Table of Contents

- Special Education Legal Alert. By Perry A. Zirkel

- Buzz from the Hub

- Supports in Equity: Universal Design for Learning for Students with Disabilities in Higher Education. By Melissa Beck Wells, EdD

- Better Together on Behalf of Our Children. By Samantha Ashley Forrest

- Using Visuals to Teach Phonics: Sand, Pictures, and iPads. By Amanda Gyemant and Min Mize

- The Curious Case of Fragile X Syndrome. By Anthony Ruggiero

- Book Reviews

- Acknowledgements

Special Education Legal Alert

By Perry A. Zirkel

© July 2020

This month’s update concerns issues that were subject to recent court decisions of general significance: (a) child find, evaluation, eligibility, and remedies for a child with excessive absenteeism, and (b) transfer of rights upon reaching the age of majority.

|

In an officially published decision in Independent School District v. E.M.D.H. (2020), the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals addressed various eligibility-related issues for a gifted secondary school student with an array of diagnoses including school phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, severe depression, and panic disorder. In grade 8, her absences became increasingly more frequent until her parents placed her in a psychiatric treatment facility. Aware of her mental health issues, her teachers marked her final grades as Inc. rather than F. The attendance pattern recurred in grades 9 and 10, with increasing absenteeism leading to disenrollment for psychiatric treatment. The parents did not request an evaluation for special education until her readmission to a psychiatric facility in April of grade 10, because school personnel informed her that her placement would change from honors classes. The district did not complete the evaluation until November of grade 11, concluding that she was not IDEA-eligible. The parents responded by arranging for an IEE, which confirmed her diagnoses and recommended that she receive special education that would allow her to complete honors coursework. The district rejected the recommendations, and the parents filed for a due process hearing. The hearing officer ruled in their favor and ordered reimbursement for the IEE and tutoring expenses, quarterly IEP meetings, and future compensatory services. The district court affirmed with the exception of the future services. Both parties appealed to the Eighth Circuit. |

|

|

First, the court rather easily upheld the child find violation, concluding that the district had the requisite reasonable suspicion as early as the end of grade 8. |

The district raised a statute of limitations defense, but the court concluded that even if the end of grade 8 was beyond the statutory two-year period, the child find violation “was not a single event … [but] was repeated well into the limitations period” |

|

Second, the court ruled that the district’s eligibility evaluation fatally failed to comply with the Minnesota state law requirements for an FBA and systematic observations upon evaluating for ED or OHI. |

Observing that the district had made no effort at all to comply, the court rejected the district’s defense in emphatic terms: “We acknowledge that while the Student’s absences might have made a comprehensive evaluation more difficult, the evidence does not support the conclusion that task was impossible to undertake.” |

|

Third, the court upheld the eligibility violation, finding fault with the district’s rationales about both the student’s high absenteeism, which was linked to her disability, and her high intellect, which did not foreclose being IDEA eligible. |

The court concluded that student’s absenteeism was not “as a result of ‘bad choices’ …, but rather as a consequence of compromised mental health” and that it put her behind her peers in credits for graduation, thus having an adverse effect on her educational performance. Similarly, the court observed that the evidence was that this child needed special education to progress academically despite her giftedness. |

|

Finally, the court not only upheld all of the other remedies, but also reinstated the compensatory education award of private tutoring until the student no longer has the credit deficiency from the FAPE denial. |

The court concluded that in light of the district’s continued and cumulative denial of FAPE, these equitable remedies were within the hearing officer’s remedial discretion, and that none of this relief would have been necessary if the district had met its IDEA obligations to this student in the first place. |

|

The bottom line is obvious: make careful determinations rather than kneejerk reactions in response to student’s absenteeism or giftedness. |

|

|

Two recent decisions illustrate various issues that may arise when a student with disabilities reaches the age of majority: • In Butte School District No. 1 v. C.S. (2020), the Ninth Circuit addressed the several claims that a 24-year-old with multiple disabilities, including autism and ED, and his caregiver originally brought in a due process hearing specific to his IEPs in grades 11 and 12. In March of his 11th grade, C.S. reached the age of 18 and moved to live with his caregiver. At that time, because C.S. lacked the capacity for informed consent, the caregiver sought appointment as his educational representative; however, the district appointed a surrogate parent. At the end of grade 12, C.S. refused the district’s offer of ESY and compensatory education, insisting instead on graduation. A year after graduation, C.S. and his caregiver filed for a due process hearing. The hearing officer ruled that the district provided FAPE in C.S.’s senior, but not his junior, year, and awarded him compensatory education for that denial. Upon both sides’ appeal, the federal district court concluded that it lacked authority to order C.S. to participate in the compensatory education or appoint his caregiver as decision maker but nevertheless proceeded to address the various claims. The court ruled that the district had not denied him FAPE for either year. C.S. and his car giver then appealed to the Ninth Circuit. • In Doe v. Westport Board of Education (2020), the parents filed for a due process hearing for tuition reimbursement for a unilateral placement for the senior year of a student with disabilities. He reached age 18 in May of that year, and his parents filed for the due process hearing two months later. The hearing officer granted the district’s motion for dismissal, and the parents appealed to the federal court in Connecticut. |

|

|

In the first of its Butte rulings, the Ninth Circuit rejected their claim that the district failed to evaluate C.S. for SLD despite having reasonable suspicion of areas of this additional disability classification during the first part of grade 11. |

The reasons were that (1) C.A.’s parent, who was still representing him at that time because he had not yet reached age 18, refused consent for that additional evaluation, and, in any event (2) his grade 11 and 12 IEPs included services in the suspected areas of SLD. |

|

Second in Butte, the Ninth Circuit rejected their claim the two successive IEPs were inappropriate due to the lack of an FBA and effective behavioral interventions. |

The court reasoned that the IDEA only requires an FBA for a disciplinary change in placement and that the BIP and other behavioral provisions of the IEPs met the Endrew F. standard. |

|

Third in Butte, the Ninth Circuit rejected their claim that the two IEPs were inappropriate in terms of sufficient assessments and goals for transition services. |

Assuming without deciding that the district committed these procedural violations, the court concluded that they were harmless because C.S. benefited from a host of transition services during both years. |

|

Finally in the Butte case, the Ninth Circuit addressed their claim that the district should have appointed the caregiver, not a surrogate, to represent C.S. because the Montana Supreme Court had ruled that his caregiver qualified as his foster parent. |

The court agreed that the lower court erred by not requiring the caregiver to be his decision maker in light of the relevant provisions of the IDEA and the state law ruling of the state supreme court. However, the court concluded that this procedural violation was harmless because the caregiver had continued to represent C.S. at the IEP meetings after he reached age 18. |

|

In the Westport case, the court upheld the dismissal of the parents’ claim based on the plain and unambiguous meaning of the IDEA transfer of rights provision. |

The court disagreed with and distinguished the opposite outcome in the District of Columbia’s Latynsky-Rossiter v. D.C. (2013). One of the differences was the clear operation of Connecticut’s corollary state law. |

|

The bottom line is that when the student with disabilities reaches age 18, pay careful attention to the relevant provisions of the IDEA and any pertinent corresponding provisions of the law in your state. |

|

Buzz from the Hub

All articles below can be accessed through the following links:

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-june2020-issue2/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-july2020-issue1/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-from-the-hub/

The Ultimate Parents’ Guide to Summer Activity Resources

To give parents a sense of the summertime fun can be had, the Washington Post compiled resources in 10 categories: reading, education, travel, mental wellness, music, art, physical activity, theater and dance, languages, and entertainment.

Parent Advocacy Toolkit for Equity in Use of COVID-19 Funds

NCLD and 13 partner organizations released recommendations to guide how the use of funding can prioritize equity and ensure our most vulnerable students receive the greatest support. Based on these recommendations, NCLD also created a 12-page toolkit to help parents advocate for equity as school districts develop reopening plans for the 2020-2021 school year.

COVID-19 Planning Considerations: Guidance for School Re-entry

This guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics supports education, public health, local leadership, and pediatricians collaborating with schools in creating policies for school re-entry that foster the overall health of children, adolescents, staff, and communities and are based on available evidence.

