Table of Contents

- Special Education Legal Alert. By Perry A. Zirkel

- Buzz from the Hub

- Use of Visual Performance Feedback to Increase Teacher Use of Behavior-Specific Praise among High School Students with Severe Disabilities. By Michelle L. Simmons, Ed.D., Robin H. Lock, Ph.D., Janna Brendle, Ph.D., and Laurie A. Sharp, Ed.D.

- The Changing Role of the Itinerant Teacher of the Deaf: A Snapshot of Current Teacher Perceptions. By Holly F. Pedersen, Ed.D., Minot State University and Karen L. Anderson, Supporting Success for Children with Hearing Loss

- Book Reviews

- Latest Employment Opportunities Posted on NASET

- Acknowledgements

Special Education Legal Alert

By Perry A. Zirkel

© August 2020

This month’s update concerns issues that were subject to recent court decisions of general significance: (a) transportation under a state open enrollment law, and (b) compensatory education and other relief from stay-put violation.

|

In an officially published decision in Osseo Area SchoolsIndependent School District No. 279 v. M.N.B. (2020), the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals addressed the issue of whether the IDEA requires a school district, upon accepting the application of a nonresident student with disabilities under a state open enrollment law, to provide transportation, as specified in the student’s IEP, to and from school. Based on the parent driving the child and the open enrollment statute’s provision for transportation within district boundaries, the district only reimbursed the parent for the segment of the round trip between the school and the intersection of the district border. Both the hearing officer and the federal district court ruled that under the IDEA the district was responsible for the cost of the full round trip between the home and the school. The district filed an appeal with the Eighth Circuit to challenge their interpretation of the IDEA. |

|

|

One argument for the parent was the lower court’s conclusion that once the district accepted the student’s application, it was responsible for FAPE as documented in the IEP, which included transportation to and from school. |

The Eighth Circuit relied on the Constitution’s spending clause, which the Supreme Court interpreted as requiring Congress, if it intends to impose a condition on the grant of federal moneys, to do so unambiguously. The IDEA lacks such clear notice. |

|

A second argument for the parent that the lower court had accepted was that the parents had filed a state complaint that resulted in a finding against the district’s blanket policy. |

The Eighth Circuit observed that the state complaint decision may have been a mistaken interpretation of state law but in any event lacked any preclusive effect on the court’s IDEA interpretation. |

|

The third argument for the parent is that in Letter to Lutjeharms (1990), OSEP supported her interpretation of the IDEA in relation to a state open enrollment law. |

Pointing out that the OSEP interpretation neither addressed this state law nor the Spending Clause, the Eighth Circuit concluded that this guidance lacked not only a binding but also a persuasive effect. |

|

Finally, the parent cited a Fifth Circuit decision that provided for transportation beyond a district’s borders under certain specified circumstances. |

The Eighth Circuit made short shrift of this argument based on rather distinct factual differences between those circumstances and the open enrollment situation at issue here. |

|

As an officially published federal appellate ruling, this decision carries considerable weight. Nevertheless, it is not binding outside the states of the Eight Circuit and is limited to the specific provisions of the open enrollment law and IEP at issue in the case. |

|

|

In Doe v. East Lyme Board of EducationIII (2020), the Second Circuit Court of Appeals issued its third decision in litigation that dated back to the 2008-09 school year, when under the IEP the parents agreed to pay the tuition at their unilateral placement of their child with autism at a private religious school and the district agreed to pay for specified additional services, including Orton-Gillingham reading instruction, speech therapy, and PT/OT. In Doe I (2015), the Second Circuit ruled that (a) the district’s IEP for 2009-10 was appropriate; (b) despite the district’s failure to propose an IEP in 2010–11, the parent was not entitled to reimbursement because the religious school was not appropriate; (c) the district violated stay-put by not continuing to pay for the additional services in the 2008-09 IEP, and (d) the district had to not only reimburse the parent for the out-of-pocket costs ($97K) but also, via a compensatory education award, the remainder of services that the parent was not able to arrange. In Doe II, the Second Circuit dismissed the parents’ appeal because the district court had not yet finalized its calculations of the reimbursement and compensatory education. After the lower court ordered the district to pay $48K plus interest in additional reimbursement and put an additional $192K in an escrow account for compensatory education, the parent challenged various aspects of this stay-put remedy. |

|

|

Her first challenge was these aspects of the compensatory education award: the escrow account, the escrow agent, and the six-year time limit. |

The Second Circuit summarily rejected these claims, pointing out that the parent had requested an escrow arrangement, this specific escrow agent, and the specified six-year time limit. |

|

Second, she challenged the district court empowering the escrow agent to not only review her claims from the account but also reduce the amount if the student no longer needed the services. |

The Second Circuit upheld this challenge based on the principle that compensatory education is not subject to delegation beyond the final authority of impartial adjudication. |

|

She also challenged the district court’s order that she pay half of the escrow agent’s administrative fee. |

The Second Circuit agreed, reasoning that the district was responsible for FAPE, which must be “free” to the parent. |

|

Next, she challenged the district court’s interest calculation. |

The Second Circuit roundly rejected this challenge. |

|

Undeterred, she also challenged the original appropriateness rulings for 2009-10 and 2010-11. |

The Second Circuit easily denied these challenges as decided by Doe I and unaffected by Endrew F. |

|

Finally, she sought (a) further reimbursement, (b) expert witness fees, and (c) attorneys’ fees. |

The Second Circuit respectively ruled (a) no abuse of discretion, (b) no entitlement, and (c) improper appeal. |

|

One cannot help but wonder at the transaction costs of litigation, including 12 years of time (with the “child” now in college) and hundreds of thousands of dollars for a stay-put violation (after a complete rejection of the original FAPE reimbursement claim), and the corresponding loss of perspective of this parent (who after Doe I proceeded without legal counsel). |

|

Buzz from the Hub

All articles below can be accessed through the following links:

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-august2020-issue1/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-july2020-issue1/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-june2020-issue2/

Planning for Equity and Inclusion: A Guide to Reopening Schools

COVID-19 has changed public education in dramatic ways, and the 2020–2021 school year is posing even more challenges. This short guide shares specific ways school and district leaders can prioritize equity and inclusion as they rethink their approach to public education in the COVID-19 world.

Building Engagement with Distance Learning

This resource is part of an ongoing series produced by the OSEP-funded TIES Center. It provides a framework for supporting all students, including those with significant cognitive disabilities. The series explores important considerations in providing distance learning, such as daily meetings, behavioral supports, individualizing supports for students, data collection, and embedding instruction at home.

A Guide to Equity in Remote Learning

This guide emerges from the ongoing webinar series Advancing Equity in an Era of Crisis, a collaborative effort of several professional organizations in California (e.g., California Association of African-American Superintendents and Administrators). The 63-page guide examines how California can equitably meet the needs of all students when it resumes instruction in the 2020-21 school year, whether in classrooms, remotely, or a hybrid of both. Much food for thought here, even if California isn’t where you live.

Testing for COVID-19: What’s Your State’s Plan?

The Department of Health and Human Services has posted the COVID testing plans (July through December) from all states, territories, and localities. The plans include details on responding to surges in cases and reaching vulnerable populations.

Talking to Very Young Children about Race

This 4-page resource is subtitled “It’s necessary now, more than ever.” Why? Because children see injustices on the news, at the store, on the playground, and in their classrooms. It is important for adults to explain to them what is going on in a way that makes sense based on their developmental level. These conversations need to become a pattern during the early childhood years and not a single event. Excellent, subtle suggestions are given. From the National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations.

Anti-Racism Resource Directory for Families: Resources for Multiple Grade Levels

Parents may not know where to start with discussions of race, racial justice, and anti-racism with their children. Or perhaps they’ve already had family conversations and are looking to continue the discussion or explore action. This Learning Heroes directory assists families as they navigate the many free resources that are available.

The Ultimate Parents’ Guide to Summer Activity Resources

To give parents a sense of the summertime fun can be had, the Washington Post compiled resources in 10 categories: reading, education, travel, mental wellness, music, art, physical activity, theater and dance, languages, and entertainment.

