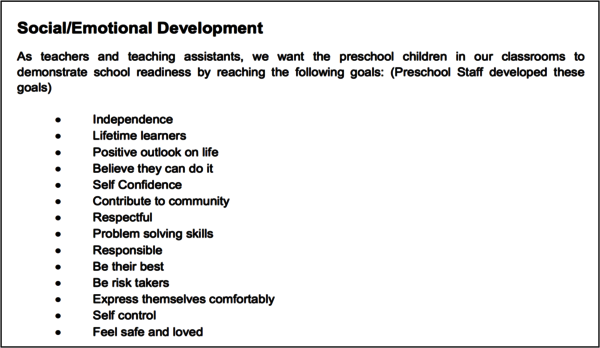

- A Case Study of Compounding Views of Paraprofessional Roles and Relationships in Preschool Classrooms: Implications for Practice and Policy. By Tiara Saufley Brown, Ph.D. and Tina Stanton-Chapman, Ph.D.

- The Scarlet Letter: Applying a Scaffolded Reading Intervention to Engage Reluctant Readers. By Emmett Neno

- Book Reviews:

- Latest Employment Opportunities Posted on NASET

- Acknowledgements

Special Education Legal Alert

By Perry A. Zirkel

© October 2022

This month’s update identifies two recent court decisions addressing two IDEA issues—eligibility determinations and settlement-agreement waivers. For related publications and earlier monthly updates, see perryzirkel.com.

|

On September 20, 2022, a federal district court in New Jersey issued an unpublished decision in P.F. v. Ocean Township Board of Education, addressing the issue of IDEA eligibility for a first grader with an undisputed diagnosis of dyslexia. In response to the parents’ request, the district timely completed an evaluation to determine whether the child was eligible for special education with the classification of specific learning disability (SLD). Under New Jersey law, which permits districts to use either severe discrepancy or RTI for SLD identification, the district used the severe discrepancy approach. The evaluation included (a) testing that revealed the lack of such a discrepancy, (b) consideration of a private diagnosis of dyslexia, which the parents provided and which recommended daily dyslexia remediation incorporating Orton Gillingham methodology, (c) a social assessment that found reading difficulties that neither the social worker nor the child’s teachers linked to dyslexia; and (d) a classroom observation. The resulting multidisciplinary team concluded that the child did not have a SLD that adversely affected her educational performance so as to necessitate special education. In the wake of this determination of IDEA ineligibility and an unsuccessful mediation, the parents filed for a due process hearing. Meanwhile, the district provided general education interventions, including small-group decoding and encoding instruction up to three times per week and small-group reading fluency support twice per week, and, after the parents submitted a diagnosis of ADHD, a 504 plan. After a three-day hearing during the child’s third grade, the hearing officer issued a decision upholding the district’s determination, finding that its evaluation did not rely on a single criterion of a computerized estimator of severe discrepancy and that the child did not meet the three prongs for eligibility: 1-classification, 2-adverse impact, and 3-need for special education. The parents filed an appeal in federal court. |

||

|

First, based on the diagnosis of (a) dyslexia and (b) the use of a computerized estimator, the parents challenged the SLD prong. |

The court concluded that (a) a diagnosis of dyslexia does not necessarily equate to SLD under the IDEA, and (b) the district used the required variety of assessments rather than relying on the computerized program as the sole criterion. |

|

|

Second, the parents disputed the determination that the SLD did not adversely affect the child’s educational performance, pointing to the district’s subsequent determination in grade 3 that she qualified for special education. |

Relying on the “snapshot approach,” the court concluded that, even if the child had a SLD, the relevant information of educational impact was the child’s performance in grade 1, which was satisfactory in level and progress. In contrast, the child’s performance two years later, whereupon the child evidenced the requisite impact and other two required eligibility elements, was not the determinative information. |

|

|

Third, relying on the private evaluator’s recommendations, the parents argued that their child needed special education. |

Rejecting this contention, the court pointed out that the private diagnostician did not specifically recommend IDEA eligibility and, in any event, the parents failed to prove that Orton Gillingham exclusively equated to special education. |

|

|

Although of inconsequential precedential weight, this decision illustrates the continuing judicial trend in eligibility cases, which includes the limited role thus far of RTI as compared to severe discrepancy for SLD and the more general emphasis on the ultimate need prong. |

||

|

On March 15, 2022, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals issued an unpublished decision in N.W. v. Princeton Public Schools Board of Education, addressing the enforceability of release provisions in settlement agreements concerning students with disabilities. To resolve a long-standing dispute with a pro se parent, who was an attorney, the school district entered into a written settlement agreement that included two release provisions—one waiving “any and all claims [the parent and child] have or may have accrued [against the district] … whether known or unknown … through June 30, 2019” and the other indemnifying the district for any claims accrued “through the date of this agreement.” The document also included a provision allowing either side to void the agreement within a three-day window after signing it. At a March 2018 due process hearing to put the settlement agreement on the record, with the parent then signing it, the school district’s representative summarized its provisions, and the parent responded to the hearing officer’s questions to repeatedly confirm that she understood the agreement, including the meaning of these waiver clauses. Although disputing another provision of the agreement within the three-day window, the parent did not take explicit steps to void the agreement when the district refused to modify its language. Instead, the parent contacted the hearing officer to inquire whether the school board had approved the agreement so that she could proceed with her tuition reimbursement under the agreement. Nevertheless, the parent subsequently went to court in an attempt to void the agreement. The federal district court rejected her arguments that the agreement was unenforceable, and she appealed to the Third Circuit. |

||

|

The parent’s first claim was that, because the settlement agreement prospectively waives the child’s educational rights under federal and state law, it is void as contrary to public policy. |

Based on the public policy that settlements promote amicable resolution of disputes and lighten the increasing litigation load, the Third Circuit largely rejected the parent’s claim based on its precedent that broad releases are valid “at least when negotiated by sophisticated parties.” The limited and severable exception was for anti-discrimination laws, which courts have held to be not readily contracted away by private arrangements. |

|

|

The parent’s second claim was that the agreement was obtained through equitable fraud and, thus, unenforceable. |

Based on the record in this case, including the specific terms of the settlement agreement, and the parent’s assurances of her understanding of their scope and meaning, the court found no genuine issue of the requisite material representations for equitable fraud. |

|

|

The parent’s final claim was that the waivers did not meet the Third Circuit’s knowing and voluntary test for waivers, including clear and specific terms, time to reflect upon them, and representation by legal counsel. |

The Third Circuit also rejected this claim, finding that the waiver provisions met the six factors set forth in its 1995 decision in W.B. v. Matula (1995) for knowing and voluntary assent. For example, the court found that this particular settlement agreement was specific and unambiguous; the three-day reconsideration provision provided the requisite opportunity for reflection; and the parent, although pro se, was a practicing attorney. |

|

|

Although not addressing one of the usual IDEA issues for updating, such as identification, FAPE, LRE, or remedies, the limited case law concerning settlement agreements is worth covering here because the vast majority of parents’ filings under the adjudicative avenue of the IDEA are resolved via settlement rather than hearing officer or court decisions. This case shows that such agreements, including any waiver provisions, must be carefully worded and finalized to ensure that they are legally enforceable. |

||

Buzz from the Hub

All articles below can be accessed through the following links:

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-sept2022-issue2/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-sept2022-issue1/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-aug2022-issue2/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-aug2022-issue1/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-july2022-issue2/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-june2022-issue2/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-2022-may/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-april2022-issue1/

Early Childhood Reopening Resource Collection

This CPIR resource collection spotlights materials, videos, and webinars that early childhood programs throughout the country can use to guide their reopening efforts. The majority of the resources have been produced by the 5 early childhood centers funded by OSEP.

Webinar | Sharing Info about State Assessments with Families of Children with Disabilities (Also available in Spanish)

In February, CPIR teamed with NCEO to spotlight NCEO’s amazing new resource, the Participation Communications Toolkit. The highly customizable toolkit is designed for participants to use in discussing and making decisions about how children with disabilities participate in state assessments.