Special Report | How We Go Back to School

To reopen schools in the fall, K-12 leaders must balance three critical, often competing responsibilities: the health and safety of their people, the role their schools play in the larger community, and the effective teaching of their students. To help district and school leaders navigate these monumental decisions, Education Week lays out the big challenges ahead and some solutions in an 8-part series.

Spanish-Language Webinar on the Transition to Kindergarten Amid COVID-19

The transition into kindergarten marks a major milestone in a child’s life. The ED-funded Early Learning Network presents this 33-minute webinar specifically designed for Spanish speaking families to help families prepare their child for a successful transition into kindergarten during the pandemic.

The National Responsible Fatherhood Clearinghouse

Funded by HHS, this clearinghouse disseminates current research and innovative strategies to encourage and strengthen fathers and families. Many resources are also available in Spanish.

What’s Important to Native Youth?

Do you know? Find out in the infographic and brief developed to summarize the findings of a survey of Native youth and what they had to say. It will certainly inform your outreach to and work with youth.

Reinforcing Resilience: How Parent Centers Can Support American Indian and Alaska Native Parents

Considering the traumas that indigenous peoples have survived all these years and the current challenges they face, resilience is an essential quality to have. Here’s how Parent Centers can add value and vigor to an essence that has historically been integral in Native life.

Bouncing Back from Setbacks: A Message for American Indian and Alaska Native Youth

This brief is written directly to Native youth, as if it were a letter coming from the local Parent Center. It highlights 10 skills known to be builders of resilience in youth. Also available online in HTML.

We hope you enjoy the multicultural journey that all of the resources in Working with Native Children and Youth will take you on!

Will Your Schools Re-Open? What’s the Plan, Stan?

Johns Hopkins University has launched a new tracker that analyzes school reopening plans across the country. The tool examines whether or not each state reopening plan addresses a dozen different issues. You can also download state plans directly from the tracker. How timely, eh?

2020 Determination Letters on State Implementation of IDEA

How well are the states and territories implementing IDEA? The 2020 determination letters will tell you. (Can you guess who received the “needs intervention” determination for the ninth year in a row?!)

Comparison Guide: Video Conferencing Tools for Your Nonprofit

As nonprofits continue to do their work remotely, the need for a solid video conferencing tool has never been greater. TechSoup created this at-a-glance guide to help nonprofits make informed decisions about choosing what’s right for their organization.

Tech Soup Courses for Free!

TechSoup has also created a free track of courses to provide information and tools as nonprofits scale up the work they do remotely, including having necessary tech tools, how to boost collaboration, and how to ensure information security.

Camp Kinda

(In English and Spanish) | Here’s a free, virtual summer camp experience designed to keep kids engaged, asking questions, and having fun even while they’re stuck at home. “Open” each weekday starting June 1 to September 1. On any given day, kids may be exploring the art of graphic novels, unlocking the mysteries of history, or jumping into the world’s craziest sports. Also available in Spanish.

How to Support Your Unique, Quirky Child

(In English and Spanish) | When your child behaves differently from others, it’s endearing—but is it OK? Read this Great Schools article to find ways to celebrate your child’s unique nature. A version in Spanish is also available: Cómo apoyar las características únicas de tu hijo.

Video | The CDC Guidance on Reopening Schools, Explained

CDC recently released guidance on reopening schools. Its recommendations, which are voluntary, give parents and teachers their first detailed glimpse of how schools might change their operations to contain COVID-19. How much these recommendations will influence schools’ operations depends on the decisions of state and local leaders. Watch Education Week’s 4-minute video for an explanation of several key points.

SAVE the DATE | Webinar on Monday, June 8th @ 3 pm EDT

Safeguarding Back to School: Principles to Guide a Healthy Opening to Classrooms During COVID-19

The transition back to school this year will be unlike any in history. How do we safely reopen? In this edWebinar, leaders of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and Brooklyn Laboratory Charter Schools will discuss key questions we must all consider as we begin the journey back to school–from the school bus ride to the dismissal bell. Register here. If you’d like to receive an email with a link to the recording afterwards, add your name to the list at: https://forms.gle/V6mgSp8n8fqxjv318

Supports in Equity: Universal Design for Learning for Students with Disabilities in Higher Education

Melissa Beck Wells, EdD

College students are more diverse in race, ethnicity, and ability than ever before (Espinosa, Turk, Taylor, & Chessman, 2019). It is imperative that higher education is aware of the needs of its students and has a plan and a guiding framework to ensure that all students are provided the supports they need to achieve the high standards of the learning institution.

The high school graduation rate of students with disabilities has been steadily increasing throughout the United States. About 70% of high-school-aged students receiving special education services graduated with a regular high school diploma in the 2014-2015 school year, up substantially from the 27% receiving regular diplomas nearly 20 years earlier. (Congressional Research Service, 2017). This could be in part because students have been supported with scientifically derived or evidence-based validated techniques in their K-12 experience. Students with disabilities who have seen success in their K-12 education may rely on the consistency, reliability, and effectiveness to achieve academically. However, the use of scientifically validated frameworks of support may not be widespread in higher education institutions.

Without the framework and support for diverse students, many will not succeed. Research is lacking in the completion of a four-year degree program; however, in 2011, research shows that only 34 percent of college students with disabilities complete a four-year program as opposed to 54 percent of students without disabilities.

The expansion of research for graduation rates for higher education students with disabilities is needed. Without this information, a critical portion of our higher education student body is left behind. The National Center for College Students with Disabilities (NCCSD), found “There is no consistent way to track retention and graduation rates of students with disabilities in the U.S., and much of the research uses special education disability terms or incomplete disability categories (instead of higher education disability categories), or only tracks high school students with special education services (and not 504 plans) as explained in the NCCSD research brief on databases.”.

What can higher education do to mimic the continued positive graduation results for students with disabilities from high school? Perhaps it is not to reinvent the wheel but learn from what K-12 schools are implementing in terms of supports and mimic them.

One increasingly supported framework by researchers as well as federal legislation is the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.) to support students is the Universal Design for Learning (UDL). UDL is a scientifically validated framework aimed at increasing the learning experience for individuals, by offering flexibility in the way information is presented, in the way students and educators are engaged, and in the forms, students and educators are able to respond or demonstrate learning (CAST, 2018).

The goal of this framework is to reduce barriers of instruction, provide appropriate accommodations, supports and challenges, and maintain high achievement expectations for all students, especially within a heterogenous and inclusive student population (Novak, 2019).

Implementation of the UDL principles framework has demonstrated improved learning experiences for students in K-12 classrooms (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014). Research also finds that furthering the impact of UDL to higher education institutions would continue the positive effect on students (Gradel & Edson, 2009). Further, due to the flexibility and adaptability of the framework, higher education institutions can adapt with the institution’s mission, culture, and availability in mind.

Not only will student outcomes improve, but Tobin and Behling (2015) suggest UDL increases access for everyone, and institutions could measure that impact in terms of improved retention rates, financial savings, increased website traffic, and better student-ratings data.

Additionally, in the time of movement from traditional face to face classrooms and an increase of online learning, how can we ensure justice is served to students with disabilities who enroll in these classes? Linder, Fountaine-Rainen, and Behling’s (2015) research found, out of over 190 colleges and universities across the United States, few campuses are taking actions to adopt UDL thinking for their online courses or course components. The most significant reason that the issue is not receiving more attention falls to the lack of time, expertise, and resources that higher education institutions have at their disposal.

Ultimately, higher education institutions require training and retraining of faculty, and staff, perhaps led by the Disability Accommodations Office, to ensure equity among students with varying abilities in higher education. UDL is a flexible, meaningful, and scientifically proven framework to support all learners, particularly the marginalized group of students who identify as having a disability.

References

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from udlguidelines.cast.org

Congressional Research Service. (July 10, 2017). Retrieved on May 20, 2020. Students with Disabilities Graduating from High School and Entering Postsecondary Education: In Briefs. Retrieved from www.everycrsreport.com/files/20170710_R44887_44f9ad63208ab839433a798210d3a3e1c6980425.pdf

Espinosa, L.L., Turk, J.M., Taylor, M., and Chessman, H.M. (2019). Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: A Status Report. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Gradel, K., & Edson, A. J. (2009). Putting Universal Design for Learning on the Higher Ed Agenda. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 38(2), 111–121. doi.org/10.2190/ET.38.2.d

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and Practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST Professional Publishing.