Parent Advocacy Toolkit for Equity in Use of COVID-19 Funds

NCLD and 13 partner organizations released recommendations to guide how the use of funding can prioritize equity and ensure our most vulnerable students receive the greatest support. Based on these recommendations, NCLD also created a 12-page toolkit to help parents advocate for equity as school districts develop reopening plans for the 2020-2021 school year.

COVID-19 Planning Considerations: Guidance for School Re-entry

This guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics supports education, public health, local leadership, and pediatricians collaborating with schools in creating policies for school re-entry that foster the overall health of children, adolescents, staff, and communities and are based on available evidence.

Special Report | How We Go Back to School

To reopen schools in the fall, K-12 leaders must balance three critical, often competing responsibilities: the health and safety of their people, the role their schools play in the larger community, and the effective teaching of their students. To help district and school leaders navigate these monumental decisions, Education Week lays out the big challenges ahead and some solutions in an 8-part series.

Spanish-Language Webinar on the Transition to Kindergarten Amid COVID-19

The transition into kindergarten marks a major milestone in a child’s life. The ED-funded Early Learning Network presents this 33-minute webinar specifically designed for Spanish speaking families to help families prepare their child for a successful transition into kindergarten during the pandemic.

The National Responsible Fatherhood Clearinghouse

Funded by HHS, this clearinghouse disseminates current research and innovative strategies to encourage and strengthen fathers and families. Many resources are also available in Spanish.

What’s Important to Native Youth?

Do you know? Find out in the infographic and brief developed to summarize the findings of a survey of Native youth and what they had to say. It will certainly inform your outreach to and work with youth.

Reinforcing Resilience: How Parent Centers Can Support American Indian and Alaska Native Parents

Considering the traumas that indigenous peoples have survived all these years and the current challenges they face, resilience is an essential quality to have. Here’s how Parent Centers can add value and vigor to an essence that has historically been integral in Native life.

Bouncing Back from Setbacks: A Message for American Indian and Alaska Native Youth

This brief is written directly to Native youth, as if it were a letter coming from the local Parent Center. It highlights 10 skills known to be builders of resilience in youth. Also available online in HTML.

We hope you enjoy the multicultural journey that all of the resources in Working with Native Children and Youth will take you on!

Will Your Schools Re-Open? What’s the Plan, Stan?

Johns Hopkins University has launched a new tracker that analyzes school reopening plans across the country. The tool examines whether or not each state reopening plan addresses a dozen different issues. You can also download state plans directly from the tracker. How timely, eh?

2020 Determination Letters on State Implementation of IDEA

How well are the states and territories implementing IDEA? The 2020 determination letters will tell you. (Can you guess who received the “needs intervention” determination for the ninth year in a row?!)

Comparison Guide: Video Conferencing Tools for Your Nonprofit

As nonprofits continue to do their work remotely, the need for a solid video conferencing tool has never been greater. TechSoup created this at-a-glance guide to help nonprofits make informed decisions about choosing what’s right for their organization.

Tech Soup Courses for Free!

TechSoup has also created a free track of courses to provide information and tools as nonprofits scale up the work they do remotely, including having necessary tech tools, how to boost collaboration, and how to ensure information security.

Camp Kinda

(In English and Spanish) | Here’s a free, virtual summer camp experience designed to keep kids engaged, asking questions, and having fun even while they’re stuck at home. “Open” each weekday starting June 1 to September 1. On any given day, kids may be exploring the art of graphic novels, unlocking the mysteries of history, or jumping into the world’s craziest sports. Also available in Spanish.

How to Support Your Unique, Quirky Child

(In English and Spanish) | When your child behaves differently from others, it’s endearing—but is it OK? Read this Great Schools article to find ways to celebrate your child’s unique nature. A version in Spanish is also available: Cómo apoyar las características únicas de tu hijo.

Video | The CDC Guidance on Reopening Schools, Explained

CDC recently released guidance on reopening schools. Its recommendations, which are voluntary, give parents and teachers their first detailed glimpse of how schools might change their operations to contain COVID-19. How much these recommendations will influence schools’ operations depends on the decisions of state and local leaders. Watch Education Week’s 4-minute video for an explanation of several key points.

SAVE the DATE | Webinar on Monday, June 8th @ 3 pm EDT

Safeguarding Back to School: Principles to Guide a Healthy Opening to Classrooms During COVID-19

The transition back to school this year will be unlike any in history. How do we safely reopen? In this edWebinar, leaders of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and Brooklyn Laboratory Charter Schools will discuss key questions we must all consider as we begin the journey back to school–from the school bus ride to the dismissal bell. Register here. If you’d like to receive an email with a link to the recording afterwards, add your name to the list at: https://forms.gle/V6mgSp8n8fqxjv318

Use of Visual Performance Feedback to Increase Teacher Use of Behavior-Specific Praise among High School Students with Severe Disabilities

Michelle L. Simmons, Ed.D.

Robin H. Lock, Ph.D.

Janna Brendle, Ph.D.

Laurie A. Sharp, Ed.D.

Abstract

Behavior-specific praise has been deemed an effective, evidence-based positive behavioral intervention and support practice for use among high school students with severe intellectual disabilities. However, teachers are not adequately trained to use such practices with fidelity. One way to address this shortcoming is by implementing a performance feedback approach characterized with observations and consultations that provide visual performance feedback. Using a changing criterion research design, the present study evaluated the effect of a performance feedback approach to increase a high school teacher’s use of behavior-specific praise among students with severe disabilities. Results showed significant increases with the teacher-participant’s use of behavior-specific praise and mixed trends with the student-participants’ exhibition of challenging and replacement behaviors. A discussion of reported results was provided, along with implications for stakeholders in teacher preparation programs and high school contexts. Limitations and areas for future research were also addressed.

Keywords: behavior-specific praise, severe intellectual disabilities, high school students, challenging behaviors, replacement behaviors

Introduction

Students with severe intellectual disabilities have chronic and severe deficits in both adaptive behavior and cognitive functioning that manifest during early childhood and are likely to continue for life (Handleman, 1986). These deficits often lead to a range of challenging behaviors that significantly impede a student’s ability to exhibit appropriate social functioning in school-based settings (Lane & Wehby, 2002; Medeiros, 2015). Challenging behaviors include noncompliance, stereotypy (e.g., intense fixations on objects or parts of objects, impulsivity, repetitive behavior patterns), and self-injury. Without appropriate interventions, challenging behaviors can interfere with how students with severe intellectual disabilities interact with others (Carter, Sisco, Chung, & Stanton-Chapman, 2010; Matsushima & Kato, 2015; Nijs & Maes, 2014) and have an impact on the academic learning environment (Räty, Kontu, & Pirttimaa, 2016). Thus, teachers who work among students with severe intellectual disabilities must use teaching strategies that emphasize curricular content and self-help skills, while also reducing any challenging behaviors that impede the acquisition of critical academic and functional skills (Handleman, 1986).

Beginning in the 1960s, researchers have utilized applied behavior analysis as a systematic way to study individual functions of human behavior in an attempt to “reduce the frequency and severity of challenging behaviors and facilitate the acquisition of adaptive skills” (Dixon, Vogel, & Tarbox, 2012, p. 7). Initial theories posited that challenging behaviors could be managed by automatic reinforcement (Vaughan & Michael, 1982; Vollmer, 1994), positive reinforcement (Carr, 1977), and negative reinforcement (Carr, Newsom, & Binkoff, 1976; Iwata, 1987). Almost 20 years later, these theories became the foundation for functional analysis (Dixon et al., 2012), which provided a methodology to assess multiple behaviors and functions during a single experimental investigation in order to develop effective interventions for individuals who exhibit challenging behaviors (Hanley, Iwata, & McCord, 2003; Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982; Iwata et al., 2000). To date, federal legislation has mandated that schools use functional analysis in the form of functional behavioral assessments (FBA) when a student’s behavior impedes the learning process (Drasgow, Yell, Bradley, & Shriner, 1999; Zirkel, 2017). One of the goals of FBA is to determine the purpose of a student’s challenging behavior, identify environmental factors surrounding challenging behaviors and implement positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) to promote alternate, replacement behaviors (Farmer, Lane, Lee, Hamm, & Lambert, 2012).