Webinar | Return to School: Development and Implementation of IEPs

This webinar focuses on important guidance from the U.S. Department of Education, entitled Return to School Roadmap: Development and Implementation of IEPs in the LRE. The guidance stresses the importance of revisiting the needs of students with disabilities as they return to classrooms.

Webinar | Providing Required Compensatory Services That Help Students with Disabilities in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

This webinar is a great way to learn when a school district must provide compensatory services under Section 504 and the IDEA to students with disabilities who did not receive the services?to which they were entitled due to the pandemic. How to do so is also discussed.

2022 Determination Letters on State Implementation of IDEA

IDEA requires the Department of Education to issue an annual determination of a state’s efforts to implement the requirements and purposes of IDEA. How did your state measure up?

MHA’s 2022 Back to School Outreach Toolkit

What a wealth of information is in this toolkit! As children go back to school, there are many stressors like the lingering pandemic, gun violence, and social unrest. Check out the Social Media Cheat Sheet, virtual events, resource list, and handouts for adults, children, and teens.

Kids Who Worry They’re Sick When They’re Not

This recent enewsletter from The Child Mind Institute includes 5 stand-alone articles on anxiety and somatic symptom disorders in children: stomach aches and headaches, panic attacks, mental health in children with medical conditions, and behavioral treatment.

All About My Child

(Available in Spanish: Todo sobre mi hijo/a)

This resource is designed to help teachers learn more about each child in their classroom. The sheet asks parents to share info about their child (e.g., likes, dislikes, nickname, languages spoken in the home), using a fun, graphic format.

Partnering With Your Child’s School

(Available in Spanish: Sociarse con la escuela de su hijo)

You and the school share responsibility for your child’s language and literacy learning. Collaborate with the school to make decisions about your child’s literacy education right from the start. Working together promotes faster development and catches trouble spots early.

Scripted Stories for Social Situations

(In multiple languages, including Spanish, Hmong, Ojibwe, & Somali)

These short, adaptable PowerPoint presentations mix words and pictures to communicate specific info to children about social situations such as going to preschool, sitting in circle time, staying safe, and using their words. (From the link, scroll down the page to “Scripted Stories,” click the drop-down on the right, and see the many stories there are! It’s rather amazing.)

Understood Explains: The Ins and Outs of Evaluations for Special Education

Understood Explains is a podcast that unpacks the process that school districts use to evaluate children for special education services. There are 9 separate podcasts in the series, including parent rights, how to request an evaluation of their child, what to expect during (and after) an evaluation, and private versus school-based evaluations.

Getting Dressed

Getting dressed is a wonderful opportunity for young children to build feelings of independence. It is also a wonderful opportunity to embed STEM learning opportunities, such as sequencing, relational concept, matching, or categorizing.

Help Us Calm Down: Strategies for Children

(Also available in Spanish, Ojibwe, Hmong, and Somali)

Try these strategies with your child. The more you use a calming strategy and practice it with your child, the more likely he or she is to use the strategy when experiencing anger, stress, sadness, or frustration.

6 Ways to Help When Your Child is Excluded

Parents may feel powerless when their child is excluded, but there’s actually much they can do to help their child cope and overcome this painful experience. From Great Schools.

There is Power in Friendship Toolkit

Making friends can be hard, especially for children with disabilities. Power in Friendship is designed for families of children with disabilities AND those with typically developing children. It provides resources on how to help your child build inclusive friendships.

How to Help a Disorganized Child

Here’s a simple trick that can turn the most scattered kid into a master of organization.

How to Handle School Refusal

(In Spanish: Rechazo a la escuela: Cómo ayudar a su hijo a superarlo)

When students flat-out refuse to go to school, it can be stressful for both parents and teachers. Different kids resist or refuse school in different ways. Here are tips for parents, caregivers, and educators to manage school refusal, based on what behavior they’re seeing (e.g., crying or tantrums, won’t get dressed, won’t get on the bus or in the car).

A Deeper Look at Anxiety in Kids

This newsletter from the Child Mind Institute consists of separate articles on the subject of anxiety: What are the different kinds of anxiety? How anxiety leads to problem behavior. What is separation anxiety? Selective mutism. Social anxiety. Agoraphobia in children.

13 Bipolar Disorder Symptoms to Be Aware Of

Bipolar disorder, or manic depression, can make it difficult to carry out day-to-day tasks. Here are 13 signs and symptoms to help you know if you or someone you care about should seek treatment.

Video | Supported Decision Making in Health Care and Medical Treatment Decisions

This 8-minute video focuses on helping people with disabilities make decisions about their own health care.

Health and Learning Are Deeply Interconnected in the Body: An Action Guide for Policymakers

As science is showing, the conditions and environments in which children develop affect their lifelong health as well as educational achievement. This guide from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard distills 3 key messages from science that can help guide thinking and policy in a time when innovation has never been more needed in public systems in order to improve both health and learning.

Planning Your Future: A Guide to Transition

The transition to life after high school can be an uncertain time for students with learning disabilities. This guide from NCLD is a tool that students, families, and educators can use to navigate information and prepare for what’s next.

Transportation: Knowing the Options

VR professionals know that most job seekers with disabilities would prefer to travel as independently as possible. If owning and driving a vehicle is not an option, what alternatives exist?

Providing Required Compensatory Services That Help Students with Disabilities in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

This webinar, hosted by Office for Civil Rights (OCR) and OSERS, is a great way to learn when a school district must provide compensatory services under Section 504 and the IDEA to students with disabilities who did not receive the services?to which they were entitled due to the pandemic. How to do so is also discussed.

Back-to-School: Tips for Parents of Children with Special Needs

LDOnline offers 8 back-to-school tips for parents that emphasize communication, organization, and staying up-to-date on special education news.

The Promise and the Potential of the IEP

The Spring-Summer issue of The Special EDge Newsletter is full of articles on the IEP, such as:

Strength-based and Student-focused IEPs;

Improving the IEP: The Parent and Family Perspective;

Collaboration and the IEP; and

What I Learned That Can Help Others, written by a youth speaking for those who cannot.

Prepararse para una reunión de IEP

This 7-minute video in Spanish describes how parents can prepare for an upcoming IEP meeting.

Tools for Tough Times

Much has been said and written about the importance of supporting the mental health of students returning to school in such turbulent times. Now youth speak for themselves in 30 two-minute teen-led videos. They show us all what steps they’re taking to cope with the isolation, anxiety, and uncertainty they’re feeling. You don’t need to be a teen to benefit from the tools they describe.

Adapted PE for Your Child? Dear Parents

Adaptability.com has some information to offer parents on Adapted Physical Education and the rights they have, given that adapted PE is a federally mandated special education service.

An Action-Packed Year for Parent Centers | Here’s the infographic CPIR produced with the data you submitted. It’s 2 pages (designed to be printed front/back to become a 1-page handout or mini-poster). It’s a stunning portrait of what can be achieved by a few, extremely dedicated people for the benefit of so many.

Adaptable Infographic for Parent Centers to Use | This infographic is designed so you can insert just your Center’s numbers, data results, and branding into key blocks of information. Adapt the PowerPoint file, and shine the spotlight on the work of your Center!

Quick Guide to Adapting the Infographic | This 2-page guide shows you where to insert your Center-specific information, just in case having such a “checklist” would be helpful.

PTAs Leading the Way in Transformative Family Engagement

(Also available in Spanish: Las PTA lideran el camino en la participación familiar transformadora)

Drawing from research findings and best practices for family-school partnerships, this 11-page resource explains the guiding principles of the 4 I’s of transformative family engagement (inclusive, individualized, integrated, impactful) and shares strategies local PTAs can use as a model to implement these principles in their school community.

Summer and Sensory Processing Issues

(Also available in Spanish: El verano y los problemas de procesamiento sensorial) | Why can summer be a difficult time for kids with sensory processing issues? What can parents do to help kids stay comfortable in overstimulating outdoor activities?

Ideas to Engage Students with Significant Multiple Disabilities in Activities During the Summer Holidays

Here are fun ideas for summer activities for children with significant multiple disabilities and visual impairment, including sensory trays, art activities, books, music, and toys.