National Center for College Students with Disabilities. (n.d.). Retrieved on May 20, 2020. General Statistics about College Students with Disabilities and Disability Resource Offices. Retrieved from www.nccsdclearinghouse.org/stats-college-stds-with-disabilities.html

Novak, K. (2019). UDL. What really works with universal design for learning, (pp 1-20). Corwin, A SAGE Publishing Company, Thousand Oaks, California.

Tobin, T., & Behling, K. (2018). Reach everyone, teach everyone: Universal design for learning in higher education (First edition.). Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

Better Together on Behalf of Our Children

Samantha Ashley Forrest

Abstract

“Better Together on Behalf of Our Children” by Julie Simone, Ally Hauptman, and Michelle Hasty is an article that focused on empowering the partnership between home and school to foster more authentic literacy experiences and to assist children to become better readers and writers. The article consisted of state funded summer camps that participated in a study focused on with parents and highly qualified educators to discuss what literacy practices that were conducted at home and provided more support of enrichment practices to help families. The study worked economically disadvantaged children by supporting them with four – hour long literacy related learning experiences, within 20 consecutive days; in which, they were able to take home themed based books that were discussed with parents to build their home libraries. The educators were able to look at their state’s specific literacy goals and add to what the parents were already doing at home. The authors were able to create an enriched literacy program that used local communities to help families explore ways and add more to what they were doing at home. These authentic approaches helped parents and students become more engaging and therefore, lead to an increase in the reading comprehension rates among their children.

Critical Reflection

“Better Together on Behalf of Our Children” was written by Julie Simone, Ally Hauptman, and Michelle Hasty that focused on authentic literacy experiences to empower children to become capable readers and writers through a school and family partnership. The purpose of the study was to determine: “What will make a difference in these striving readers’ lives (Simone, Hauptman, & Hasty, 2019)?” The study worked with funding 20 pilot summer camps that served 598 students and facilitated by 114 highly qualified teachers with literacy experience for about three years (Simone, Hauptman, & Hasty, 2019). The camps ran for 20 days with four – hour long literacy – related learning experiences per day and children were able to select a minimum of six books to take home to create their own libraries (Simone, Hauptman, & Hasty, 2019). The children in this study were considered economically disadvantaged students among the first through third graders.

The authors partnered with teachers and parents to build a strength – based approach in which “everyone is seen as already capable, already learning, and already contributing (Simone, Hauptman, & Hasty, 2019).” This approach allows all participates to share responsibility on how to better foster literacy achievement for these striving children. The mixed method study used both qualitative and quantitative data to engage children in a more authentic approach to literacy with values determined by school and home relationship. Before the summer camps started, parents and teachers would attend professional developments to collaborate on the literacy practices in their homes and communities and work to get an enrichment plan for the program. This would better support and encourage parental support of meeting literacy expectations. The authors worked with the teachers to distinguish what are their state’s specific goals on literacy developments among the different grade levels to help achieve their state’s goal of moving third – grade reading proficiency to 75% by the year 2025 (Simone, Hauptman, & Hasty, 2019).

The mixed method of the data helps the reader to build a better picture of what the study consisted of. The narrative qualitative method of the study established how both school and home were communicating to foster the summer camp programs. From the parental contribution, the program as able to get themed books that the children could select to ensure the meanings of morals and values that the parents wanted the children to get from the literacy program. The quantitative data was allowing the educators to see the children’s deficiencies in reading, to assist them with better instructions and finding materials; for example, flash cards to help them at home. In addition, the researchers also partnered with local businesses in the community to create more real world literacy approach from using a local truck company’s drivers to share their travels and adventures to a baseball park providing opportunities for the children to explain the events in a given game and what information could be used for support details (Simone, Hauptman, & Hasty, 2019). Their findings show an increase of confident readers and writers. In 2017 summer camp, the children’s “ability to read accurately improved by 5%” as well as their “reading comprehension rate” went up by 2% (Simone, Hauptman, & Hasty, 2019) compared to their pre – camp assessments. As the program continued, the authors were able to identify its strength and weakness, and how to improve it for the next couple of years. The children’s reading comprehension rate has been increasing over the years largely due to their motivations and change of perception of themselves, as readers and writers to being more positive.

The generalized of the study proves that home and school communication on literacy helped improve children’s literacy achievement. By establishing trust, parents were able to share the literacy growth of their child from what they observed at home. For instance, one grandmother reported that she could not drive off from the summer camp until her granddaughter read her chosen book or a shared a story she wrote that day (Simone, Hauptman, & Hasty, 2019). Parents were more engaged and felt more relevant as a partner in their child’s literacy. The interpretations of the data were appropriate because the authors were able to incorporate parental input and not go the traditional route of remedial worksheets and language-controlled texts that do not necessary produce more confidant and motivated readers and writers. The children were able to connect real world experiences to literacy, to share concepts that normally took longer through a series of nonmeaningful worksheets. These authentic approaches help build a better literacy foundation for students who are sometimes overlooked or placed into intervention groups due to poor testing results.

The study provided updated information and resources of topics that can be used to help educators better foster a relationship between home and school. The program’s concepts of authentic literacy approaches should be incorporated in the state’s literacy plan rather than simply using the basel books that provided used throughout the school year. By empowering children and parents, they would be held accountable with their literacy development, as well as teachers being able to share supported practices that would help at home.

Works Cited

Simone, J., Hauptman, A., & Hasty, M. (2019). Better Together on Behalf of Our Children. International Literacy Association, 281-289.

Using Visuals to Teach Phonics: Sand, Pictures, and iPads

Amanda Gyemant

Min Mize

Abstract

Reading is an important skill for children to learn. Early reading skills such as phonics skills are a viable predictor of later reading skills such as word identification and reading comprehension. Lack of age-appropriate phonics skills can cause severe reading difficulties over time such as dyslexia. Given that a large proportion of students are visual learners, teachers are in need of using effective visual-based phonics lessons. To that end, this article presents examples of visual-based phonics activities using various mediums such as sand, pictures, graphic organizers, and iPads.

Using Visuals to Teach Phonics: Sand, Pictures, and iPads

Ms. Cho is an elementary special education teacher. In her classroom, there is a sweet girl, Esmeralda, who has shown reading difficulties. Esmeralda loves having lessons with Ms. Cho and doing small group as well as one-on-one instructions with her. When Ms. Cho mentions any information that Esmeralda has been already taught or has practiced, however, Esmeralda gets easily upset, seems to get overwhelmed, is about to cry. Ms. Cho has been desperately looking for fun ways to motivate Esmeralda and keep her engaged during her phonics lessons. After numerous tries and research, Ms. Cho has been using effective research-based instructional activities. First, we discuss how to implement visual-based phonics instructions for struggling readers like Esmeralda, and then we share benefits and challenges of the visual-based phonics training.

About 80% of students with learning disabilities have a reading-related disability (Lyon et al., 2001). The National Assessment of Educational Progress ([NAEP], 2019) reported that 32% of fourth graders are reading below grade level. If students are not reading on grade level by third grade, they are more likely to always struggle with reading and begin to struggle with other academic areas as well (Lesnick, George, Smithgall& Gwynne, 2010).

One of the five components of the reading process is phonics, which focuses on the individual phonemes (sounds) of a word. Students need to master the individual letter sounds before they can blend them and work on word recognition. Phonics is often defined as a fundamental skill that enables students to be aware of the relationships between printed letters and their corresponding sounds (Ehri et al., 2001; Lonigan, 2003). Because of its importance as a predictor of later reading skills such as word identification and reading comprehension (Ehri et al., 2001), lack of age-appropriate phonics can cause dyslexia (Pennington, van Orden, Smith, Green, & Haith, 1990; Schaars, Segers, & Verhoeven, 2017). Without being able to decode a word, students would skip the word or guess, but never actually learn the word. When students are able to decode a word and break it apart into the individual sounds, they need to know all of the individual sounds in order to figure out what the word it.