Behavior-specific praise has been deemed an effective, evidence-based PBIS practice for use among high school students (Duchaine, Jolivette, & Fredrick, 2011; Kennedy, Hirsch, Rodgers, Bruce, & Lloyd, 2017). Teachers should deliver behavior-specific praise to immediately reinforce a student’s desired behavior with a descriptive verbal statement. Unfortunately, teachers are not adequately prepared or trained to use PBIS practices with fidelity (Kennedy et al., 2017), particularly among high school students with severe intellectual disabilities (Bruhn et al., 2016). Stormont and Reinke (2014) recommended using a data-based performance feedback approach to address this need. Through this approach, a trained behaviorist serves as an instructional coach to the classroom teacher and conducts systematic, direct observations of the teacher in the classroom setting where the challenging behaviors occur. The instructional coach collects observational data and facilitates subsequent consultations with the teacher to share visual performance feedback by reviewing a graph that depicts the classroom teacher’s use of PBIS practices.

Available studies that examined the use of visual performance feedback to enhance teacher performance with PBIS practices primarily focused upon young children and adolescents in the elementary and middle school grade levels (Allday et al., 2012; Fabiano, Reddy, & Dudek, 2018; Gage, Grasley-Boy, & MacSuga-Gage, 2018; Gage, MacSuga-Gage, & Crews, 2017; Mesa, Lewis-Palmer, & Reinke, 2005; Reinke, Lewis-Palmer, & Merrell, 2008; Sweigart, Landrum, & Pennington, 2015). There were a limited number of studies that specifically focused on teacher performance with PBIS practices among older adolescents in the high school grade levels (Bruhn et al., 2016; Hawkins & Heflin, 2011; Kalis, Vannest, & Parker, 2007). The purpose of the present study was to address this research gap and evaluate the effect of visual performance feedback on the frequency of (a) behavior-specific praise statements given by a high school special education teacher and (b) challenging and replacement behaviors exhibited by high school students with severe intellectual disabilities.

Methods

Participants

Information provided about participants relates to the time that the present study was conducted. There was one teacher-participant, Ms. George (all names are pseudonyms). Ms. George was a high school special education math and science life skills teacher with more than 10 years of teaching experiences in special education settings. There were also three student-participants who were high school students that met IDEA eligibility criteria for a severe intellectual disability. Kara was a Caucasian female classified as a sophomore-level student, Chris was a Caucasian male classified as a junior-level student, and Cody was a Caucasian male classified as a senior-level student. The identified adaptive behavior deficits for Kara, Chris, and Cody were of such significance that their access to the general education instructional environment and daily functioning were severely limited. Therefore, Kara, Chris, and Cody received instruction for more than 80% of the school day in a self-contained life skills classroom, as well as frequent monitoring and supervision during meal times, transition periods, and toileting.

Role of Researchers

Two individuals collected data for the present study. Both of these individuals had previously received specialized training in behavior management techniques. The first individual was the primary researcher for the present study (i.e., the first author) and was a direct observer who completed study session observations, recorded data measurements, facilitated consultations with the teacher-participant, and performed all data analyses. The second individual was a Licensed Specialist in School Psychology (LSSP) employed by the school district and assigned to the high school campus where the present study was conducted. The second individual served as an inter-observer who completed observations and recorded data measurements with the primary researcher during the intervention phase. Other members of the research team (i.e., the second, third, and fourth authors) contributed expertise once data analyses were completed.

Setting

The present study was conducted in a public high school located in a rural area of the South Central United States that served students in grades 9-12. The high school had a student enrollment of approximately 1,500 students who resided in several surrounding rural communities. The high school used a self-contained model for the life skills classroom, which was led by a state-certified special education teacher. One teaching assistant was also assigned to the life skills classroom and provided the teacher and students with additional support during the school day.

At any given time throughout the school day, there were typically six to eight students in the life skills classroom. The life skills classroom used a paired classroom seating arrangement with two individual student desks facing one another. A large electronic display was affixed to a wall at the front of the classroom. For the majority of observed instructional delivery, Ms. George used the electronic display, along with an iPad. Additionally, Ms. George was unaware of who the student-participants were and knew them as Student 1 (i.e., Kara), Student 2 (i.e., Chris), and Student 3 (i.e., Cody).

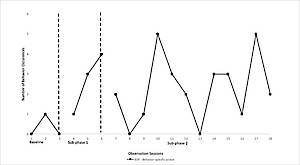

Research Design

The present study employed a changing criterion research design. This research design is a variant of the multiple-baseline research design and characterized by two major phases (Hartmann & Hall, 1976). The first phase, the baseline phase, includes initial observations for a single target behavior. The second phase, the intervention phase, implements a treatment for the target behavior in a series of sub-phases. During the first intervention sub-phase, an interim criterion for desired level of performance is established (Johnson & Christensen, 2014). Once the interim criterion is achieved, it is gradually increased to establish a functional relationship between behaviors and the treatment continues. Successive intervention sub-phases continue incremental criterion progression and intervention delivery throughout the duration of the study.

The goal of the present study was to increase Ms. George’s use of behavior-specific praise (i.e., the independent variable) with challenging and replacement behaviors (i.e., the dependent variables) exhibited among Kara, Chris, and Cody. To achieve this goal, the treatment delivery included weekly visual performance feedback consultations between the teacher-participant and primary researcher after each intervention sub-phase. Following baseline phase observations, interim criterion calculations for intervention sub-phases were made using frequency counts of the independent variable. It was determined that the mean rate of behavior-specific praise for each intervention sub-phase must be greater than or equal to the mean of the baseline phase plus the mean of the preceding intervention sub-phase.

Materials

An event recording data collection sheet was used to record the frequency of independent and dependent variables during intervention sub-phases for Kara, Chris, and Cody (Alberto & Troutman, 2009). The event recording data collection sheet was a table consisting of four blank rows and five columns with the following labels: Date of Observation, Time Start, Time Stop, Notation of Occurrence, and Total Frequency of Occurrence. From this data, graphic displays were created to visually depict trends in Ms. George’s levels of delivery of behavior-specific praise during baseline and intervention sub-phase observations for Kara, Chris, and Cody (Johnson & Christensen, 2014).

Procedure

The present study was conducted during a six-week time frame that implemented procedures for five different conditions that occurred during the baseline and intervention phases. These conditions were: (1) baseline phase observations, (2) teacher consultations, (3) intervention sub-phase observations, (4) inter-observer agreement checks, and (5) social validity questionnaires. Following is a detailed description of the specific procedures and conditions for each phase.

Baseline phase. Baseline phase observations were conducted during the first week to determine the frequency of behavior-specific praise offered by Ms. George, as well as the frequency of challenging and replacement behaviors exhibited by Kara, Chris, and Cody. For each student-participant, the primary researcher completed three separate 20-minute observation sessions and used event recording data sheets to notate the frequency of occurrence of independent and dependent variables. An audio recording of each baseline observation session was made, and the primary researcher kept anecdotal notes in a journal. During baseline phase observation sessions, no changes were made to the environment and no treatment was applied.

Intervention phase. On the Monday of the second week, the primary researcher conducted a 20-minute initial teacher consultation with Ms. George to provide visual performance feedback. Visual performance feedback consisted of the following instructional coaching strategies. The primary researcher noted and reinforced specific examples of Ms. George’s behavior specific praise delivery using graphic displays. The primary researcher also identified and discussed occurrences when Ms. George used non-specific praise, reprimands, or other non-PBIS responses toward student behaviors. During these occurrences, the primary researcher encouraged Ms. George to provide examples of PBIS strategies that could have been used with students instead of the aforelisted behavioral approaches. In addition, the primary researcher delivered a brief training on behavior-specific praise to Ms. George. This training included an overview of evidence-based practices, examples of behavior-specific statements (see Table 1), and opportunities for Ms. George to practice using behavior-specific praise. At the conclusion of the initial teacher consultation, the primary researcher communicated the mean rate of behavior-specific praise from baseline observation sessions for Kara, Chris, and Cody to Ms. George.