Two more, with titles speakin for themselves?

Babies and Toddlers Indeed!

This landing page serves as a Table of Contents and offers families and others many options to explore, including an overview of early intervention, how to find services in their state for their wee one, parent rights (including parents’ right to participate), the IFSP, transition to preschool, and much more.

Just want an quick step-by-step overview of early intervention?

To give families the “big picture,” share the 2022 update Basic Steps of the Early Intervention Process with families.

For Spanish-speaking families

CPIR offers a landing page called Ayuda para los Bebés Hasta Su Tercer Cumpleaños. Beginning there, families can read about early intervention, the evaluation process for their little one, writing the IFSP, and the value of parent groups and suggestions for where to find them.

10 Basics of the Special Education Process under IDEA

In Spanish (Sobre el proceso de educación especial)

Your Child’s Evaluation (4 pages, family-friendly)

In Spanish (La evalución de su niño)

Parent Rights

In Spanish (Derechos de los padres)

Landing page, again, this time to a simple list of each of the parental rights under IDEA, with branching to a description about that right. Surely a bread-and-butter topic for parents!

All about the IEP Suite

(Similar info about the IEP in Spanish) The landing page gives you and families numerous branches to explore, beginning with a short-and-sweet overview of the IEP, a summary of who’s on the IEP team (with ever-deepening information below and branching off), the content of the IEP (brief summary first, then in-depth discussion thereafter), and what happens with the IEP team meets.

Placement Issues

(Basic info about placement in Spanish) Again, start with the main landing page for this bread-and-butter topic. Take the various branches, depending on what type of info the family is seeking at the moment. Branches include: a short-and-sweet overview to placement, considering LRE in placement decisions, school inclusion, and placement and school discipline.

CPIR Resource Collections and Info Suites

The resources listed above cover just a few of the topics that Parent Centers often address. For a more robust index of key topics, try the Resource Collections and Info Suites resource, which will point you to where other resources on key topics are located on the Parent Center Hub.

Advancing Equity and Support for Underserved Communities

In keeping with President Biden’s Executive Order, signed on his first day in office, federal agencies have now issued Equity Action Plans for addressing equity issues in their individual agency scope and mission. These plans are quite relevant to family-led and family-serving organizations, especially plans from the Departments of Education, Justice, and Health and Human Services.

Fast Facts: Students with disabilities who are English learners (ELs) served under IDEA Part B

OSEP’s Fast Facts series summarizes key facts related to specific aspects of the data collection authorized by IDEA. This newest Fast Facts gives you data details about students with disabilities who are also English learners. (Want to see what other Fast Facts are available?)

Asian Americans with Disabilities Resource Guide

The Asian Americans With Disabilities Resource Guide was designed for Asian American youth with disabilities, allies, and the disability community in mind, in response to the significant information gap about Asian Americans with disabilities. Chapters include Advocacy 101, Accessibility, Culture, Allyship, and Resources.

Strategies for Partnering on Culturally Safe Research with Native American Communities

To identify strategies for promoting cultural safety, accountability, and sustainability in research with Native American communities, Child Trends assessed peer-reviewed and grey literature (e.g., policy documents and guidelines). Findings? To rebuild trust and improve health outcomes, research collaborations with Native American communities must be community-based or community-engaged, culturally appropriate, and recognize tribal sovereignty in the collection and use of data.

Understanding Screening

This toolkit helps educators and parents learn about screening and how screening can help determine which students may be at risk for reading difficulties, including dyslexia. From the National Center on Improving Literacy.

Inside an Evaluation for Learning Disorders

(Also available in Spanish: Un vistazo a una evaluación para los trastornos del aprendizaje)

If a child is struggling in school, the first step to getting help is an evaluation. A learning evaluation can give parents and the child’s teachers valuable information about the child’s strengths and weaknesses. It can also reveal what kind of support would be helpful. A full evaluation is necessary for a child to be diagnosed with a learning disorder. To help parents understand the process, the Child Mind Institute and Understood.org teamed up to create this 20-minute video that walks us through the evaluation process.

U.S. Department of Education Hosts Raising the Bar: Literacy & Math Series to Address Academic Recovery

As part of the Biden-Harris Administration’s ongoing efforts to support the academic recovery of students from the impact of the pandemic, the U.S. Department of Education will host five sessions focused on strategies and programs to boost student literacy and math outcomes.

These sessions will highlight strategies and best practices to help states, districts, and schools improve learning outcomes for students especially in literacy and mathematics. The series seeks to build engagement from the field; identify collaboration opportunities among research, practice, and funding; and lift best practices and resources for practitioners and policymakers to take action to address learning loss and academic recovery.

“We always knew the pandemic would have a profound impact on students’ learning, which is why the Biden-Harris administration made it a priority from Day One to safely reopen our schools and secure the American Rescue Plan’s $122 billion investment in public education to support students’ recovery,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona. “From that moment on, our Department has encouraged state and local leaders to spend their American Rescue Plan dollars on evidence-based strategies for ensuring our students can catch up in the classroom. I’m pleased to announce a new expert-led speaker series that will equip educators, school leaders, and district administrators with the latest information on the science of learning and the most promising tools for accelerating academic recovery, so that they can raise the bar to support our students and level up their skills in the critical areas of math and reading.”

The sessions will occur monthly from October through February and will center on sustained, cohesive efforts to improve educational practice. The kickoff event on Oct. 26, hosted at the U.S. Department of Education, is a continued call to action to practitioners, education leaders, teachers, parents, students, and policymakers to continue to leverage the extraordinary level of available federal resources to mitigate learning loss and accelerate academic recovery.

Additionally, next week the Department will issue a guide to drive strategies in districts and states on how to best address learning loss and academic recovery. This guide will be a follow-up to the extensive guidance provided in the handbooks on reopening and recovery provided by the Department in early 2021.

The subsequent four convenings include topics focused on:

- Learning research-based practices from content experts

- Highlighting promising practices from SEAs and districts

- Leveraging ARP funding to implement literacy and math achievement best practices at scale

- Offering dedicated time and expertise to support action planning (i.e., guided working sessions and support from technical assistance providers).

More information on the additional convenings to come.

|

|

Date |

Session Topic |

|

Session 1 |

October 26, 2022 |

Enhancing Awareness of the Best Strategies and Resources Available to Address Learning Loss and Academic Recovery |

|

Session 2 |

November 10, 2022 (Date is subject to change) |

Best Practices and Research on Rigorous Instruction for all Students in Literacy and Mathematics |

|

Session 3 |

December 8, 2022 (Date is subject to change) |

Increasing Support for Students Beyond the Classroom |

|

Session 4 |

January 12, 2023 (Date is subject to change) |

Addressing Educator Shortages and Parent/Family Engagement in Literacy and Mathematics |

|

Session 5 |

February 9, 2023 |

Highlighting the Best Examples of Putting Policy into Practice |

The Literacy and Math series is part of the Biden-Harris Administration’s commitment to supporting students’ academic recovery and ensuring recovery efforts are meeting student, parent, and family needs. As part of that effort, in January, Secretary Cardona laid out his vision for education in America by boldly addressing opportunity and achievement gaps in education.

Through the American Rescue Plan (ARP), the Biden-Harris Administration is investing in evidence-based solutions that are driving academic recovery and providing additional mental health supports. Since education was disrupted in March 2020 due to the global covid-19 pandemic, the Biden-Harris Administration has prioritized recovery for students through multiple efforts. In addition to providing $130 billion in ARP funds for K-12 education to support the safe reopening of K-12 schools and to meet the needs of all students, the Biden-Harris Administration:

- Awarded nearly $1 billion to 56 states and territories through the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act to help schools in high-need districts provide students with safe and supportive learning opportunities and environments that are critical for their success.

- Launched the National Partnership for Student Success to recruit 250,000 new tutors, mentors, and other adults in high-impact roles, and support states, school districts and community organizations in establishing high-quality programs.

- Launched the Engage Every Student Initiative to support summer learning and afterschool programs with ARP funds, alongside other state and local funds.