Phonics instruction is defined as teaching reading that focuses on the grapheme–phoneme correspondences by teaching students (e.g., how each single letter can be sound and how to blend the sounds together for a correct pronunciation of the word) (Bowers & Bowers, 2017). Also, it teaches the student to break up and decode each word and learn the individual sounds. Phonics instruction is beneficial and can help the students understand each letter sound and how to decode words.

Effective Phonics Instruction for Struggling Readers

Given the importance of establishing phonics skills for struggling readers’ later and higher-level reading skills (e.g., reading comprehension), teachers often include phonics lessons in their regular reading program. Students participate in phonics lessons and learn how to sound out print letters and words. In this way, when they read a book or a text, they are expected to apply their knowledge and to read each word by knowing its meaning. For students with reading difficulties and disabilities, more motivating and effective programs are needed as they relatively show lower interest and engagement during instruction (?odygowska, Ch??, & Samochowiec, 2017; Reeve, Jang, Carrell, Jeon, & Barch, 2004). Given the fact that the majority of the students are visual learners (Gangwer, 2009), it is evident that teachers should use more phonics lessons with visuals especially for their struggling learners.

Research suggest that visual based instruction combined with multisensory activities are effective for struggling learners to help them read letters and words (e.g., Henry, 2020; Macaruso, Hook, & McCabe, 2006; Morgan, 1995). Multisensory activities in phonics lessons include having students match natural speech sounds and print letters (i.e., auditory and visual matching) as well as tactile and/or kinesthetic activities.

There are several studies that found visuals helped struggling readers learn phonics (e.g., Cihon, Gardner, Morrison, & Paul, 2008; Nicholas, McKenzie, & Wells, 2017). The visuals can be used in various mediums such as teacher-delivered instruction, instructional materials (e.g., sand, whiteboard), or technology (e.g., laptops, tablets). Nicholas et al. used mobile applications that used picture cues to help struggling readers’ letter-sound association. They found that when students used the self-directed mobile application, its effects on the phonics skills are as effective as teacher-delivered instruction. The visual-based phonics lesson can be also delivered through a teacher modeling. Cihon et al. used teacher’s hand signs to teach struggling children letter-sound relations. The teacher hand signs could mimic some movements of lips, tongue, and throat.

In this article, we suggest several visual-based phonics activities using various mediums such as sand, pictures, graphic organizers, and iPads. This article is designed to explore the activities for phonics instruction for children with reading difficulties and disabilities. The purpose, however, is not to examine the importance, theories, or benefits of phonics instruction. Rather, the purpose of the article is to help those who teach phonics to struggling readers consider visual-based phonics activities and make good choices in supporting the struggling readers by modifying and expanding our example activities based on the strengths and needs of their own students.

Creating a Motivating Environment Using Visual-Based Phonics Activities

Hands-On Activity using Sand

There are many ways that teachers can use sand to teach phonics. First, teachers can use sand to see which letter sounds that students are struggling with. Students can use a list of the letters and letter sounds they missed after teacher had them write a letter on the sand. For example, Ms. Cho gets each pair a tray and pours some sand on the tray. She tells each student that after they have their list of sounds, they write it on the sand and each time they read each letter aloud (see Figure 1). The other way is giving students a quiz using sand. Ms. Cho writes 3-4 letters on the sand and have the students choose the letter that she sounded out. This approach allows her to provide immediate feedback. She gives them a praise when they give her a correct answer or a reward (e.g., iPad time, stickers) based on their preference. Also, students receive corrective feedback and additional opportunities to take the quiz following their incorrect answers.

Using sand provides a kinesthetic approach to learning letter sounds (Schlesinger, 2017). This helps students because it gives them another form of a learning style. Hearing the letter sounds and writing the letters in the sand at the same time helps reinforce learning because it engages students’ senses and helps them get engaged in learning.

Figure 1.

Focused Practice using Sand

After Esmeralda goes through each letter, she re-reads the passage again for three minutes. Her partner, who is a strong reader, marks all of the letter sounds they pronounce incorrectly and what sounds they make instead. Ms. Cho continues to walk around and monitor the groups and assist with forming the correct letter sounds when needed. Repeated reading helps students with their reading fluency. It helps them read the passage quickly and accurately. After a student realizes the sounds they missed, they should read more accurately the second time.

After Esmeralda is done reading, her partner tells her which letter sounds she missed again. The student marks which letter sounds they missed after the second time reading in their reading notebook. Ms. Cho informs the students that it is their responsibility to practice those letter sounds so that they can improve the next time. Ms. Cho also tells the students that she will help them as needed. The students turn in their notebooks to the teacher when they are done.

Picture Notebook

The students should keep a reading notebook and add to it over the year. Students can use this information to track their progress and graph it to see how well they have improved over the year. After the first student writes down all of their letter sounds, they put away their notebook. Then Ms. Cho informs the students that they will switch roles and the other student will now read. The pair switches roles and they work through steps four through eight with their reading passage. Ms. Cho continues to monitor and walk around to ensure that the groups are working well and doing what they are supposed to do. The student who is struggling with reading letter sounds like Esmeralda gets two chances to practice and be exposed to various letter sounds.

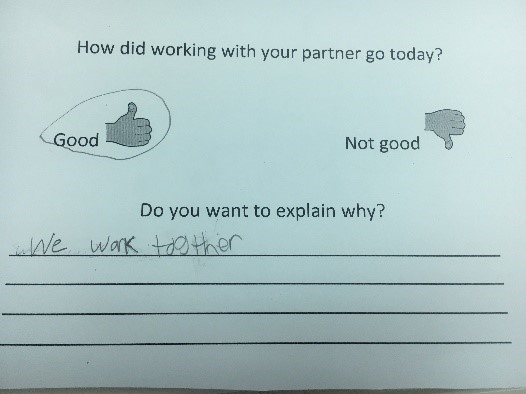

Once all of the students have read through their passage twice, written the letters in sand, and written them in their notebooks, Ms. Cho collects their notebooks so that she can see how many letter sounds students are missing. Ms. Cho has the students fill out an exit ticket (see Figure 2). The exit ticket is a survey of how well they worked with their partner and how much effort their partner put into the assignment. Ms. Cho collects these and make adjustments to the groups for next time if needed.

Figure 2.

Exit Ticket

Graphic Organizers

Letter sounds using graphic organizers can be used when Ms. Cho gives Esmeralda a graphic organizer and has her use it to learn unknown letter sounds in a reading passage. During tier three, for example, Ms. Cho works one on one with students who needs extra assistance to understand the letter sounds. Ms. Cho uses the following steps to help the students who are struggling. Ms. Cho is meeting with Esmeralda who is still struggling after the tier two instruction.

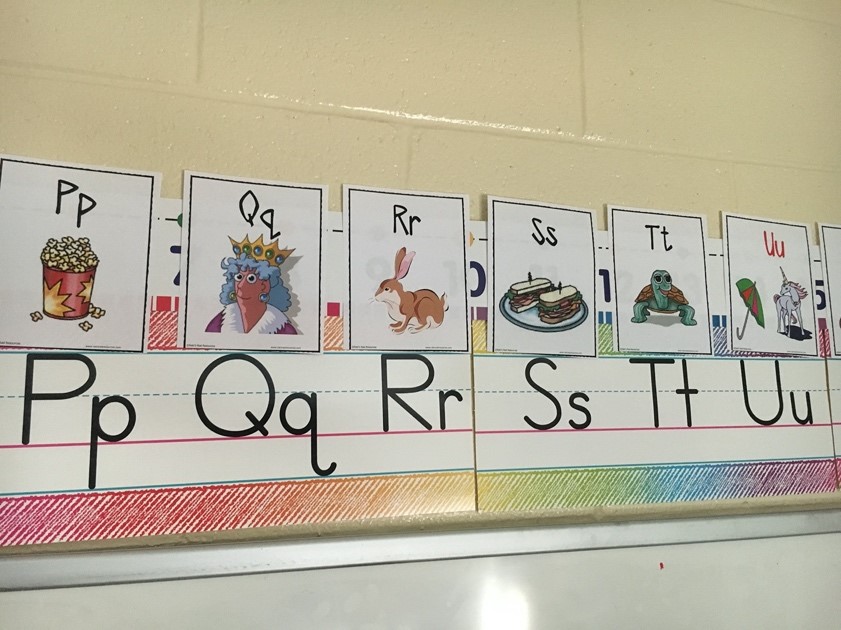

Ms. Cho uses explicit instruction to teach Esmeralda how to sound out each letter in a word by using a letter poster (see Figure 3). Ms. Cho starts by modeling to break apart each letter in a word. For example, she says the word, “dog” and then says each sound pausing after each sound. Then she says, “d-o-g-”. Then Ms. Cho says another word, for example, “cat” and has Esmeralda repeat it back to her. She says the first letter “c” and pauses and gestures to the students to have them say the second sound “a”. Ms. Cho provides positive reinforcement and corrective feedback if necessary. Then she says the final sound. Next, Ms. Cho writes down another word on the board and has Esmeralda say it out loud. Then she asks the students to break apart the word and say each sound in the word.