Table 1

Examples of Behavior-specific Praise Statements

|

Observed Behavior |

Behavior-specific Praise Statements |

|

Kara verbally responds to a question posed during class. |

“Way to go, Kara! Thank you for giving an answer to that question.” |

|

Cody gets his blue binder out to begin an assignment. |

“Good job! Thank you for getting your binder out, Cody!” |

|

Chris remains in his seat and raises his hand to get the teacher’s attention. |

“I like that you raised your hand to get my attention, Chris.” |

|

Chris sits quietly while the teacher gives instructions. |

“Chris, I noticed you listened while I was giving instructions for that assignment. Well done!” |

|

Cody refrains from hand movements or gestures that create inappropriate noise. |

“Wow, thank you for keeping your hands quiet, Cody! You made it easy for your classmates and me to hear!” |

|

Kara states, “Ms. George” to request help from the teacher. |

“Thank you, Kara, for using my name to get my attention. That was helpful!” |

Following the initial teacher consultation, the primary researcher and inter-observer conducted joint intervention sub-phase observations of Kara for three weeks and Chris and Cody for five weeks. Each week, the primary researcher and inter-observer conducted three 20-minute observation sessions of each student-participant simultaneously, yet independently of one another. The primary researcher and inter-observer used event recording data sheets to record data, kept anecdotal notes in a journal, and made audio recordings of each observation session. After each observation session, inter-observer agreement checks were made by calculating a Cohen’s Kappa statistic (Bryington, Palmer, & Watkins, 2002). For each variable, the number of agreements was divided by the number of agreements plus disagreements. Resulting Kappa values were interpreted as poor (below 0.40), fair (between 0.40 and 0.59), good (between 0.60 and 0.74), and excellent (between 0.75 and 1.00). As shown in Table 2, the majority of Kappa values reflected good inter-observer agreement with independent and dependent variables (K = 0.67), although there were two instances that showed poor inter-observer agreement (K = 0.33).

Table 2

Kappa Values for Inter-Observer Agreement Checks

|

|

Behavior-specific Praise |

Challenging Behaviors |

Replacement Behaviors |

|

Kara |

.67 |

.33 |

.67 |

|

Chris |

.67 |

.67 |

.67 |

|

Cody |

.67 |

.67 |

.33 |

Every Monday, the primary researcher held a 20-minute teacher consultation with Ms. George regarding the previous week of intervention sub-phase observations. During teacher consultations, the primary researcher provided visual performance feedback and facilitated dialogue concerning Ms. George’s use of behavior-specific praise with Kara, Chris, and Cody. The primary researcher concluded each teacher consultation by sharing information related to expected levels of behavior-specific praise for the forthcoming week. Once intervention sub-phase observations concluded, Ms. George completed separate social validity questionnaires for Kara, Cody, and Chris. The social validity questionnaire consisted of 13 Likert-type statements for which Ms. George used a five-point scale (i.e., 5 = Strongly Agree, 4 = Agree, 3 = Uncertain, 2 = Disagree, 1 = Strongly Disagree) to rate her personal viewpoints toward behavior-specific praise (see Figure 1).

Although Ms. George completed a social validity questionnaire for Kara, Chris, and Cody separately, her ratings for each statement were identical. Ms. George gave the highest rating (i.e., Strongly Agree) to every questionnaire statement except Statement 4 and Statement 8 (see Figure 1). For these two questionnaire statements, Ms. George gave the second-highest rating (i.e., Agree).

|

Figure 1.Likert-type statements included on social validity questionnaire. |

Results

Analyses of baseline phase observations revealed a variety of challenging behaviors exhibited by Kara, Chris, and Cody. Kara frequently uttered inappropriate words or sounds and used gestures to gain the attention of the teacher or a peer. Inappropriate utterances included giggling, making kissing noises, excessive audible yawning, and yelling off-topic words. Kara would also touch Ms. George’s arm, wave a piece of paper in the air, or stand up while Ms. George was talking. Chris often yelled inappropriately, repeated or mimicked Ms. George’s words, or shouted off-topic words or phrases. Chris would also create loud sounds using random objects and by slamming his hands on surfaces, such as desktops and the floor. Cody regularly uttered inappropriate words or sounds, snorted, yelled off-topic responses out of turn, or used random objects to create drumming sounds. Cody would also continually enter Ms. George’s personal space, lay his head on her shoulders or arms, or wave objects in her face.

Analyses of baseline observations for Ms. George revealed that she typically responded to challenging behaviors by avoiding eye contact with the student, ignoring the behavior, issuing a verbal correction or reprimand, stating the student’s name, or taking away sound-making objects. There were two occurrences where Ms. George provided verbal praise for replacement behaviors. However, the praise she provided was generic and not specific to the desired behavior (i.e., “good job,” “thank you”).

Independent Variable Data

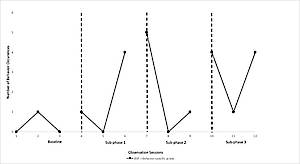

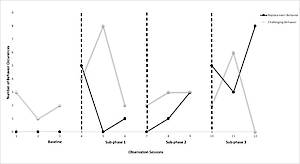

The number of behavior-specific praise statements given by Ms. George to Kara, Chris, and Cody are shown in Figures 2, 3, and 4, respectively. With Kara, the mean rate of behavior-specific praise during the baseline phase was 0.3 and had increased to 1.6 after the first intervention sub-phase (see Figure 2). This increasing trend continued through the second (2.0) and third (3.0) intervention sub-phases and exceeded the established interim criterion for both sub-phases (1.9 and 2.3, respectively).

|

Figure 2. Number of behavior-specific praise statements given by Ms. George to Kara |

With Chris, the mean rate of behavior-specific praise during the baseline phase was zero and increased to 3.6 after the first intervention sub-phase (see Figure 3). During the second intervention sub-phase, the mean rate of behavior-specific praise decreased to 1.9 and failed to meet the established interim criterion of 3.6. The mean of behavior-specific praise continued to be calculated for subsequent sub-phase observations during the next three weeks and reflected the same trend.

|

Figure 3. Number of behavior-specific praise statements given by Ms. George to Chris |

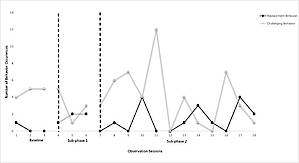

With Cody, the mean rate of behavior-specific praise during the baseline phase was 0.3 and increased to 2.6 after the first intervention sub-phase (see Figure 4). During the second intervention sub-phase, the mean rate of behavior-specific praise decreased to 2.5 and failed to meet the established interim criterion of 2.9. Similar to Chris, the mean rate of behavior-specific praise given to Cody continued to be calculated for subsequent sub-phase observations during the next three weeks and reflected the same trend.

Figure 4. Number of behavior-specific praise statements given by Ms. George to Cody

Dependent Variable Data

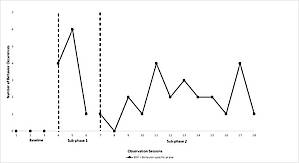

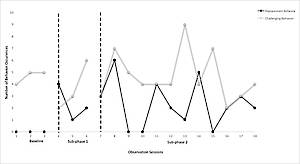

The number of challenging and replacement behaviors exhibited by Kara, Chris, and Cody are shown in Figures 5, 6, and 7, respectively. With Kara, the mean rates for challenging behaviors was 2.0 and zero for replacement behaviors during the baseline phase (see Figure 5). During the first intervention sub-phase, there were increases in the mean rates of Kara’s challenging (4.7) and replacement (3.0) behaviors. However, this trend was reversed during the second intervention sub-phase (challenging behaviors = 2.6, replacement behaviors = 1.3). During the third intervention sub-phase, the mean rate of Kara’s challenging behaviors remained the same, yet increased dramatically for her replacement behaviors (5.3).

|

Figure 5. Number of challenging and replacement behaviors exhibited by Kara |

With Chris, the mean rates for challenging behaviors was 4.6 and zero for replacement behaviors during the baseline phase (see Figure 6). The mean rates for Chris’s challenging behaviors decreased to 3.3 during the first intervention sub-phase and then increased back to 4.6 during the second intervention sub-phase. Data also revealed that Chris’s replacement behaviors increased to 2.3 during the first intervention sub-phase with no change during the second intervention sub-phase.