- Launched a campaign through the Best Practices Clearinghouse to highlight and celebrate evidence-based and promising practices implemented by states, schools, and school districts using ARP funds to support learning recovery, increased academic opportunities, and student mental health.

- Launched the National Parents and Families Engagement Council to empower parents and school communities with knowledge about how their schools are using and can use federal funds to provide the necessary academic and mental health supports.

- Made it easier for families and stakeholders to see how their states and school districts are using ARP funds by requiring State Educational Agencies and Local Educational Agencies to create plans for using ARP Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds, engage key stakeholders as they draft their plans, and make those plans accessible to the public through an interactive map. Previous rounds of relief funding did not require these plans.

U.S. Department of Education Awards Nearly $120 Million Over Five Years to Support Educators of English Learner Students

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA) recently announced awards of nearly $120 million over five years under the National Professional Development Program (NPD) to support educators of English learner students.

The NPD program provides grants to eligible Institutions of Higher Education and public or private entities with relevant experience and capacity, in consortia with states or districts, to implement professional development activities that will improve instruction for English Learners (ELs). Following the education priorities of the Biden-Harris Administration as stated by Secretary Cardona, these grants align with his call to boldly address opportunity and achievement gaps by investing in, recruiting, and supporting the professional development of a diverse educator workforce, including bilingual educators so education jobs are ones that people from all backgrounds want to pursue.

“I grew up speaking Spanish at home and thrived as an English learner in school thanks to great teachers who helped me realize that my bilingualism and my biculturalism would someday be my superpower,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona. “As our nation grows more diverse than ever before, we must level up our investments in educators who can provide students from all backgrounds with equitable opportunities to succeed. This $120 million, five-year investment will support high quality professional development and teacher preparation programs across the country. It will also help us grow a pipeline of diverse and talented educators who can help more English learners realize their own bilingual and multilingual superpowers.”

These grants can be awarded to educators of ELs including teachers, administrators, paraprofessionals or other educators working with ELs. Professional development activities may include teacher education programs and training that lead to certification, licensing, or endorsement for providing instruction to students learning English.

Educator effectiveness is the most important in-school factor affecting student achievement and success. To improve the academic achievement of ELs, the NPD program supports pre-service and in-service instruction for teachers and other staff, including school leaders, working with ELs. Selected applicants submitted proposals to improve access to culturally and linguistically responsive early learning environments for multilingual learners and that increase public awareness about the benefits of proficiency in more than one language.

“The NPD grants support the professional growth of the education workforce by promoting the skills and critical dispositions of educators and leaders. These grants can enhance the capacity of the education workforce to create equitable learning environments that promote language, literacy and diversity. This work is vital to increase educator effectiveness in meeting the needs of English learners?and their families,” said OELA Acting Director Montserrat Garibay.

The NPD program has funded a range of grantees that are currently implementing 182 projects across the country, including the most recent grantees. As the EL population continues to grow, it has become increasingly important to identify and expand the use of evidence-based instructional practices that improve EL learning outcomes.

The Department projects this new cohort of 44 grants will serve approximately 1,638 pre-service and 6,271 in-service teachers.

A full list of awards can be found below:

|

Name |

State |

Total Granted Over 5 Years |

|

The University of Alabama in Huntsville |

AL |

$2,799,244 |

|

University of Alabama at Birmingham |

AL |

$2,985,871 |

|

University of Arkansas System |

AR |

$2,955,256 |

|

San Diego State University Foundation |

CA |

$2,947,479 |

|

The Regents of the University of California, Los Angeles |

CA |

$2,944,015 |

|

California State University San Marcos Corporation |

CA |

$3,000,000 |

|

California State University, Dominguez Hills Foundation |

CA |

$2,571,938 |

|

The Regents of the University of Colorado |

CO |

$2,822,251 |

|

University of Delaware |

DE |

$2,666,354 |

|

University of South Florida |

FL |

$2,061,703 |

|

The Florida International University Board of Trustees |

FL |

$2,503,029 |

|

The University of Central Florida Board of Trustees |

FL |

$2,603,976 |

|

Florida Atlantic University |

FL |

$1,788,835 |

|

University of Northern Iowa |

IA |

$1,489,701 |

|

Trustees of Indiana University |

IN |

$2,999,075 |

|

Kansas State University |

KS |

$2,940,478 |

|

University of Kansas Center for Research, Inc. |

KS |

$2,290,405 |

|

University of Massachusetts Boston |

MA |

$2,946,798 |

|

Lasell University |

MA |

$2,504,012 |

|

Trustees of Boston University |

MA |

$2,868,044 |

|

National Association for Bilingual Education |

MD |

$2,965,801 |

|

Grand Valley State University |

MI |

$2,705,208 |

|

Western Michigan University |

MI |

$2,969,991 |

|

Wayne State University |

MI |

$2,289,939 |

|

Southeast Service Cooperative |

MN |

$2,716,643 |

|

William Paterson University of New Jersey |

NJ |

$2,863,634 |

|

The College of New Jersey |

NJ |

$2,998,231 |

|

Board of Regents, NSHE obo Nevada State College |

NV |

$2,004,285 |

|

University of Cincinnati |

OH |

$2,963,816 |

|

University of Oregon |

OR |

$2,992,611 |

|

Western Oregon University |

OR |

$2,989,591 |

|

Temple University – Of The Commonwealth System of Higher Edu |

PA |

$2,998,194 |

|

Cabrini University |

PA |

$2,981,534 |

|

Clemson University |

SC |

$2,332,682 |

|

BakerRipley |

TX |

$3,000,000 |

|

The University of Texas at El Paso |

TX |

$2,831,807 |

|

Region 18 Education Service Center |

TX |

$2,812,771 |

|

Texas A&M University |

TX |

$3,000,000 |

|

Stephen F. Austin State University |

TX |

$2,530,139 |

|

University Of North Texas at Dallas |

TX |

$2,761,155 |

|

Weber State University |

UT |

$2,787,029 |

|

Western Washington University |

WA |

$2,588,559 |

|

University of Washington |

WA |

$2,995,811 |

|

Board of Regents of UW-System on behalf of UW-Milwaukee |

WI |

$2,870,290 |

|

Total |

|

$119,638,185 |

DU.S. Department of Education Communicates Vision to Advance Digital Equity for All Learners

Today, during the National Digital Equity Summit hosted by the U.S. Department of Education, the Office of Educational Technology (OET) launched Advancing Digital Equity for All: Community-based Recommendations for Developing Effective Digital Equity Plans to Close the Digital Divide and Enable Technology-Empowered Learning. This resource provides recommendations for equitable broadband adoption to support leaders crafting digital equity plans, an aspiration that became an emergency for many schools and families during the pandemic. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed earlier this year supports that goal, allocating $2.75 billion under the Digital Equity Act to ensure that all people and communities can reap the full benefits of the digital economy.

“Digital equity has never felt more urgent. But our opportunity to deliver digital equity has never felt more within reach. The pandemic turned equitable access to technology from an aspiration into an emergency,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona. “Students without broadband access or only a cell phone have lower rates of homework completion, lower grade point averages … even lower college completion rates. Today, there can be no equity without digital equity. Thanks to President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, we’re making tremendous progress towards that goal.”

The National Digital Equity Summit will convene nearly 200 equity-minded organizations, state and local systems leaders, federal agencies, and educational technology experts to discuss how broadband investments from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law can be leveraged to better serve students furthest from digital opportunities and close the digital divide, thereby supporting transformative learning experiences empowered through technology. The summit will be livestreamed and can be viewed here.

“The pandemic illuminated long-standing educational equity gaps and spurred an unprecedented period of emergency remote learning.?One of the most critical challenges during this time has been providing the foundational access to high-speed, reliable internet necessary to facilitate everywhere, all-the-time learning,” said Assistant Secretary for Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Roberto Rodríguez. “We’ve all understood that digital equity is no longer a ‘nice-to-have’ condition, but a ‘must-have’ to ensure that all may fully participate in the digital economy and society of today and tomorrow.”