Figure 3.

Letter Cards

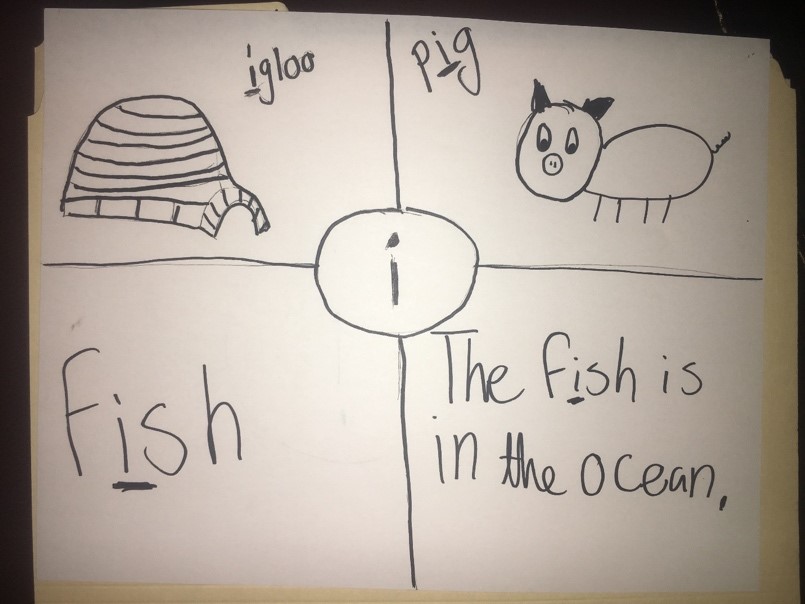

Ms. Cho reads a passage aloud to Esmeralda. Before she begins, she instructs her to follow along with her while she reads. She pauses after every fourth word to give her a chance to break up the word and identify each letter sound. Ms. Cho provides Esmeralda with a letter sound graphic organizer that focuses on a particular letter she was struggling with in the word. For example, for the word, “fish”. Esmeralda has a hard time with the letter sound /i/ so Ms. Cho instructs her to fill out the graphic organizer for the letter. The graphic organizer has the letter in the middle and the rest of the page divided into four sections. Two of the sections have pictures (igloo and pig) so that Esmeralda can see the sound that the letter makes. The other two sections have a spot where Esmeralda writes fish and then a sentence with the word in it. (See Figure 4). Esmeralda underlines the letter sound /i/ in each word and sentence. Graphic organizers provide a visual with letters, pictures, words, and sentences all in one place. It shows the letter sound in a variety of ways, which helps reinforce the learning of the word and the letter sound.

Figure 4.

Graphic Organizer

If Esmeralda does not say each sound in the word after Ms. Cho pauses and instructs her to, she prompts her by saying, “What sounds do you hear in that word?” If she says each sound, Ms. Cho uses positive reinforcement such as specific verbal praise to encourage her. For example, she says, “You did a good job saying all the sounds in that word correctly!”

If Esmeralda does not break apart each sound in the word after she asks her to, Ms. Cho uses a prompt fading least to most prompting hierarchy in order to get her to say that word. First, Ms. Cho points to the word she just read. Next, she re-reads the word for her. Then she says the first two sounds in the word and gestures for Esmeralda to say the remaining sounds. Finally, Ms. Cho models all the sounds in the word and request imitation from her.

After Esmeralda says each sound, even with prompting, Ms. Cho will provide positive reinforcement. For example, she will say, “You did a good job saying all the sounds in that word correctly!” or “You filled out the graphic organizer correctly, that looks so good!” Ms. Cho will continue reading through the passage and stopping after every fourth word in order to let Esmeralda break apart the word and say each sound. Ms. Cho will continue using the least to most prompting hierarchy and positive reinforcement to help her.

iPads

Using iPad to teach phonics to children with reading disabilities and difficulties is a viable option for several reasons. First, iPads allow them to learn phonics based on their own pace (Beschorner & Hutchison, 2013; Larabee, Burns, & McComas, 2014). Also, as children could easily lose their interest and focus, it can be very challenging for many teachers to teach them phonics; continuous audio and video effects of iPad applications can help younger students keep engaged. In addition, students need to pronounce unknown words by applying the principle of phonics that they learned, which requires repetitive practice. By using iPads, they are able to learn how to sound letters and how to apply phonics rules to unfamiliar words in a text.

Here are some ways that teachers can utilize iPads in teaching phonics based on the explicit instruction (Archer & Hughes, 2011). The first step is teaching students the difference between various letter sounds by modeling each sound. The modeling can be done in a combination of sounds from iPad and the teacher. The next step would be helping students learn the sounds that letters stand for. This step involves having students practice with the teacher using a letter card that is accompanied with a sound in the iPad application. During this step, students are asked to repeat after the sound provided by the iPad application, and they get feedback from either the iPad application or their teacher. To be familiar with the phonics principles, it requires repetitive practice (Mesmer, 2019; Oakland, Black, & Stanford, 1998). As many iPad applications include sound and visual effects, it helps keep students engaged in practicing same letter sounds multiple times. Also, teachers may want to use a game-based application during this step, which has been known to increase student motivation. The last step is independent practice where students practice by themselves while the progress is monitored by their teacher. The data are collected and analyzed to prepare for the upcoming instruction based on the students’ strengths and weaknesses in learning letter sounds and applying phonics principles.

In addition, there are many benefits that iPads can provide for more motivating and engaging literacy instruction. Research shows its portability, easiness of use, and customization functions (Almutlaq & Martella, 2018; Boyd, Hart Barnett, & More, 2015; Ozok, Benson, Chakraborty, & Norcio, 2008; Retalis, Paraskeva, Alexiou, Litou, Sbrini, & Limperaki, 2018). While many applications available in the application market give teachers several options, it is highlight challenging to find an application that is aligned the purpose of the instruction and needs of their students. Teachers are recommended to use a rubric that can assist them in finding the best application available based on the functions that they look for.

Benefits

There are multiple benefits to visual-based reading strategies discussed in this article. The first one is, it puts the responsibility of learning on the student. When the student takes responsibility for their learning, they will show more independence and more of a desire to learn, which will help focus their learning. These strategies are also engaging and provide hands-on opportunities to learn. When lessons are engaging and hands-on, students are required to pay more attention and be involved in the lesson, which helps them understand the content better. Another benefit is that the students get to help other students learn. Small groups and peer mediated learning enable students to work together on the same skill. Students can share different ideas, perspectives, and backgrounds with each other while working together. This collaboration can help students understand the material better and reinforce learning.

Visual-based small-group or peer-mediated learning can be effective for all students involved. Those who are slightly ahead are able to reinforce their learning by demonstrating mastery. Those who are slightly behind, are able to take control of their learning and hear from a new perspective, other than the teacher. A benefit of the one-on-one instruction is that the teacher is able to clearly explain the directions and work directly with the student. The teacher also provides a least to most prompting hierarchy, which promotes independence and ensures that the student will not become dependent on the prompt. The whole strategy provides opportunities for all various types of learning.