With Cody, the mean rates for challenging behaviors was 4.6 and 0.3 for replacement behaviors during the baseline phase (see Figure 7). The mean rates for Cody’s challenging behaviors decreased to 3.6 during the first intervention sub-phase and then increased back to 4.2 during the second intervention sub-phase. Data also revealed that Cody’s replacement behaviors increased to 1.6 during the first intervention sub-phase and then decreased slightly to 1.3 during the second intervention sub-phase.

|

|

|

Figure 7. Number of challenging and replacement behaviors exhibited by Cody |

Limitations and Areas for Future Research

There were three major limitations in the present study that impact generalizability of reported results. First, extraneous variables occurred during observation sessions that were beyond the control of the primary researcher. All observation sessions were conducted in a high school life skills classroom where other students and school personnel were present. As a result, there may have been distractions that impacted the teacher’s use of behavior-specific praise or factors that provoked challenging behaviors among students. Future studies should attempt to create a more controlled classroom setting to reduce distractions and instigating factors as much as possible.

Second, the teacher-participant had several years of professional teaching experiences among students with disabilities. Additionally, the three student-participants were individuals with severe intellectual disabilities who each exhibited individualized challenging behaviors. Future studies should include teacher-participants with varying professional teaching experiences so that teachers in different teaching assignments (e.g., special education classrooms, content area classrooms) and at various stages of their teaching career may be evaluated. Future studies should also involve a greater number of student-participants with other types of disabilities who exhibit different forms, frequencies, and intensities of challenging behaviors.

Lastly, the present study used inter-observer agreement checks to establish reliability with intervention sub-phase observations. For each observation session, Kappa values were calculated and demonstrated good inter-observer agreement with all but two observation sessions. Future studies should incorporate ways to improve the degree to which multiple observers conduct consistent interpretations of events during the same observation session.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Among students with severe intellectual disabilities teachers can use PBIS practices, such as behavior-specific praise, to reduce the occurrence of challenging behaviors and promote alternate, replacement behaviors (Farmer et al., 2012). Since teachers are not adequately prepared or trained to use PBIS practices with fidelity (Kennedy et al., 2017), Stormont and Reinke (2014) recommended using a data-based performance feedback approach characterized with observations and consultations to provide teachers with visual performance feedback. The goal of the present study was to address an under-researched area and evaluate the effect of visual performance feedback on the frequency of (a) behavior-specific praise statements given by a high school special education teacher and (b) challenging and replacement behaviors exhibited by high school students with severe intellectual disabilities.

Results in the present study have shown that use of a data-based performance feedback approach enabled Ms. George to significantly increase the frequency of behavior-specific praise given to Kara, Chris, and Cody. By providing Ms. George with initial training and weekly consultations that included visual performance feedback, she was empowered to implement behavior-specific praise with fidelity. Results also revealed decreases in challenging behaviors and increases in replacement behaviors exhibited by student participants, especially with Kara. Reducing challenging behaviors in high school students with severe intellectual disabilities can be problematic because their behaviors have become deeply ingrained over time (Bruhn et al., 2016). This was evident in findings reported for Chris and Cody after the first intervention sub-phase. Despite this phenomenon, findings from the social validity questionnaire showed that Ms. George viewed behavior-specific praise as an effective PBIS practice that increased access to instructional opportunities for Kara, Cody, and Chris. Furthermore, Ms. George indicated that she planned to continue using behavior-specific praise with high school students who have severe intellectual disabilities.

Results from the present study have implications for stakeholders in teacher preparation programs and high school contexts. High school teachers who work among students with severe intellectual disabilities must know how to address challenging behaviors appropriately. Therefore, preservice and practicing teachers must learn how to conduct FBAs to determine the function of challenging behaviors and create function-based behavior improvement plans that implement PBIS practices as interventions (Erbas, Tekin-Iftar, & Yucesoy, 2006; Westing, 2015). Trainings should include frequent opportunities to observe experienced teachers and practice related skills in authentic high school settings (Mastropieri, 2001) using a visual performance feedback approach (Jenkins, Floress, & Reinke, 2015; Reddy, Dudek, & Lekwa, 2017; Stormont & Reinke, 2014). While implementing a data-based performance feedback approach, stakeholders in teacher preparation programs and high school contexts may also consider different variations with procedures. For example, video self-modeling enables teachers to view themselves performing PBIS practices successfully (Hawkins & Heflin, 2011). Additionally, teachers may be provided with performance feedback through email (Allday et al., 2012; Gage et al., 2018) or via real-time means using wireless technology devices (Sweigart et al., 2015).

References

Alberto, P. A. & Troutman, A. C. (2009). Applied behavior analysis for teachers. (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Allday, R. A., Hinkson-Lee, K., Hudson, T., Neilsen-Gatti, S., Kleinke, A., & Russel, C. S. (2012). Training general educators to increase behavior-specific praise: Effects on students with EBD. Behavioral Disorders, 37(2), 87-98. doi:10.1177/019874291203700203

Bruhn, A. L., Kaldenberg, E., Bappe, K. T., Brandsmeier, B., Rila, A., Lanphier, L., . . . Slater, A. (2016). Examining the effects of functional assessment-based interventions with high school students. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60(2), 106-116. doi:10.1080/1045988X.2015.1030721

Bryington, A. A., Palmer, D. J., & Watkins, M. W. (2002). The estimation of interobserver agreement in behavioral assessment. The Behavior Analyst Today, 3(3), 323-328. doi:10.1037/h0099978

Carr, E. G. (1977). The motivation of self-injurious behavior: A review of some hypotheses. Psychological Bulletin, 84(4), 800-816. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.84.4.800

Carr, E. G., Newsom, C. D., & Binkoff, J. A. (1976). Stimulus control of self-destructive behavior in a psychotic child. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 4(2), 139-153. doi:10.1007/BF00916518

Carter, E. W., Sisco, L. G., Chung, Y., & Stanton-Chapman, T. L. (2010). Peer interactions of students with intellectual disabilities and/or autism: A map of the intervention literature. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 35(3/4), 63–79. doi:10.2511/rpsd.35.3-4.63

Dixon, D. R., Vogel, T., & Tarbox, J. (2012). A brief history of functional analysis and applied behavior analysis. In J. L. Matson (Ed.), Functional assessment for challenging behaviors (pp. 3-24). New York, NY: Springer.

Drasgow, E., Yell, M. L., Bradley, R., & Shriner, J. G. (1999). The IDEA amendments of 1997: A school-wide model for conducting functional behavioral assessments and developing behavior intervention plans. Education and Treatment of Children, 22(3), 244–266. Retrieved from www.educationandtreatmentofchildren.net

Duchaine, E. L., Jolivette, K., & Fredrick, L. D. (2011). The effect of teacher coaching with performance feedback on behavior-specific praise in inclusion classrooms. Education and Treatment of Children, 34(2), 209-227. doi:10.1353/etc.2011.0009

Erbas, D., Tekin-Iftar, E., & Yucesoy, S. (2006). Teaching special education teachers how to conduct functional analysis in natural settings. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 41(1), 28-36. Retrieved from daddcec.org/Publications/ETADDJournal.aspx

Fabiano, G. A., Reddy, L. A., & Dudek, C. M. (2018). Teacher coaching supported by formative assessment for improving classroom practices. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(2), 293-304. doi:10.1037/spq0000223

Farmer, T. W., Lane, K. L., Lee, D. L., Hamm, J. V., & Lambert, K. (2012). The social functions of anti-social behavior: Considerations for school violence prevention strategies for students with disabilities. Behavioral Disorders, 37(3), 149-162. doi:10.1177/019874291203700303

Gage, N. A., Grasley-Boy, N. M., & MacSuga-Gage, A. S. (2018). Professional development to increase teacher behavior-specific praise: A single-case design replication. Psychology in the Schools, 55(3), 264-277. doi:10.1002/pits.22106

Gage, N. A., MacSuga-Gage, A. S., & Crews, E. (2017). Increasing teachers’ use of behavior-specific praise during a multitiered system for professional development. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19(4), 239-251. doi:10.1177/1098300717693568