The new publication also highlights existing barriers across the three components of availability, affordability, and adoption, and provides examples of promising strategies to overcome these barriers.?Much of the content was gathered through the Digital Equity Education Roundtables (DEER) Initiative launched by OET in the spring, which progressed national conversations with leaders from community-based organizations, as well as families and students furthest from digital opportunities, to learn more about the barriers faced by learner communities and promising solutions for increasing access to technology. During these events, participants expressed the need to address the three components of digital equity — availability, affordability, and adoption – in order to serve all learners in an equitable manner. Key takeaways from participants are captured in the new Advancing Digital Equity for All resource.

The DEER Initiative, today’s summit, and the new resource are examples of the commitment from the Biden-Harris Administration to address connectivity barriers around the country. Also, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Education Cindy Marten recently attended a roundtable discussion in Charlotte, North Carolina, hearing directly from school leaders, community-based organizations, and parents about efforts necessary to boost participation in the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP). Additionally, the Department engaged in a back-to-school campaign to promote ACP enrollment, contributed to interagency efforts in streamlining information about federal broadband funding, and published a series of resources to ensure students’ access from home.

Over the next year, OET will build on this progress by fostering a sense of urgency around adoption barriers that impede digital equity in education and cultivating a community of champions who are implementing solutions.

For the latest information on OET’s digital equity efforts, visit DEER – Office of Educational Technology.

A Case Study of Compounding Views of Paraprofessional Roles and Relationships in Preschool Classrooms: Implications for Practice and Policy

Tiara Saufley Brown, Ph.D.

James Madison University

Tina Stanton-Chapman, Ph.D.

University of Cincinnati

Abstract

The purpose of this qualitative case study is to extend a previous study by Brown & Stanton-Chapman (2014) by exploring the dynamics between teachers and paraprofessionals in preschool classrooms. Specifically, researchers examined the relationship between eight paraprofessionals’ perspectives of job responsibilities and satisfaction in comparison to their assigned eight teachers’ perspectives of these same ideas. Data collection included semi-structured interviews of the 16 participants as well as classroom observations and document collection. Four key themes emerged from data collection: responsibilities are often influenced by the level of teacher and paraprofessional motivation; paraprofessionals often assimilate to match the lead teacher’s demeanor and perspectives; teachers and paraprofessionals view recognition and appreciation very differently; and the majority of classroom outcomes are primarily influenced by structured school policies. Considering these findings, implications for practice and directions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: paraprofessional, teaching assistant, educational assistant, relationship, preschool

A Case Study of Compounding Views of Paraprofessional Roles and Relationships in Preschool Classrooms: Implications for Practice and Policy

When 28 parents of children with disabilities were asked about paraprofessional supports for their child, 25 percent reported that paraprofessionals made inclusion in school possible (Werts, Harris, Tillery, & Roark, 2004). Additionally, 61 percent of the sample said their child spoke of the paraprofessional at home as much as he or she did about the classroom teacher (Werts et al., 2004). This finding is supported by a rich body of evidence that emphasizes the importance of paraprofessional relationships with teachers (Blalock, 1991; Burgess & Mayes, 2009), students (Broer, Doyle, & Giangreco, 2005; Healy, 2011) and families (French & Chopra, 1999; Werts et al., 2004). These relationships also play a central role in the academic and social outcomes for student success (Giangreco, Doyle, & Suter, 2012). For example, paraprofessional supports have been linked to increased social interactions among children from different backgrounds (Chopra, Sandoval-Lucero, Aragon, Bernal, De Balderas, & Carroll, 2004) and to an increase in academic achievement in inclusive settings (Giangreco, Smith, & Pickney, 2006). For these reasons, researchers studied the views and perspectives of paraprofessionals to obtain information on their classroom obligations, job fulfillment, and expertise (Giangreco, Edelman, & Broer, 2001). Yet, results have pointed to universally negative perceptions of the job of a paraprofessional due to the low wages, ambiguous responsibilities, and power struggles between paraprofessionals and teachers (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). Researchers studied this phenomenon in order to understand why this job is viewed as undesirable despite the important impact paraprofessionals have in the classroom (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014).

In a recent study of paraprofessional relationships, Brown and Stanton-Chapman (2014) used qualitative observations and interviews in addition to a quantitative survey to explore the relationship between paraprofessionals’ perspectives of their responsibilities and the corresponding satisfaction and issues surrounding their job (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). Three key themes emerged from data analysis: a) there is often confusion over job responsibilities; b) job satisfaction is highly influenced by both monetary compensation and recognition; and c) relational power dynamics exist between teachers and paraprofessionals (Brown and Stanton-Chapman, 2014). And, interestingly, paraprofessionals and teachers viewed key classroom issues very differently. For example, while teachers often felt paraprofessional pay was adequate, paraprofessionals felt undervalued and overworked for the compensation they received (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). Findings also indicated that there were additional divergences between paraprofessional and teacher perspectives including: differences in perceived roles and responsibilities between the two groups, lack of perceived appreciation from the paraprofessional while teachers felt appreciation was adequate, and a back-and-forth exchange between paraprofessional motivation and teacher receptiveness to classroom responsibilities (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). This 2014 study did not explore these views in depth, however, and understanding these differences has potential to inform practice and further understand classroom relationships. The current study will explore this further through an in-depth case study of eight paraprofessionals and eight teachers in order to provide insight into the complexities of teacher and paraprofessional perspectives on multiple classroom issues (Stake, 1994). The present study will also include further analysis of paraprofessional and teacher dynamics and how these perspectives differ between both parties in the five key areas of extant paraprofessional research: skills/experience, job fulfillment, roles and obligations, preparation and coaching, and relationships with teachers and students (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). Findings from the current study hope to further inform researchers and practitioners about vital issues relating to different perspectives among teachers and paraprofessionals. These findings may provide implications for informing job responsibilities, increasing job contentment, and understanding how relationships function in successful preschool classrooms.

Literature Review: Five Key Areas of Paraprofessional Research

There are over one million paraprofessionals in PK-12 classrooms across the United States (Ashbaker, Dunn, & Morgan, 2010). Sometimes referred to as an instructional aide or paraeducator, a paraprofessional is an education employee who may not be licensed to teach but executes numerous classroom duties and collaborates with lead teachers for academic and behavioral support (Department of Education, 2012). Despite this definition, the responsibilities and job requirements vary based on locale (Allen and Ashbaker, 2004). However, there is a growing body of evidence to support paraprofessional efficacy in many roles including: assisting students with disabilities (Werts et al., 2004), collaborating with teachers and parents (Chopra & French, 2004; Giangreco, Smith, & Pickney, 2006), and maintaining and supporting important classroom relationships (Burgess and Mayes, 2009; Lewis, 2004).

Over the past 30 years, a growing body of research has explored multiple aspects of the experiences of paraprofessionals. Several studies investigated paraprofessional assignments with individual students and noted the negative effects paraprofessional-student proximity can have on academic success and peer interactions (Giangreco, Edelman, Broer, & Doyle, 2001; Malmgren & Causton-Theoharris, 2006; Skar & Tamm, 2001). The overarching theme from these studies focused on the idea that paraprofessional-student relationships, and the proximity in which these two groups work, vary and can be both beneficial or detrimental for student success (Malmgren & Causton-Theoharris, 2006; Skar & Tamm, 2001). Similarly, studies in this area have also investigated the over-use of paraprofessionals for multiple classroom tasks including: behavior management, instructional planning and delivery, and contact with families (Broer, Doyle, & Giangreco, 2005; Carter, Cushing, Clark, & Kennedy, 2005). Ultimately, the vast majority of paraprofessional studies focus on five key areas: skills, job fulfillment, roles, preparation, and relationships. This research is succinctly summarized below.