Challenges

Despite all the benefits, there are also a few challenges that can arise. The first challenge was pairing students to work with each other. No matter how well-behaved a class is, there are always going to be students who get off task or who do not hold each other accountable. The teacher will be walking around monitoring, however there is only so much he or she can see at once.

Another challenge is that one student will be trying to follow along with a reading passage that is above their instructional reading level. Even though they are just checking to see if students made the correct sound, it could become difficult and overwhelming for the student who is trying to follow. The teacher will remain in close proximity in order to help if needed, but the teacher will not be there the whole time. Students could ask a student in another group for help with the sound if they are unsure and the teacher is not near them at the time.

A challenge with the one-on-one instruction is that it is difficult to check to how independently a student can identify the letter sounds. When a student is given multiple prompts and a graphic organizer, it can be challenging to check for independence. The teacher can mark that the student got the letter sound correct, but they will have to indicate the amount and level of prompts the teacher used in order to help them get there. The teacher would have to give another independent assessment after the lesson to check for mastery of letter sounds and complete independence.

When it comes to the iPad-assisted phonics instruction, it might be challenging for teachers to choose a right application that meets criteria that s/he is looking for in an application. Teachers can evaluate some iPad applications using a rubric (Mize, Park, Schramm-Possinger, & Coleman, 2019; Ok, Kim, Kang, & Bryant, 2016) to be sure that the application has functions (e.g., audio, video, error correction, navigation, customization) that students can benefit from. It also might be difficult to ensure that students are staying on task when using iPads. Teachers can walk around a monitor the students on the iPads and seat them so that he or she can easily see what they are doing on their screens.

What to Do and What Not to Do

The visual-based phonics instruction can be helpful when teaching students how to read and look for individual sounds. However, in order for it to be successful, there are a couple of techniques that should be done and should not be done. When using peer tutoring, do not pair students who do not work well together. It is important during this step to think carefully and plan which students would be more successful working together. When using the least to most prompting technique, do not skip steps and give them the answer. Make sure that the prompts are being faded and only used when absolutely needed. When using the graphic organizer, do not make the students fill it out for every letter sound, only the ones they missed. This could cause the students to think of the graphic organizer as tedious, rather than helpful. Do use specific positive verbal praise after a student gets a right answer. This should be done immediately after they get the answer correctly. Do pause after each prompt and give the student a chance to respond during the use of the prompt hierarchy. This will give the student a chance to use the prompt before moving on to the most restrictive one. Do purposefully and thoughtfully leave out words for the students to fill in when modeling the skill.

References

Almutlaq, H., & Martella, R. C. (2018). Teaching elementary-aged students with autism spectrum disorder to give compliments using a social story delivered through an iPad application. International Journal of Special Education, 33(2), 482–492.

Archer, A. & Hughes, C. (2011). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. NY: Guilford Publications.

Beschorner, B. & Hutchison, A. (2013). iPads as a literacy teaching tool in early childhood. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 1(1), 16-24.

Bowers, J. S., & Bowers, P. N. (2017). Beyond phonics: The case for teaching children the logic of the English spelling system. Educational Psychologist, 52(2), 124–141.

Boyd, T. K., Hart Barnett, J. E., & More, C. M. (2015). Evaluating iPad technology for enhancing communication skills of children with autism spectrum disorders. Intervention in School & Clinic, 51(1), 19–27.

Cihon, T. M., Gardner, R., III, Morrison, D., & Paul, P. V. (2008). Using visual phonics as a strategic intervention to increase literacy behaviors for kindergarten participants at-risk for reading failure. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 5(3), 138–155.

Coyne, M. D., Oldham, A., Dougherty, S. M., Leonard, K., Koriakin, T., Gage, N. A., Burns, D., & Gillis, M. (2018). Evaluating the effects of supplemental reading intervention within an MTSS or RTI reading reform initiative using a regression discontinuity design. Exceptional Children, 84(4), 350–367.

Devonshire, V., Morris, P., & Fluck, M. (2013). Spelling and reading development: The effect of teaching children multiple levels of representation in their orthography. Learning and Instruction, 25, 85–94.

Duncan, L. G., Castro, S. L., Defior, S., Seymour, P. H. K., Baillie, S., Leybaert, J., … Serrano, F. (2013). Phonological development in relation to native language and literacy: Variations on a theme in six alphabetic orthographies. Cognition, 127(3), 398-419.

Dye, G. (2000). Graphic organizers to the rescue! Helping students link—and remember—information. Teaching Exceptional Children, 32, 72–76.

Ehri, L. C., Nunes, S. R., Willows, D. M., Schuster, B. V., Yaghoub?Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T. (2001). Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta?analysis. Reading research quarterly, 36, 250 – 287.

Gangwer, T. (2009). Visual impact, visual teaching: Using images to strengthen learning. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Henry, E. (2020). A Systematic Multisensory Phonics Intervention for Older Struggling Readers: Action Research Study. Networks: An Online Journal for Teacher Research, 22(1). doi.org/10.4148/2470-6353.1281

Larabee, K., Burns, M., & McComas, J. (2014). Effects of an iPad-supported phonics intervention on decoding performance and time on-task. Journal of Behavioral Education, 23(4), 449–469.

Lerner, J. W. (1993). Learning disabilities: Theories, diagnosis, and teaching strategies. Dallas, TX: Houghton Mifflin.

Lesnick, J, George, R., Smithgall, C., & Gwynne, J. (2010). Reading on grade level in third grade: How is it related to high school performance and college enrollment? Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

?odygowska, E., Ch??, M., & Samochowiec, A. (2017). Academic motivation in children with dyslexia. Journal of Educational Research, 110(5), 575–580.

Lonigan, C. J. (2003). Development and promotion of emergent literacy skills in preschool children at-risk of reading difficulties. In B. Foorman (Ed.), Preventing and Remediating Reading Difficulties: Bringing Science to Scale (pp. 23 – 50). Timonium, MD: York Press.

Lopez, J., & Campoverde, J. (2018). Development of Reading Comprehension with Graphic Organizers for Students with Dyslexia. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 8(2), 105–114.

Lyon, G. R., Fletcher, J. M., Shaywitz, S. E., Shaywitz, B. A., Torgesen, J. K., Wood, F. B., Schulte, A., & Olson, R. (2001). Rethinking learning disabilities. In C. E. Finn, Jr., A. J. Rotherham, & C. R. Hokanson, Jr. (Eds.), Rethinking special education for a new century (pp. 259-287). Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Foundation.

Macaruso, P., Hook, P. E., & McCabe, R. (2006). The efficacy of computer-based supplementary phonics programs for advancing reading skills in at-risk elementary students. Journal of Research in Reading, 29(2), 162–172.

Mesmer, H. (2019). Letter lessons and first words: Phonics foundations that work. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Mize, M., Park, Y., Schramm-Possinger, M., & Coleman, M. B. (2019). Developing a rubric for evaluating reading applications for learners with reading difficulties. Intervention in School and Clinic, 55(3), 145-153.

Morgan, K. B. (1995). Creative phonics: a meaning-oriented reading program. Intervention in School & Clinic, 30, 287–291.

National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2019). NAEP 2018 trends in academic progress. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Nicholas, M., McKenzie, S., & Wells, M. A. (2017). Using Digital Devices in a First Year Classroom: A Focus on the Design and Use of Phonics Software Applications. Journal of Education and Learning, 6(1), 267–282.

Oakland, T., Black, J. L., & Stanford, G. (1998). An evaluation of the dyslexia training program: a multisensory method for promoting reading in students with reading disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 31, 140–147.

Ok, M., Kim, M., Kang, E., & Bryant, B. R. (2016). How to find good apps: An evaluation rubric for instructional apps for teaching students with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 51(4), 244–252.

Ozok, A., Benson, D., Chakraborty, J., & Norcio, A. (2008). A comparative study between tablet and laptop PCs: User satisfaction and preferences. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24(3), 329-352.

Retalis, S., Paraskeva, F., Alexiou, A., Litou, Z., Sbrini, T., & Limperaki, Y. (2018) Leveraging the 1:1 iPad approach for enhanced learning in the classroom. Educational media international, 55(3), 213-230.