Handleman, J. S. (1986). Severe developmental disabilities: Defining the term. Education and Treatment of Children, 9(2), 153-167. Retrieved from www.educationandtreatmentofchildren.net

Hanley, G. P., Iwata, B. A., & McCord, B. E. (2003). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(2), 147-185. doi:10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147

Hartmann, D. P., & Hall, R. V. (1976). The changing criterion design. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 9(4), 527-532. doi:10.1901/jaba.1976.9-527

Hawkins, S. M., & Heflin, L. J. (2011). Increasing secondary teachers’ behavior-specific praise using a video self-modeling and visual performance feedback intervention. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13(2), 97-108. doi:10.1177/1098300709358110

Iwata, B. A. (1987). Negative reinforcement in applied behavior analysis: An emerging technology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 20(4), 361-378. doi:10.1901/jaba.1987.20-361

Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1982). Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2(1), 3-20. doi:10.1016/0270-4684(82)90003-9

Iwata, B. A., Wallace, M. D., Kahng, S., Lindberg, J. S., Roscoe, E. M., Conners, J., . . . Worsdell, A. S. (2000). Skill acquisition in the implementation of functional analysis methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33(2), 181-194. doi:10.1901/jaba.2000.33-181

Jenkins, L. N., Floress, M. T. & Reinke, W. (2015). Rates and types of teacher praise: A review and future directions. Psychology in the Schools, 52(5), 463-476. doi:10.1002/pits.21835

Johnson, R. B., & Christensen, L. (2014). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Kalis, T. M., Vannest, K. J., & Parker, R. (2007). Praise counts: Using self-monitoring to increase effective teaching practices. Preventing School Failure, 51(3), 20–27. doi:10.3200/PSFL.51.3.20-27

Kennedy, M. J., Hirsch, S. E., Rodgers, W. J., Bruce, A., Lloyd, J. W. (2017). Supporting high school teachers’ implementation of evidence-based classroom management practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 47-57. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.009

Lane, K. L., & Wehby, J. (2002). Addressing antisocial behavior in the schools: A call for action. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 6, 4-9. Retrieved from rapidintellect.com/AEQweb/

Mastropieri, M. A. (2001). Is the glass half full of half empty? Challenges encountered by first-year special education teachers. The Journal of Special Education, 35(2), 66-74. doi:10.1177/002246690103500201

Matsushima, K., & Kato, T. (2015). Research on positive indicators for teacher-child relationship in children with intellectual disabilities. Occupational Therapy International, 22(4), 206–216. doi:10.1002/oti.1400

Medeiros, K. (2015). Behavioral interventions for individuals with intellectual disabilities exhibiting automatically-reinforced challenging behavior: Stereotypy and self-injury. Journal of Psychological Abnormalities in Children, 4(3), 1-8. doi:10.4172/2329-9525.1000141

Mesa, J., Lewis-Palmer, T., & Reinke, W. (2005). Providing teachers with performance feedback on praise to reduce student problem behavior. Beyond Behavior, 15(1), 3–7. Retrieved from journals.sagepub.com/home/bbx

Nijs, S., & Maes, B. (2014). Social peer interactions in persons with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: A literature review. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 49(1), 153-165. Retrieved from daddcec.org/Publications/ETADDJournal.aspx

Räty, L. M. O., Kontu, E. K., & Pirttimaa, R. A. (2016). Teaching children with intellectual disabilities: Analysis of research-based recommendations. Journal of Education and Learning, 5(2), 318-336. doi:10.5539/jel.v5n2p318

Reddy, L. A., Dudek, C. M., & Lekwa, A. (2017). Classroom strategies coaching model: Integration of formative assessment and instructional coaching. Theory Into Practice, 56(1), 46-55. doi:10.1080/00405841.2016.1241944

Reinke, W. M., Lewis-Palmer, T., & Merrell, K. (2008). The classroom check-up: A classwide teacher consultation model for increasing praise and decreasing disruptive behavior. School Psychology Review, 37(3), 315–332. Retrieved from naspjournals.org

Stormont, M., & Reinke, W. M. (2014). Providing performance feedback for teachers to increase treatment fidelity. Intervention in School and Clinic, 49(4), 219-224. doi:10.1177/1053451213509487

Sweigart, C. A., Landrum, T. J., & Pennington, R. C. (2015). The effect of real-time visual performance feedback on teacher feedback: A preliminary investigation. Education and Treatment of Children, 38(4), 429–450. doi:10.1353/etc.2015.0024

Vaughan, M. E., & Michael, J. L. (1982). Automatic reinforcement: An important but ignored concept. Behaviorism, 10(2), 217-228. doi:10.2307/27759007

Vollmer, T. R. (1994). The concept of automatic reinforcement: Implication for behavioral research in developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 15(3), 187-207. doi:10.1016/0891-4222(94)90011-6

Westing, D. L. (2015). Evidence-based practices for improving challenging behaviors of students with severe disabilities (Document No. IC-14). Retrieved from University of Florida, Collaboration for Effective Educator, Development, Accountability, and Reform Center website: ceedar.education.ufl.edu/tools/innovation-configurations/

Zirkel, P. A. (2017). An update of judicial rulings specific to FBAs or BIPs under the IDEA and corollary state laws. The Journal of Special Education, 51(1), 50-56. doi:10.1177/0022466917693386

About the Authors

Michelle Simmons. Ed.D., is an Assistant Professor of Special Education at West Texas A&M University. Dr. Simmons’ university responsibilities include program coordinator, advisor and instructor in the educational diagnostician, special education teacher preparation and special education graduate programs. Dr. Simmons has taught as a special educator at the secondary level both in special and general education settings. In addition to her instructional experience, Dr. Simmons served as an educational diagnostician at the elementary and secondary levels in urban and rural education settings. Dr. Simmons’ research focuses on best practice in assessment and evaluation, multicultural evaluation and instruction for students with disabilities, university-based special educator preparation programs, and behavior management strategies specific to students with intellectual disabilities.

Robin H. Lock, Ph.D., is the interim dean of the College of Education at Texas Tech University and is a professor in the college’s special education program. Her experiences building external partnerships and establishing The Burkhart Center for Autism Education and Research have led Dr. Lock is principal investigator for East Lubbock Promise Neighborhood (ELPN), a multi-institutional community engagement project funded by a $25 million U.S. Department of Education grant. In addition, Dr. Lock has garnered over $5 million in external funding – including private donations, foundation grants, state grants and federal funding – for work with individuals with disabilities, young people in the foster care system and other community engagement initiatives. Her research interests revolve around postsecondary educational opportunities for students with disabilities as well as those being served in the foster care system. She has over 35 publications, including a book, Assessing Students with Special Needs to Produce Quality Outcomes.

Janna Brendle, Ph.D., is an associate professor of special education in the College of Education at Texas Tech University. Dr. Brendle’s university responsibilities include program coordinator, advisor and instructor in the educational diagnostician, special education teacher preparation and special education doctoral programs. Dr. Brendle’s research focuses on high incidence disabilities and instructional strategies and intervention for students with disabilities.

Laurie A. Sharp, Ed.D., is the Assistant Dean for Undergraduate Studies for First and Second Year Experience and Associate Professor at Tarleton State University in Stephenville, Texas. Dr. Sharp promotes student success among adult learners, actively participates in professional service, and maintains an extensive scholarship record.

The Changing Role of the Itinerant Teacher of the Deaf: A Snapshot of Current Teacher Perceptions

Holly F. Pedersen, Ed.D.

Minot State University

Karen L. Anderson

Supporting Success for Children with Hearing Loss

Abstract

The past two decades have seen unprecedented changes to the field of deaf education. Several factors including technological advances and educational policy have resulted in the inclusion of the majority of students who are deaf or hard of hearing in the general education classroom with various levels of support services. Consequently, the role of the professional educator of the deaf has changed to the itinerant teaching model as the primary service delivery system in deaf education in the nation today. Because this role for teachers of the deaf is evolving, ongoing research is necessary to identify emerging trends, successes, and potential barriers to ensure effective service provision to students who are deaf or hard of hearing. This study sought to obtain a current picture of the roles and responsibilities of the itinerant teacher of the deaf (ITOD) via an electronic survey conducted through postings on a well-known professional website. Participants were 267 itinerant teachers of the deaf. Survey results support previous findings that lack of awareness of the needs of this population of students and lack of time due to increasing caseloads are barriers to service provision. Teachers reported being better prepared for the itinerant role in their preservice program than in past studies, and the use of mentorship appears to be an emerging teacher support strategy. Results supported the adequacy of the itinerant model in supporting students who are above, at, or within 6 months of grade level expectations, with increasing concerns about the ability to provide adequate levels of support to students in inclusive settings with greater educational delays via the itinerant model. Implications for these findings for the field as well as potential questions for future research on this topic are discussed.