Skill and expertise. Research indicates paraprofessionals often lack important teaching skills, formal education, and hands-on experience (Bolton & Mayer, 2008). Additionally, studies have shown that paraprofessionals are attracted to the job hours and benefits, but they are often underpaid (Conway, Rawlings, & Wolfgram, 2014; Johnson, 2016). This generally lures less qualified applicants to the profession (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). To combat this problem, the No Child Left Behind Act (2002) established minimum qualifications for paraprofessionals by requiring Title I schools to comply with federal restrictions (Nichols, 2013). This included: obtaining a high school diploma, passing a standardized exam, and completing 30 college credits (Nichols, 2013). However, many school systems are forced to hire candidates who do not meet these requirements due to lack of applicants and low job desirability (Appl, 2006). Additionally, while several studies have alluded to the need for extensive experience and education for paraprofessional success (French, 2003; Picket & Gerlack, 2003), other findings revealed paraprofessional supports can be beneficial despite their level of education or prior experience (Jones & Bender, 1993; Giangreco et al., 2001). Regardless of these conflicting findings, paraprofessionals of all skill and experience levels often leave the profession due to low job fulfillment (Giangreco, Doyle, & Suter, 2012).

Job fulfillment. The majority of paraprofessional research occurs in the area of job fulfillment. In a survey of 19 paraprofessionals, Brown and Stanton-Chapman (2014) discovered that the majority of paraprofessionals did not feel they were fairly compensated for their work, had no opportunities for advancement, and had limited job contentment (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). Moreover, it is well documented that paraprofessionals often receive minimal pay (Conway, Rawlings, & Wolfgram, 2014; Johnson, 2016; Katsiyannis, 2000). In addition to monetary compensation, professional fulfillment is often influenced by classroom roles and obligations and varies among paraprofessionals in different settings (Giangreco, Doyle, & Suter, 2012). Specifically, paraprofessionals feel they are required to take on too many tasks (e.g., leading small groups, planning lessons, enforcing rules and procedures) leaving them unsatisfied with their job (Broer, Doyle, & Giangreco, 2005; Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014).

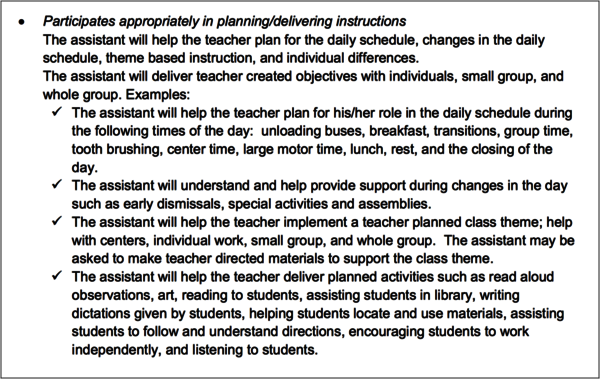

Classroom roles and obligations. Paraprofessional tasks and classroom obligations can drastically vary based on geographical location. While some classrooms and school systems require paraprofessionals to lesson plan, to help with curriculum development, and to assist with behavioral issues, others use paraprofessionals in a supplemental role to ‘aid’ the teacher in the classroom (Appl, 2006; Broer, Doyle, & Giangreco, 2005). In many instances, the classroom teacher is responsible for delegating specific roles and obligations (Appl, 2006; Giangreco, Smith, & Pickney, 2006). In other cases, paraprofessional obligations are vague and unsupervised (Giangreco, Smith, & Pickney, 2006). One study found that almost 70 percent of paraprofessionals in special education inclusive classrooms reported they made decisions without asking the lead teacher for advice (Giangreco & Broer, 2005). These ambiguous job descriptions and unclear roles make it difficult to adequately train, coach, and prepare all paraprofessionals similarly (Armstrong, 2010).

Job preparation and coaching.With regards to job preparation and coaching, several studies found paraprofessionals receive little training on a variety of classroom responsibilities (Armstrong, 2010; Tarry & Cox, 2013). Teachers and paraprofessionals often feel unprepared for some of the academic and social demands of working with students (Armstrong, 2010). This is especially evident for paraprofessionals who work with children with disabilities (Allen & Ashbaker, 2004). Research suggests that there are benefits to providing training and coaching opportunities to paraprofessionals (Jones et al., 2012). Specifically, several single subject studies provide evidence that adequately trained paraprofessionals have a positive impact on classroom relationships (Rueda & Monzo, 2002) and student engagement (Abbot & Sanders, 2012). However, training does not always happen. Brown and Stanton-Chapman (2014) found that the majority of paraprofessionals did not receive adequate classroom training with more than half of the paraprofessionals reporting they received no training within the last year. This lack of preparation can cause discontentment in the classroom and impact classroom relationships.

Relationships with teachers and students. Research recognizes paraprofessional relationships as critical to the overall classroom environment (Blalock, 1991; Downing, Ryndak & Clark, 2000). Paraprofessionals work intimately with teachers, administrators, students and their families, often forming close relationships with all parties (Blalock, 1991; Burgess & Mayes, 2009). The nature of these relationships is often affected by paraprofessionals’ perceived appreciation and job satisfaction. Brown and Stanton-Chapman (2014) found this to be true in their recent study of paraprofessional perspectives. Specifically, when paraprofessionals were asked if their classroom teacher made clear expectations for them, 21 percent (n=4) strongly agreed, 37 percent (n=7) agreed, 26 percent (n=5) disagreed, and 16 percent strongly disagreed (n-3). Theoretically, research dating back to 1985 has indicated the critical need for teachers and paraprofessionals to work as a team, thus confirming the importance of positive classroom relationships (Bennett, Deluca, & Bruns, 1997; Downing, Ryndak, & Clark, 2000; Lacattiva, 1985).

Multiple Perspectives

With each of these key areas taken into consideration, a recent systematic review of paraprofessional relationships with teachers, students, and families revealed only 10 out of 28 studies (36%) explored more than one perspective in a study—that is, studies either focused on one particular issue or on the views of teachers, paraprofessionals, and students individually (Brown, 2016). This means 18 of the 28 (62 percent) studies reported one-sided interpretations and understandings of paraprofessional interactions and did not get reports from both sides about classroom issues. Specific to teacher and paraprofessional relationships, sixteen total studies were retrieved and only two (Chopra & French, 2004; Giangreco, Smith, & Pickney, 2006) reported perspectives from the teacher and paraprofessional (Brown, 2016). Instead, fourteen studies relied solely on the relationship perspective from the paraprofessional and did not include confirming or conflicting views from the teachers. This omission is important because researchers could not compare reports from both sides to corroborate or refute paraprofessional statements.

Of the two studies that looked at both teacher and paraprofessional views, Giangreco, Smith, & Pickney (2006) found that teachers reported very different ideas of classroom relationships than their paraprofessionals and both indicated these interactions were often strained due to varying expectations, roles, and responsibilities. Chopra & French (2004) looked at paraprofessional and teacher relationships with parents to determine the extent of communication involved with both parties. Findings revealed that paraprofessionals and teachers viewed communication with parents very differently, and teachers interacted less frequently but in a much more professional, and less personal, context than paraprofessionals (Chopra & French, 2004).

Overall, limited research involved sustained time in the field with the purposes of exploring the nuanced relationships between teachers and paraprofessional and what this looks like in classroom settings (Armstrong, 2010). Very few studies utilized methodology that allowed researchers to explore relationships over a sustained period of time in order to make assertions about teacher and paraprofessional dealings (Armstrong, 2010; Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). An in-depth exploration of the perspectives on the paraprofessional and teacher relationship from the viewpoints of both paraprofessional and teacher is missing from the literature and can offer useful insight into how administrators and teachers can best support the hiring, training, support, and retention of paraprofessionals (Lewis, 2004).

Current Study

The current study extends a study conducted by Brown and Stanton-Chapman (2014) by using a qualitative case study design to examine the relationship between paraprofessionals’ perspectives of skills, job responsibilities, training, relationships, and satisfaction and teachers’ perspectives of these same ideas. Findings from the Brown and Stanton-Chapman (2014) study indicate there is a difference between paraprofessional and teacher perspectives, but the study did not investigate these views for a sustained amount of time (more than 20 hours). The current study addresses this by thoroughly exploring compounding views of teacher and paraprofessional jobs. Most importantly, it will also fill a gap in the research by comparing multiple perspectives, on the five key areas of paraprofessional research, from teachers and paraprofessionals. The following research questions were addressed:

- What are the skills, experiences, training, and responsibilities of paraprofessionals and teachers, and how does this impact job satisfaction and classroom relationships?

- To what extent are these interpretations shared, or not shared, across teachers and paraprofessionals?

- How do paraprofessionals relate to themselves, classroom teachers, students, and the school community, in narrative re-tellings and through structured observations?

Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

The present study is informed by both narrative theory (Gibson, 1996) and symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1986). The interviews arise from narrative theory, or the understanding that humans are rational beings and find meanings in their stories (Andrews, Squire, & Tambokou, 2008; Trahar, 2013). Narratives are a way for persons to make meaning of their unique experiences. In research, this allows for methodical examination of the construction of a participants’ stories and responses. In this study, paraprofessional and teacher narratives about their experiences will provide insight into how they make meaning of their respective roles with regards to five key themes: a) skill and expertise, b) job fulfillment and satisfaction, c) classroom roles and obligations, d) job preparation and coaching, and e) overall classroom relationships.

In addition to narrative theory, the study is framed by the theory of symbolic interactionism, which serves as a purposeful lens to examine paraprofessional and teacher identity as well as the formation of interactions among these groups (Blumer, 1986). Symbolic interactionism relies on three premises: (1) human beings use meanings they make to act upon certain occurrences or objects, (2) these meanings arise from the social interactions humans have with one another, and (3) these meanings are handled in an interpretive process “used by the person in dealing with the things he encounters” (Blumer, 1969, p. 2). A major component of symbolic interactionism emphasizes that human actions result from their individual interpretation of objects and proceedings surrounding them (Blumer, 1969). In the case of paraprofessionals and teachers, these parties serve as active agents who interpret their environment and respond and behave accordingly. In this study, symbolic interactionism shaped the researchers understanding of how paraprofessionals and teachers interpreted and made meaning of the five common themes in the literature: skills/experience, job fulfillment, roles and obligations, preparation and coaching, and relationships with teachers and students (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014).

Methods

A qualitative case study design was used to investigate the perspectives of paraprofessionals and teachers on multiple issues including: skills and expertise, preparation and training, job fulfillment, roles and obligations, and overall classroom relationships. The qualitative method was selected because the phenomenon to be reviewed includes complex human interactions between the teachers and paraprofessionals (Peterson & Spencer, 1993). Additionally, Klingner and Boardman (2011) note that many studies in special education do not utilize the correct methods to capture “complicated issues faced in schools” (p. 208). As with all case study research, the goal of this study is to deeply understand the boundaries of the case and the intricacy of the behavior patterns of the bounded system (Stake, 1995). In this instance, the bounded system includes the preschool paraprofessionals and teachers in one school system in a mid-Atlantic state.

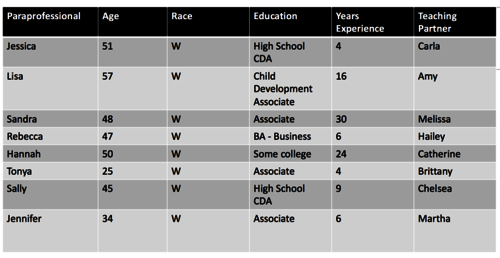

Participants and Context

This study was conducted in eight preschool classrooms across one rural county in Western Virginia. The school district contains 11 elementary schools, three middle schools, and five high schools with a total enrollment of approximately 10,500 students. Ninety-three percent of the school population is White, five percent is Black or African American, and the remaining two percent is comprised of Latino, Asian-American, and American Indian students.

The sample consisted of eight paraprofessionals and the eight teachers they directly worked with. The classroom and participants were selected based on proximity to the researcher’s location and because a previous study was conducted in a neighboring school district (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014).

Table 1

Paraprofessional and Teacher Demographics

Data Sources and Analysis

Data collection concentrated on perspectives of both the teachers and the paraprofessionals who worked directly with them, in their classroom. The objective was to understand both perspectives in order to make assertions and ultimately create overall themes from the settings. In addition to case study methodology, narrative inquiry, as described above, was used to “impose order on the flow of experience to make sense of events and actions” (Riessman, 1993, p. 2). Narrative theory helped the researchers utilize direct conversations and interview transcripts in order to make sense of the observed events and actions. Data were collected through: a) classroom observations; b) semi-structured interviews; and c) document collection.

Classroom observations. A total of 24 classroom observations were conducted (three in each of the eight classrooms). The observations lasted for a total of one hour each, or 24 total hours of observation and were conducted by two researchers in the eight classrooms. Overall, the observations took place over the course of two months and were conducted equally before, during, and after interviews of the participants. During observations, both researchers documented what they saw through detailed field notes in a spiral notebook that were later transcribed. To focus the observations, a detailed observation protocol was established. The researchers also generated post-observation analytic memos that detailed “interpretations, methodological notes, observation notes, theoretical assertions, and high- and low-level inferences” (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014). These analytic memos served to inform the researchers on specific questions or actions to observe the next time they entered a classroom.

According to Schwandt (1997), in qualitative inquiry, reliability “is an epistemic criterion thought to be necessary but not sufficient for establishing the truth of an account or interpretation of a social phenomenon” (p. 137). To establish reliability, Researcher One served as the primary coder and observed in each classroom twice, for a total of 16 hours, and then again in four of the classrooms a third time, for an overall total of 20 hours. Researcher Two, for agreement purposes, observed in four of the eight classrooms twice, for a total of four hours. The two researchers then analyzed the data in order to jointly agree on four common themes or assertions. It is important to note, according to Harris, Pryor, and Adams (2006), these assertions are “general in nature” and reliability comes in the form “that two credible researchers or research teams studying the same or similar contexts will generate consistent overall result patterns, and any variance between result sets will be traceable to documented changes in informants and/or researchers” (p. 9). Additional information on validity criteria are further explained in the data analysis section.

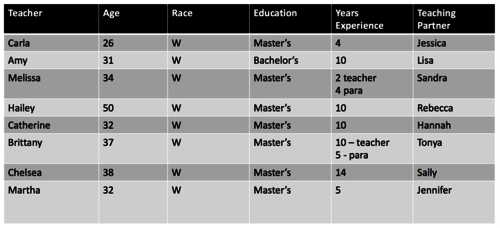

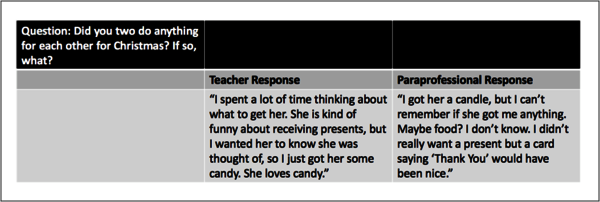

Interviews. After concluding observations, eight paraprofessionals and eight teachers were interviewed with a pre-determined interview protocol informed by themes emerging from observations in conjunction with the five common themes drawn from the extant literature. Researcher One designed two discrete interview protocols (one for the teachers and one for the paraprofessionals) in order to obtain multiple perspectives. Each interview lasted approximately one hour, for a total sixteen hours of interview.

Table 2

Sample Interview Questions

Document collection. Document collection consisted primarily of the school system’s preschool handbook. The handbook is 253 pages and covers all aspects of instruction, responsibilities, relationships within all parties in the preschool program, etc. The handbook specifically covers how to build family partnerships, how to work as a team, procedures for instructional guidance, and necessary forms and other components of the preschool program. In addition to the handbook, several other documents were collected including lesson plans with designated roles and daily instructional notes voluntarily provided by three teachers and four paraprofessionals.

Data Analysis

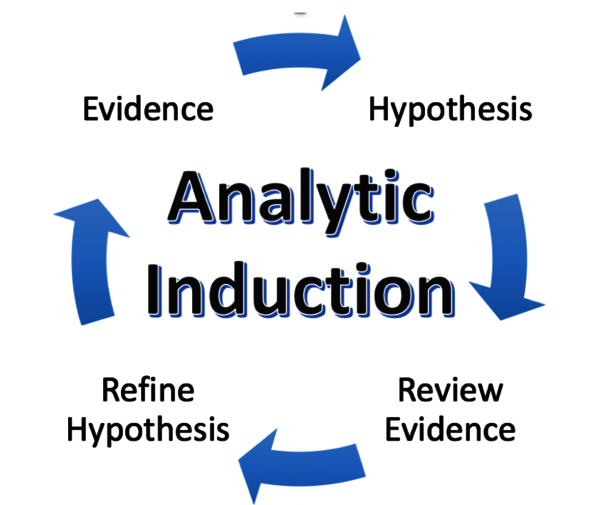

Thesame two researchers who conducted the classroom observations conducted the qualitative data analysis. Researchers used naturalistic and interpretive research to seek out meanings of participants. Expressly, this study aimed to gain an understanding of classroom relationships and interactions that took place in eight preschool settings (Erickson, 1986). The data consisted of observations, field notes, the researcher’s analytic journal, interview transcriptions, and gathered documents. Researchers explored ongoing qualitative data from the interpretivist paradigm and used the method of analytic induction (Erickson, 1986). Specifically, investigators engaged in an iterative and recursive process where data was continually collected, analyzed, and themes were generated from emerging assertions. Analytic induction, in this sense, was used to form systematic evaluations of social phenomena surrounding the paraprofessionals, and teachers, to develop concepts, ideas, and assertions. Quotations from observations, transcribed interviews, and analytic vignettes were used to illustrate the confirmation of events and validate assertions. A reflective journal was kept to provide trustworthiness for the study in what way?(Stake, 2005).

Qualitative analysis used the following five steps, adapted from Erickson (1986) and Znaniecki (1934): (1) Investigators created a definition of a happening and used this to generate an assertion (i.e. Teachers and paraprofessionals share similar classroom responsibilities). (2) Researchers reassessed observations notes, document collection, and interview data to verify or disprove the assertion. (3) If the assertion was not verified, the investigators examined ways to alter the original assertion. (4) Researchers reviewed supplementary interviews, document collections, and observational notes to facilitate adding additional evidence to the new assertion. (5) Ultimately, when an assertion was not substantiated, the investigators found added information to make a new assertion until there were no data unaccounted for. Furthermore, the same two researchers examined the data and assertions to jointly agree on the collective themes. This process, using triangulation, corroborated the evidence from both researchers, all of the data, and established validity (Creswell, 2002; Stake, 2005). After an assertion was confirmed by evidence, it was called a theme.

Figure 1: Analytic Induction from Erickson (1986).This figure represents a visual representation of the analytic induction process.

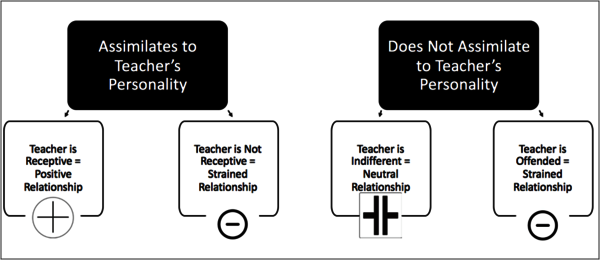

Findings

Findings revealed four themes based on interviews, observations, and document analyses. The themes generated in this study were compiled and presented in relation to topics in prior literature and investigated with multiple perspectives in mind. The four themes highlighted (a) the responsibilities and motivation of paraprofessionals in competition with the receptiveness of teachers, (b) the ways in which paraprofessional behaviors assimilate to mimic teacher behaviors, (c) the mismatch between displayed recognition and appreciation from the teacher, and perceived recognition and appreciation by the paraprofessional, and (d) the governing influence that school, district, and regional policies have on individual classroom outcomes and relationships.

Theme 1: Responsibilities, Motivation, and Receptiveness

Teachers and paraprofessionals share similar classroom responsibilities. There is a direct connection between paraprofessional motivation (willingness to engage in specific tasks) and teacher receptiveness (willingness to relinquish responsibilities to paraprofessionals).

Classroom roles, responsibilities, and interactions are often determined by lead teachers and passed on to paraprofessionals. Lead teachers can either be receptive to help with instruction and classroom interactions or be hesitant to relinquish control. On the other side, paraprofessionals may display strong motivation to become involved in classroom activities, or he or she may require more support and take less initiative. The interchange between these two parties often influences many aspects of the classroom environment.

Table 3

Examples of the Dual-Connection between Paraprofessional (P) Motivation and Teacher (T) Acceptance/Receptiveness

|

|

High P Motivation |

Low P Motivation |

|

High T Receptiveness

|

T says in an interview of P, “The way our system works, she pretty much does everything I do. It’s great and really helpful. The kids treat us the exact same.” (Interview with Teacher 3) |

During center time, T asks P if she wants to help lead an art activity. P responds, “No. I’m not really good with crafts. You know that.” (Observation in Classroom 5) |

|

Low T Receptiveness |

P asks if it is acceptable to begin another story because her group finishes before T’s group. T responds, “You stick to the schedule. Just wait.” (Observation in Classroom 4) |

T becomes agitated in an interview and says of the P, “I don’t want her to do anything because she doesn’t know how to do it anyway. Plus, she’s fine just sitting on her butt, so that’s one thing we agree on.” (Interview with Teacher 1) |

The above table illustrates four examples of the interchange among paraprofessional motivation and teacher receptiveness to responsibilities. As described in Brown and Stanton-Chapman (2014), motivation is defined as a “paraprofessional’s willingness to perform classroom tasks” (p. 6). Receptiveness is defined as “the teacher’s willingness to relinquish control and allow the paraprofessional to complete classroom tasks” (Brown & Stanton-Chapman, 2014, p. 6). In the occurrence of high teacher receptiveness and high paraprofessional motivation, Mrs. Hailey, emphasized the importance of mutual communication and collaboration. “She pretty much does everything I do. It’s great and really helpful,” said Mrs. Hailey. Mrs. Hailey also made a point to illustrate the positive impact this had on the students in the classroom by stating they treated her and her paraprofessional “The exact same.” (Interview, 4/12/16).

An example of the exact opposite of this interchange can be seen in a teacher with low receptiveness and a paraprofessional with low motivation. Mrs. Chelsea became very agitated when discussing her relationship with the paraprofessional. She made multiple comments about how the paraprofessional “Doesn’t know how to do it anyway” and she does not “want her to do anything.” (Interview, 3/22/16). These remarks were reinforced during a separate classroom observation illustrated in the following vignette:

The students return from specials (art today) and enter the room quietly in a single-file line. Sandra leads the line. As everyone arrives, Mrs. Melissa asks the students to sit on the farm-themed carpet. Sandra immediately retreats to chair in the back corner of the room. Mrs. Melissa begins to ask the students what they did in art, how their weekend was, and other introductory morning questions. One student, who is having trouble sitting still, stands up and walks to the back corner of the room which is adjacent to Sandra. Sandra does not acknowledge him but instead picks up a magazine and begins flipping the pages. Mrs. Melissa carries on with her questioning of the children and then notices the stray student. She appears slightly irritated and says, “Steven. Get back to the carpet.” Sandra briefly looks up from her magazine, rolls her eyes, and then continues to read.

Steven retreats to the rug. He places both hands in the air and begins to wave them around. Only two students look at him. Mrs. Melissa keeps reading. Suddenly Steven begins making animal noises. He snorts like a pig several times and uses his index finger to turn up the tip of his nose (seemingly imitating a pig). Mrs. Melissa glances at Sandra. She is still reading her magazine. Steven, continuing to make the pig noise, starts to get the attention of at least five students. Mrs. Melissa politely asks him to, “Please be quiet during story time.” Sandra again briefly looks up from her magazine, smiles, and lets out a small chuckle. (Observation, 2/23/16).

In this vignette, the paraprofessional, Sandra, made no attempt to assist when a student displayed inappropriate or distractive behavior. Similarly, Mrs. Melissa made no attempt to engage Sandra in the classroom activity or ask for her assistance in managing the behavior. This is an observed example of the paraprofessional displaying low motivation while the teacher simultaneously displays low receptiveness to paraprofessional support.