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barch, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasing teachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and emotion, 28(2), 147-169.

Schaars, M. M. H., Segers, E., & Verhoeven, L. (2017). Word decoding development during phonics instruction in children at risk for dyslexia. Dyslexia, 23(2), 141–160.

Schlesinger, N. W., & Gray, S. (2017) The impact of multisensory instruction on learning letter names and sounds, word reading, and spelling. Ann. of Dyslexia, 67, 219–225.

Spilles, M., Hagen, T., & Hennemann, T. (2019) Playing the good behavior game during a peer-tutoring intervention: Effects on behavior and reading fluency of tutors and tutees with behavioral problems. Insights into Learning Disabilities, 16(1), 59-77.

Stricklin, K. (2011) Hands-on reciprocal teaching: A comprehension technique. Reading Teacher, 64(8), 620-625.

The Curious Case of Fragile X Syndrome

Anthony Ruggiero

Introduction and History

In today’s society, children and adults alike are greatly impacted by exceptionalities that affect their daily living. One of those exceptionalities is Fragile X Syndrome or FXS. Although the history of this classification is short, researchers have conducted several studies in order to acquire various information regarding its causes. Researchers have discovered that FXS, caused by genetics, can greatly impact a person’s cognitive and physical development. Despite FXS being irreversible, researchers have also tested various practices, such as assistive technology and medication, in order to tackle its adverse effects and improve the lives of those living with it.

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) is a classification that has only been studied for the past 75 years. Research began in 1943, when geneticists, J. Purdon Martin and Julia Bell, investigated a family with eleven male members who were diagnosed with “mental retardation”. They conducted their study through observing the family member’s behavior and through interview. For example, Martin and Bell observed and described the male family members as having been brought up by “intelligent”, but still have the mental capacities of three or four-year-old children (2018). Martin and Bell further included that their vocabulary was exceptionally limited, mostly “inarticulate.” During their interviews with the male family members, they observed that they could answer very simple questions such as “‘yes ” or ”no,” and that they could identify their names, as well as the names of objects. However, Martin and Bell also noted that none of them could make a complete sentence (2018). One of the male family members, whom Martin and Bell labeled “V 54,” when asked what work he did (carrying coal), after long a long pause, was only able to say the word “black.” Martin and Bell also studied two “psychotic members” of the family. They described “V 50” as paranoid and destructive, whereas “V 48” they described as a “schizoid.” They posed that each of the members demonstrated dementia-like symptoms and linked their cognitive disorders to an X-linked inheritance. Due to their early findings, Fragile X Syndrome is also known as Martin-Bell Syndrome (Background to Fragile X, 2010).

After years of inattention, further knowledge was acquired of FXS by scientist Herbert Lobs. Through Martin and Bell’s work, Lobs developed an interest, and in 1969, he identified the altered X chromosome that is associated in individuals with FXS. Prior to his discovery, Lobs developed a chromosomal test for FXS individuals during a 1966 case study. During this case study, Lobs observed four men and two women, who were classified then as “mentally retarded.” As he was conducting his study, Lobs noted that the chromosomes appeared abnormal. Lobs observed that one of the arms of the X chromosome was limited which gave it the appearance of being broken. By seeing this “broken” chromosome, Martin-Bell Syndrome became known also as Fragile X Syndrome (Background to Fragile X, 2010). Further studies conducted by scientist Grant Sutherland in 1977 confirmed Lobs’s findings. Additionally, Sutherland was also able to identify where the site was within the body in order to study the chromosomes of a specific patient (Claypool, Laniyan, Singh, & Wolf, 2009). As a result, more studies of FXS were able to be conducted.

In 1985, researcher Stephanie Sherman and her team decided to study the inheritance patterns of FXS patients. During this time, researchers had not conducted studies on people who carried the fragile gene but were unaffected (Claypool, Laniyan, Singh, & Wolf, 2009). Sherman and her team were able to show that patients’ parents, who had them later in life, were largely affected. For instance, the daughter of an unexpected male carrier has a higher percent chance of have an affected child than the mother of an unaffected male carrier (2009). Sherman and her team posed that this was the characteristic that had changed on the X chromosome over two generations. This would later be coined as the “Sherman Paradox” and is highly important in understanding the cause of Fragile X Syndrome.

Further studies were conducted in 1991. Researchers discovered FMR1, otherwise known as Fragile X Mental retardation 1 gene. Researchers reported that when the FMR1 gene is “shut off,” it prevents the FMR1 from creating the protein needed for important brain development (Bailey, n.d.). The lack of the FMR1 protein Fragile X is the most common cause of inherited mental impairment ranging from learning disabilities to severe intellectual disabilities and autism.

Definition and Cause

According to Cafasso (2016), Fragile X Syndrome is defined as “an inherited genetic disease passed down from parents to children that causes intellectual and developmental disabilities.” Fragile X syndrome is caused by change or mutation in a gene on the X chromosome (What is Fragile X Syndrome, 2014). Chromosomes are a collection of genes that are passed from generation to generation. Most individuals have 46 chromosomes, two of which are sex chromosomes. In females, there are two X chromosomes, while males have one X and one Y. Genes are given names to identify them and the gene responsible for Fragile X syndrome is called the FMR1 gene (2014). The mutation is in the DNA on the X chromosome. The gene appears in several forms that are defined by the number of repeats of a pattern of DNA called CGG repeats. Individuals with fewer than 45 CGG repeats have a normal gene. Individuals with 55-200 CGG repeats have a “permutation”, which is an unstable version of the FMR1 gene that can expand in future generations. Individuals with over 200 repeats have a “full mutation” which causes Fragile X Syndrome. The FMR1 gene produces a vital protein called FMRP. When the FMR1 gene is shut off by the full mutation, the individual does not make FMRP. The lack of this specific protein causes Fragile X syndrome (2016).

Fragile X syndrome is one of a group of conditions called nucleotide repeat disorders (2014). A common feature of these conditions is that the gene can change sizes over generations, becoming unstable, and thus the conditions may occur more frequently or with greater severity in subsequent generations. These conditions are often caused by a gene change that begins with a permutation and then expands to a full mutation in subsequent generations (2014).

Approximately 1 in every 8,000 females and 1 in every 4,000 males carry the Fragile X permutation (2016). Fragile X permutations are defined as having 55 to less than 200 CGG repeats and can be present in both males and females. In males with a permutation, the permutation usually does not expand to a full mutation when passed on to daughters. A male never passes on the Fragile X gene to his sons, since males pass their Y-chromosomes to their sons. A female carrier of a permutation is at increased risk of passing on a larger version of the mutation to her children. As the size of the permutation increases, there is an increased possibility that a child will receive the full mutation (2014).

Fragile X is an “X-linked” condition, which means that the FMR1 gene is located on the X chromosome. Since women have two X chromosomes, women with either a permutation or a full mutation have a fifty percent chance of passing on the X with the CGG expansion in each pregnancy (2016). If she carries a permutation, and it is passed on to either males or females, it can remain a permutation or it can become a full mutation. In many X-linked conditions, only males who inherit the abnormal gene are affected; however, in Fragile X syndrome, females can also be affected (2014). In other X-linked conditions, all males who carry the gene are affected; however, in Fragile X syndrome, unaffected males can have a permutation and have no symptoms of Fragile X syndrome. Males with the permutation will pass it on to all of their daughters and none of their sons (2014).

Characteristics

Fragile X syndrome is the most common inherited cause of mental impairment. The majority of males with Fragile X syndrome will have a significant intellectual disability. The spectrum ranges from learning disabilities to severe cognitive impairment and autism. In addition, males have a variety of physical and behavioral characteristics and problems. However, no male has all of these features. Enlarged ears and a long face with prominent chin are common. Connective tissue problems may include ear infections, mitral valve prolapse, flat feet, hyper flexible fingers and joints, and a variety of skeletal problems. Behavioral characteristics in males include attention deficit disorders, speech and language disturbances, hand biting, hand flapping, autistic behaviors, poor eye contact, and unusual responses to various tactile, auditory or visual stimuli. Some children with Fragile X syndrome also develop seizures.