Keywords: itinerant, deaf education, survey, service delivery model

Introduction

Before 1975, more than 85% of deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) students attended specialized schools; today more than 85% of students are in general education settings (Shaver, Marschark, Newman, & Marder, 2014). Reasons for this statistical flip include the inclusion movement, early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI) programs, and technological advances. The trend of DHH students attending their local school and receiving instruction in the general education classroom is expected to continue. Consequently, the primary model of service delivery for DHH students currently in the United States is itinerant services from a teacher of the deaf (ITOD) (Antia, 2013; Luckner & Ayantoye, 2013). An ITOD is defined as a “professional who provides instruction and consultation for students who are deaf or hard of hearing and most generally travel from school to school” (Luckner, 2006, p. 94).

Previous studies have sought to investigate ITOD roles, challenges, and perceptions. Early research identified itinerant practices in deaf education as differing significantly from traditional deaf education models particularly in the amount of time spent by the ITOD in non-teaching activities such as travel, in supporting the general education teacher, and in serving a wide range of students across grades and need intensities (Luckner & Miller, 1994; Yarger & Luckner, 1999). In the 2000s, research continued to confirm early findings and expand our understanding of this professional role. The importance of the ITOD being able to effectively communicate with a variety of other professionals as well as the potential isolation an ITOD may experience were highlighted in studies by Luckner and Howell (2002) and Kluwin, Morris and Clifford (2004). Foster and Cue (2009) surveyed 210 ITODs and found that services to DHH students comprised the primary duties of the ITOD, and consultation to other professionals the second; although, a shift towards increasing amounts of consultation or indirect services was noted. A second study surveying 356 ITODs (Luckner & Ayantoye, 2013) confirmed Foster and Cue’s findings that ITODs ranked services to DHH students as their most important duty and consultation to other professionals and parents and the second.

Common challenges experienced by ITODs repeatedly appear in the research. Overwhelmingly, ITODs report lack of time as a significant barrier (Luckner & Dorn, 2017; Antia & Rivera, 2016; Compton, Appenzeller, Kemmery, & Gardiner-Walsh, 2015; Luckner & Ayantoye, 2013; Foster & Cue, 2009); specifically, increasing caseloads of students spread out amongst many school buildings and insufficient time for collaboration with other team members. Additional barriers faced by ITODs include difficulty scheduling services, navigating state and district policies, lack of follow-through by other team members, lack of administrative support, professional isolation, and stress and burnout (Antia & Rivera, 2016; Kennon, & Patterson, 2016). Finally, the issue of pre-service and in-service preparation has been discussed in the literature. Foster and Cue (2009) found that the majority of ITODs they surveyed learned their skills on the job and felt ill-prepared for this role by their pre-service programs. Additionally, ITODs from this study wanted professional development that focused specifically on the needs of ITODs. Later research confirmed that university programs were still not effectively preparing teachers of the deaf for itinerant roles, but that satisfaction with professional development on this topic was increasing (Luckner & Ayantoye, 2013).

In recognition of the evolving roles and responsibilities of the ITOD, the purpose of this study was to update current understandings by providing a snapshot of current ITOD practices and perceptions. Specific research questions posed were, 1) What do the caseloads of ITODs look like? 2) What is the nature of services ITODs provide and how do they view the adequacy of these services? 3) Do ITODs perceive their preparation programs equipped them for this role?, and 4) How do ITODs perceive professional administrative support?

Method

The current study utilized a quantitative survey design with the data source being responses to 10 questions (each with subquestions) on an electronic survey. The survey was developed using Survey Monkey and was distributed to over 11,800 subscribers of Supporting Success for Children with Hearing Loss (SSCHL) in their bi-monthly update and was available for a period of one month. SSCHL, is a ‘go-to’ site for professionals and family members seeking more information about hearing loss and what can be done to better support the future learning and social success of children with hearing loss. It receives approximately 20,000 unique hits per month. Professionals, identifying as teachers of students who are deaf or hard of hearing who provide itinerant services, were invited to complete the survey. Survey items were developed with the desire to investigate the perceptions of ITOD on their roles and responsibilities, especially regarding caseload variations, inclusion practices, experience in the field, and perceived level of supervisor support. In total, 267 ITODs completed the survey. Descriptive analysis of frequency counts, means, and medians of the data were calculated using Excel. Results of this analysis are displayed below in narrative and graphic representations.

Results

Participants. The 267 ITODs who responded to the survey were balanced between novice and veteran teachers: 32% have been an ITOD for 1-5 years, 21% for 6-10 years, 19% for 11-15 years, 9% for 16-20 years, and 16% for 21 or more years. Of the total number, 40% indicated they are planning on leaving the field within five years. Part-time teachers comprised 11% of respondents. About 60% of the respondents have served in the role of ITOD in a center-based or resource room program, but are currently working in an ITOD role or providing services in both center-based and itinerant service models.

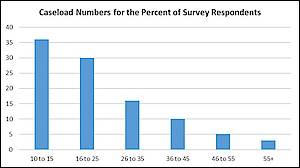

Caseload. The majority of ITODs in the study had caseloads ranging 10 to more than 55 students. Caseload size by percentage of participant were as follows: 10-15 students: 36%, 16-25 students: 30%, 26-35 students: 16%, 36-45 students: 10%, 46-55 students: 5%, and more than 55 students: 3%. Of the total student caseload, DHH students with additional needs (DHH+) comprised approximately 30% of participant caseloads. ITODs served an average of 10.6 buildings per month, with the range being 1-60 buildings and a median of 9 buildings. Figure 1 displays reported caseload size.

Figure 1. Caseload Size

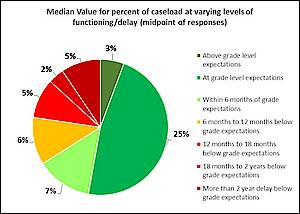

Participants were asked about the grade level performance of DHH students on their caseload with no additional disabilities. Respondents considered their caseloads and identified the percent of their caseloads that were performing at each of the identified grade level performance descriptions. The median, or the center point at which 50% of the responses are below, and 50% of responses are above, are reported as being most representative for this body of data. Figure 2 shows the median values for percentage of caseload performance relative to grade level.

Figure 2. Caseload Performance Relative to Grade Level Expectations.

The median value for the percentage of caseload functioning at grade level was 25%. There were relatively few students served who were felt to be exceeding grade level expectations. Median values were similar at 6-7% of caseload functioning within one year of grade level and the same at 5% of caseload behind grade level by more than one or two plus years. The median percentage of caseload that was functioning above grade level was 3%.

Nature of Service Delivery. To develop a picture of the various aspects of service provision to DHH students from ITODs, several survey questions addressed this topic. Questions were related to service models, frequency, intensity, perceived adequacy of services as well as perceptions of Individualized Education Planning and the impact of full-inclusion models.

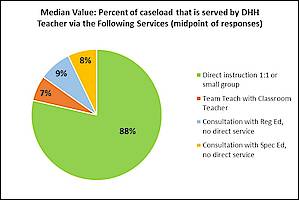

Direct vs. Indirect. Participants were asked what percentage of DHH students on their caseload received services categorized by one of four types 1) direct one on one or small group, 2) consultation only to special educators, 3) consultation only to general educators, and 4) team teaching. As shown in Figure 3, participants indicated the majority of services they provided to DHH students on their caseloads were one on one or small group direct services at 88%. Consultative only services to regular education teachers were provided second most frequently at a median of 9% of caseloads and consultation only services to special education teachers occurred for a median of 7% of caseloads. Team teaching only occurred for a median of 8% of caseloads of the services ITODs in this study were providing.

Figure 3. Median Percentages of ITOD Services Provided by Type

Relative to students who are DHH+, the median response for participants indicated that 31% of caseloads were comprised of students with hearing loss plus other disability conditions. When asked what percentage of their caseload received direct ITOD services versus consultation only, the median responses indicated 75% of DHH+ students receive direct ITOD services, and 20% receive consultation only. Respondents further indicated that they felt that 90% of students who are DHH+ receive an appropriate amount of service.

Intensity of Services. For DHH students on their caseloads whose only disability is hearing loss, participants were asked to indicate what percentage of these students were receiving direct ITOD service minutes in each of nine possible time options. In rank order from the most common service minutes amount provided, to the least common amount of minutes provided, frequency counts indicate the following:

- 45 minutes per week (median 30%).

- 4-5 hours per week (median 11%).

- 3-4 hours per week (median 10%)

- 90 minutes per week and 30 minutes per week (tied at a median of 8%)

- 2-3 hours per week and 1 hour per month (tied at a median of 1%)

- 60 minutes per week and 30 minutes per month were negligible

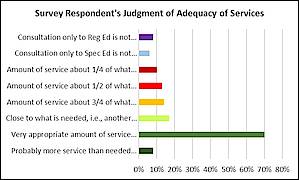

Adequacy of Services. Participants were asked to judge whether or not the amount and type of services they were providing were adequate for DHH students on their caseloads who had no additional disabilities and for those students who are DHH+. When asked what percentage of their caseload of DHH-only students fell into certain levels of adequate services, median values for percent of caseloads are as follows: 1) very appropriate level of services to meet the needs = 70%, 2) close to what is needed to meet the needs = 17%, 2) about ¾ of what is needed to meet the needs = 14%, 3) about half of what is needed to meet the needs = 13%, 4) about ¼ of what is needed to meet the needs = 10%, and 5) probably more service than needed = 8%.

Participants were also asked the percentage of their DHH only students whose needs were not being met through consultation only to either the general education teacher or the special education teachers. The median value for consultation only to the general education teacher was 8% and 6% to the special education teacher.

Thus, as summarized in figure 4, the responding teachers felt that the majority of their caseloads were receiving very appropriate (70%), close to what is needed (17%), or service that exceeds needs (8%). The results of a prior survey question indicated that of caseloads, the median number of students who were one year delayed in grade level expectations was 5%, 1.5 years delayed was 2% and greater than two years delated was 5%. The model of ITOD service provision is likely insufficient to provide for the needs of students with these more extreme levels of need, thus creating a situation in which teachers perceive that a substantial proportion of ITOD caseloads are felt to be underserved by ¼ (14%), ½ (13%), or ¾ (10%) of the service time actually needed. Part of this dissatisfaction may additionally be explained by the concerns that consultation only services are not sufficient to meet student needs.

Figure 4. Median Percentages of Perceived Adequacy of Services.

Individual Education Plans and Inclusion. Two survey questions were designed to gather data regarding ITOD perceptions of the IEP process and the perceived impact of the full-inclusion models on their practices. Tables 1 and 2 display the survey statements and the corresponding percentage of ITODs that answered true for each statement. The result indicated more than half of the respondents perceived limited time and lack of understanding of DHH needs by other IEP team members as the greatest barriers to service provision. While nearly half of the responding ITODs are working in districts that have not embraced a full inclusion model, participants did indicate experiencing pressure to move to more indirect delivery (consultation) in lieu of direct services. Furthermore, less than 10% of participants indicated their districts had provided professional development for inclusive service delivery.

Table 1

ITOD Perceptions of the IEP Process

|

Survey Statement |

Percentage of Participants Answering True |

|

I have a lot of schools and only so much time available. When a new student is identified, I can only serve him/her the amount of time I can free up on my schedule, even if there is a clear need for more direct DHH service time. (My administration knows this and is not interested in hiring more DHH staff). |

51.46% |

|

The IEP teams usually underestimate the level of student needs, thereby specifying DHH services that are not as intense/frequent as are needed by most/many of my students. |

50.49% |

|

My district uses a service matrix or some other standard process when considering the amount of service time that each student needs. |

25.24% |

|

We are an ‘inclusion school district,’ and all pull-out services are highly discouraged, even if a student has one year or greater learning delays. |

21.84% |

|

My administration has told me that I can only spend a certain amount of direct service time (or maximum amount) with any one DHH student. |

19.90% |

|

My administration has told me that I can only provide consultation to the teachers that serve the identified students who are DHH (or there are clear guidelines on when DHH direct services will be allowed). |

12.14% |

|

My district uses a service matrix or some other standard process when considering the amount of service time that each student needs. |

25.24% |

Table 2

ITOD Perceptions of Full-Inclusion Impact

|

Survey Statement |

Percentage of Participants Answering True |

|

Does not apply. My district has not embraced ‘full inclusion practices,’ or these practices have been deemed to not apply to (most) students with hearing loss. |

45.78% |

|

My district has provided little or no training in team-teaching and/or consultation when supporting the DHH student in the inclusive model. I do not feel comfortable in this role. |

30.12% |

|

Fewer pull-out direct services are being allowed. |

27.71% |

|

All or almost all special ed services are provided by a small special education teaching staff and aides. Inclusion in this case, means I consult with the special education staff so they will address the DHH specific needs within the class or during ‘study session’ pull out. |

24.50% |

|

Consultation is being recommended instead of direct service. |

20.88% |

|

Team-teaching is being encouraged instead of direct service. Classroom teachers are generally welcoming when I come in to teach lessons to the class or a small group. |

9.64% |

|

My district has provided training in team teaching and/or consultation when supporting the DHH student in the inclusive model. I feel comfortable in this role. Administration has helped to make classroom teachers understand these changes and the purpose of my DHH services. |

7.63% |

|

Team teaching is being encouraged instead of direct service. Classroom teachers are often resistant to collaborative planning and when I come in to teach lessons to the class or a small group. |

7.23% |

|

Consultation is being recommended instead of direct service. |

20.88% |

|

My district has provided training in team teaching and/or consultation when supporting the DHH student in the inclusive model. I feel comfortable in this role. Administration has helped to make classroom teachers understand these changes and the purpose of my DHH services. |

7.63% |

|

My district has provided training in team teaching and/or consultation when supporting the DHH student in the inclusive model. I need more training and support from administration to feel comfortable in this role. |

5.22% |

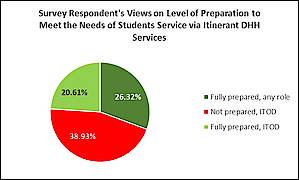

Preparation. The survey included questions about the level of preparation the respondents felt they received from their preservice university training program to fulfil the various roles a teacher of the deaf and hard of hearing could assume, including that of itinerant teacher of the deaf and hard of hearing.

Table 3

ITOD Perceptions of University Preparation

|

Survey Statement |

Percentage of Participants Answering True |

|

My university training program prepared me to teach and support academics to a small group of students who are deaf or hard of hearing. I was not prepared (adequately) to fulfill the role of an itinerant teacher of the deaf and hard of hearing. |

38.93 |

|

My university training program prepared me for any role as a DHH teacher – school for the deaf, center-based program, resource room, itinerant, team-teacher, consultant. |

26.32 |

|

My university training program did a good job of preparing me to work as an itinerant teacher of the deaf/hard of hearing. |

20.61 |

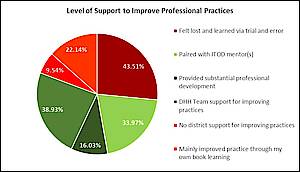

For preservice preparation, results were mixed with slightly more teachers indicating their university program did prepare them for itinerant work than not. Participants were also asked to comment on how well prepared they felt to meet the needs of DHH+ students on their caseloads. Figure 5 indicates that 63% of ITODs felt mostly or fully prepared to serve DHH+ students while 26% said they felt fairly prepared, and 11% said they felt only a little prepared or not at all prepared.

Figure 5. Perceived Preparedness to Serve DHH+ Students