In boys with fragile X syndrome, research indicated that there was steady cognitive growth in IQ until mid-adolescence. However, according to research, development tends to decrease around this time and the gap between individuals with fragile X syndrome and their typically developing peers widens. There is also some evidence that around half of individuals may show a decline in adaptive communication skills from around 10 years of age and it is possible that this is associated with increases in social anxiety in adolescence.

The characteristics seen in males can also be seen in females, though females often have milder intellectual disability and a milder presentation of the behavioral or physical features. About a third of the females have a significant intellectual disability. Others may have more moderate or mild learning difficulties. Similarly, the physical and behavioral characteristics are often expressed to a lesser degree.

Prognosis

As a result their permanent condition, individuals living with Fragile X Syndrome face challenges. People with the syndrome struggle with the very skills that might help them cope with change, something researchers refer to as “adaptive behavior.” According to Wright (2014), skills, from getting dressed to being able to talk easily with others, allow people to function independently. Most people learn these skills beginning in childhood improve, as they get older. But, people with Fragile X Syndrome may not learn as many adaptive skills, and thus are dependent on caregivers. A Pediatrics study (2014) followed 275 children with Fragile X Syndrome and 225 children without Fragile X Syndrome, all ranging from 2 to 18 years of age, every two to four years. The researchers assessed their adaptive skills using the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, a questionnaire filled out by parents or caregivers (2014). Overall, the children with fragile X syndrome had lower scores for adaptive behavior than the other children.

Girls with the syndrome become worse at communicating as they get older, but their social and daily living skills stay stable. In contrast, boys with fragile X syndrome have lower adaptive behavior scores for communicating, socializing and daily living skills as they age. The reason for this gender difference is unclear, but it might be that the syndrome generally less affects girls (Wright, 2014). The study did note, that, “interestingly,” boys with FXS were more social than girls with the disability. In adolescents, individuals exhibited social anxiety. However, it was noted that, despite the anxiety, individuals were able to develop better social skills, thus showing, that despite their challenges, individuals with FXS can succeed in daily living.

Best Practice Treatments and Conclusion

In order to improve their daily functions, researchers and educators have implemented different practices. Within the classroom, implementing visuals and assistive technology is helpful for students with Fragile X Syndrome. Both work as aides to elevate the stress within the classroom. During a 2012 study by the Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium, an adolescent, Toby, was observed before and after implementing visual aide and assistive technology. Tyler performed an action known as stemming to stimulate his senses (2012). Tyler would use a pencil, pen, cell phone, any object he can find that is intriguing and shake it right in front of his face, surprisingly never hitting his face. Tyler stemmed because he was upset and needed to calm down, or he was bored. Though stemming naturally relaxed Tyler, it interfered with his work and easily distracted him (2012). A method to reduce Tyler’s stemming process and keep him on task was a visual schedule. By giving Tyler a visual schedule to see what was expected of him, researchers noted that his anxiety and boredom levels were reduced.

Another helpful practice that was also utilized within the study was assistive technology. Though Tyler could verbally communicate to get his point across, his speech is was described as, “unclear and repetitive” (2012). Additionally, Tyler also demonstrated a lack of social-emotional reciprocity. For example, when Tyler greeted someone he would automatically tell them, “You okay, you okay….you fine, you fine.” One way researchers helped Tyler with his unclear, repetitive speech was through using a mid-tech device known as VOCA, or Voice Output Communication Assistance. This device allowed Tyler to communicate by just the click of a button. Researchers again noted an improvement of Tyler’s social activity, as he was able to communicate his needs with other people.

Another treatment for individuals living with Fragile X Syndrome is medication. For example, according to Harris (2010), a drug called, Novartis, was highly effective in treating individuals with FXA. According to a study conducted in 2010, researchers measured a range of behaviors such as hyperactivity, repetitive motions, social withdraw, and inappropriate speech. They gave one set of patients the drug and another a placebo, and after a few weeks switched treatments. The results of the trial demonstrated that the behavior habits of the patients with FXS improved. Parents of these patients were elated and described the experience as, “euphoric.” The antipsychotic, medication, risperidone, has also been used to treat individuals with FXS (Daniely, 2015). A randomized placebo-controlled trial of risperidone in children demonstrated significant behavioral improvement. However, adverse effects such as weight gain, increased appetite, fatigue, drowsiness, dizziness, and drooling, were also present at the end of the trial (2015). Despite these effects, medication has proven to be effective in helping those Fragile X Syndrome.

Fragile X Sydrome impacts individuals throughout their lifetime, specially their social and physical development. During this study, I learned many things that could be beneficial during my teaching career. Prior to this research, I had not encountered Fragile X Syndrome within my classroom. Conducting this research reaffirmed for me the importance of visualizing the classroom; a method that I had always felt was significant in providing aide to students. Furthermore, I also learned the importance of assistive technology. Assistive technology can be used for a variety of resources within the classroom, for in this instance, helping students communicate effectively. I am curious to the additional impact of medication and feel additional research should be conducted due to their inconclusive effects. Overall, this paper has given me further tools to improving my classroom for my students with different learning needs.

Citations

Bell, J., & Martin, J. (2018). Retrieved from https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/jnnp/6/3-4/154.full

Fragile X Syndrome: Condition Information. (2016). Retrieved from, www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/fragilex/conditioninfo

Fragile X Clinical & Research Consortium, (2012). Retrieved from fragilex.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Educational-Guideines-for-Fragile-X-Syndrome-General.pdf

Harris, G. (2010). Promise Seen in Drug for Retardation Syndrome. Retrieved from www.nytimes.com/2010/04/30/health/research/30fragile.html

Wright (2014). What Is Fragile X Syndrome? Retrieved from fragile-x-clinic.med.umich.edu/what-is-fragile-x-syndrome.

Book Review: How to Win Friends and Influence People

Massiel N. Rodriguez

Dale Carnegie was an influential American writer and lecturer, who developed courses in salesmanship, public speaking and self-improvement in general. His most popular book “How to Win Friends and Influence People” is widely considered to be one of the most important self-improvement books when it comes to interpersonal relationships. Over fifteen million copies have been sold all over the world since it was written in 1936. It is considered so influential that it has been translated in over 40 languages and it is still relevant today.

Purpose and thesis of the book:

The purpose of the book is to make people more effective at interpersonal relationship through personal and professional development. The book shows how people can change in many ways to become more adept at managing complex and different day to day situations when dealing with people. The Thesis of the book is that you can positively influence people in order for them to see your point of view, and eventually adopting it without offending them or making them defensive. A key component to achieve this is to do your best to see things from the other person’s perspective.

Main Themes:

The main themes of this book all complement one another, being receptive of the perspective of others, making people give value to your influence, and showing interest in people. The book argues that being receptive of other people’s perspective will make them “lower their guard” and even make them believe that you are genuinely interested in their opinion. By showing genuine interest you make people give value to your influence as they believe that you are not attacking them or trying to convert them to your way of thinking. Finally, by showing interest in people they will see that you are consistently open and trying to improve the relationship shared by both and genuinely trying to have a positive influence in them. These themes illustrate the need to act in a certain way even if you disagree or dislike the other person.

Key quotes from the book:

“One of the fundamental keys to successful human relations is understanding that other people may be totally wrong, but they don’t think so.”

“To be interesting, be interested.”

“You can’t win an argument. You can’t because if you lose it, you lose it; and if you win it, you lose it.”

“Remember that a person’s name is to that person the sweetest and most important sound in any language.”

“Talk to someone about themselves and they’ll listen for hours.”

Weak and Strong Points:

The Strong points of the book are how detailed and specific the recommendations are. For example, being genuinely interested in other people “If you break it down, you should listen 75% and only speak 25% of the time”. Another example is to begin an argument in common ground and ease your way into the difficult subjects because if we begin in polarizing ground, we will not be able to recover.

The weak points are that this book sometimes can come off as extremely optimistic, especially in the techniques the book suggest you use. Also, many of the techniques can seem very manipulative as you try to solely understand or seem a specific way to elicit a specific response from people. In chapter seven you learn to “let the other person fell like the idea is his or hers” which obviously can be read as a way to manipulate someone.

Comparing this book against others leadership books: