Table of Contents

- Special Education Legal Alert. By Perry A. Zirkel

- Collaboration and Advocacy between Parents and Teachers: A Literary Review. By Denise Cruz

- Barriers to Involvement in the Special Education Process for Families of Culturally Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds: A Review of Literature. By Christopher Salerno

- Visual Supports to Improve Outcomes for Culturally Diverse Students with ASD. By Valeria Yllades, Jennifer B. Ganz & Ching-Yi Liao

- Culturize Every Student. Every Day. Whatever It Takes: A Book Review. By Rebekah Caballero

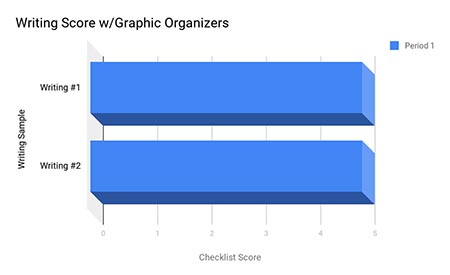

- The Use of Graphic Organizers and Other Tools to Aid in the Writing Process. By Stephanie Fletcher

- U.S. Department of Education Announces Initiative to Address the Inappropriate Use of Restraint and Seclusion to Protect Children with Disabilities, Ensure Compliance with Federal Laws

- Teacher – Parent Collaboration for an Inclusive Classroom: Success for Every Child: A Research Critique. By Samantha Ashley Forrest

- Book Review: Lead Like a Pirate. By Emily Glick

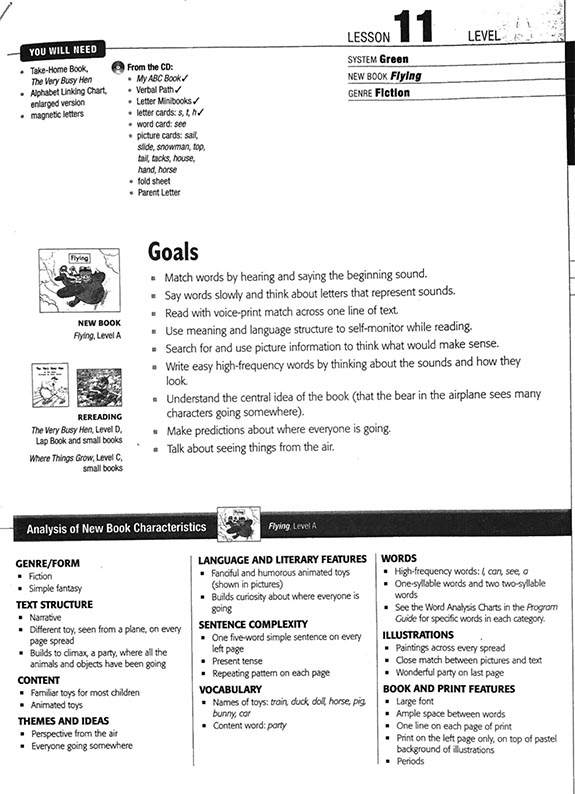

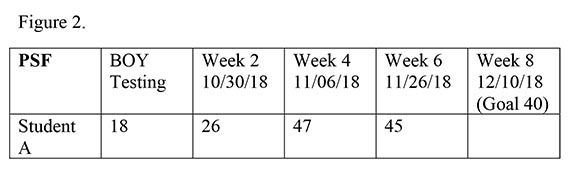

- Action Research: The Effectiveness of Leveled Literacy Intervention (LLI) in Early Elementary Grades. By Mallory Goodson

- Repeated Reading in the Middle School Setting. By Hannah Grim

- An Academic Review of: The Mind of the Leader: How to Lead Yourself, Your People, and Your Organization for Extraordinary Results. By Aimie Young

- Buzz from the Hub

- Latest Job Postings Posted on NASET

- Acknowledgements

- Download a PDF Version of This Issue

By Perry A. Zirkel

© January 2019

This month’s update concerns two issues that were subject to recent court decisions and are of practical significance: (a) contingent IEPs for students in third-party placements, such as Medicaid-provided residential treatment facilities; and (b) restrictions on parental communications to district personnel based on a previous pattern of excessive or intimidating e-mails, calls, and/or visits.

|

In L.T. v. North Penn School District (2018), a federal district court in Pennsylvania addressed the extent, if any, of the IDEA obligations of the school district of residence to a child who is may be discharged from a residential treatment facility (RTF) that is outside of the district’s boundaries. In this case, a 16-year-old with severe autism was in an RTF located in another Pennsylvania school district and at the expense of state Medicaid based on medical necessity. The parents received a notice that the student would be discharged due to a determination that the placement was no longer medically necessary. The district of residence took the position that it had no obligation to develop an IEP for the student until he re-enrolled upon discharge from the residential facility.

|

|

|

First, the court cited a previous federal court ruling in Pennsylvania (I.H. v. Cumberland Valley School District, 2012), which required a contingent IEP in an arguably similar cyber-school situation based on (1) the difference between FAPE and an IEP, and (2) the remedial purposes of the IDEA. |

The court explained that (1) although overlapping, an IEP is merely “an offer of FAPE”; it is a prospective proposal for as compared with the actual delivery of FAPE, and (2) the remedial purpose of the IDEA outweighs the possibly futile purpose of returning the child for a day to establish actual residency or leaving the child in legal limbo. |

|

Next, applying these two factors to the circumstances of this case, the court ruled that the resident district has the obligation under the IDEA to develop a contingent IEP for a child in an RTF beyond the district’s boundaries. |

This ruling is not likely limited to RTFs or this jurisdiction because I.H. was beyond this circumstance and it cited case law beyond Pennsylvania. Where this contingent-IEP ruling does extend, so does the accompanying obligation for evaluation, which was not at issue in this case. |

|

The reference to a “contingent” IEP is a potential source of confusion. Although the RTF’s notice of discharge prompted the action, the real trigger appears to be the parents’ request, and the contingency ultimately is that the IEP is a proposal conditional upon the parents’ agreeing to the IEP or challenging it as not meeting the FAPE requirements.

|

In this case, all the parents actually won was the right to have a due process hearing to determine whether the IEP provided FAPE (in the LRE), because (1) the district had gone beyond what it had regarded as legally required by developing an IEP, (2) the proposed placement was at the district’s high school, and (3) when the parents originally filed for due process, the hearing officer had granted the district’s dismissal motion. |

|

For the separate but similar issue of the respective but overlapping obligations under the IDEA of the district of location and the district of residence for parental private placements, see Perry A. Zirkel, Legal Obligations to Students with Disabilities in Private Schools, 351 Educ. L. Rep. 688 (2018), which is available as a free download at perryzirkel.com. |

|

|

A recent cluster of cases illustrate the courts’ position on school district communication protocols that limit, but do not prohibit, interactions from parents with disabilities in response to a previous pattern of disruptiveness. Although these unofficially published federal district court decisions are of limited precedential weight, they illustrate the various legal bases that the parents have asserted to challenge these restrictions and the relatively consistent outer boundary that the resulting rulings have demarcated.

|

|

|

One basis for parental challenge is the IDEA. In Forest Grove School District (2018), a federal district court in Oregon ruled that the successive limitations that the school placed on the e-mails of a parent of a child with autism, which were based on their continuing excessive amount and increasingly aggressive tone, did not significantly deny the their opportunity for participation in the IEP process. |

The district first required the parents’ e-mails to go only to the case manager, then limiting these communications to one weekly e-mail to the case manager, and ultimately only to the district’s attorney in response to the e-mails’ increased excessiveness and aggressiveness. These restrictions did not affect the parents’ telephone and in-person access. The court used the IDEA’s FAPE standard for parents’ rights—the opportunity for meaningful participation. |

|

First Amendment expression and state civil rights legislation are other potential bases. In L.F. v. Lake Washington School District #414 (2018), a federal district court in Washington State ruled that the successive restrictions that the school district placed on in-person meetings with the divorced father of a child with disabilities in response to his continuing pattern of angry and hostile encounters with district personnel did not violate the freedom of expression under the First Amendment or the anti-discrimination provision of the state civil rights act in relation to sex and marital status. |

The district successively limited all parental communications first to one biweekly meeting with three designated school representatives; second, in response to the parent’s continued violations, to one meeting per month; and finally, upon further violations, to e-mail only. The restrictions did not apply to the parent’s access to the child’s school records, the activities open to parents, and any emergency situations. For the First Amendment, the communication limits were based on the means, not the content of expression, and they met the resulting test of being reasonable and viewpoint-neutral. For the state civil rights statute, the parent did not show sex or marital discrimination. |

|

Another possible basis consists of Section 504 and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). In the aforementioned L.F. decision, the court rejected the parent’s Section 504 retaliation claim based on the lack of a causal link between the protected activity of the parent’s lawsuit and the district’s adverse action of the communication restrictions. In Lagervall v. Missoula County Public Schools (2018), a federal district court in Montana provided a more comprehensive analysis in response to the more specific pertinent provisions of the ADA to reach the same overall outcome. |

Section 504 and, more specifically, the ADA prohibit disability-based retaliation. Both the L.F. and Lagervall decisions concluded that the parent failed to show a causal link between any protected activity and the adverse action; the likely reasoning was that the restrictions applied to this pattern of parental communications regardless of whether they were on behalf of a child with disabilities. This pair of statutes also prohibits disability-based coercion, but, as Lagervall ruled, the requisite causal link again was fatally missing. Finally, the ADA specifically requires “equally effective communication,” but the Lagervall court found no violation in the specific case circumstances. |

|

The bottom line is for school districts to make sure that any limitations on communications from parents with disabilities (a) have a legitimate, nondiscriminatory basis, and (b) are tailored to the level of disruptiveness without being all-encompassing or absolute in terms of access and interaction. |

|

By Denise Cruz

Abstract

Collaboration and advocacy are two areas where both parents and teachers agree that more can be done. Two possible ways in which this can be accomplished are by having better communication between parents and teachers as well as better understanding of the different cultural views that parents and teachers may have. Acknowledging that improvement is needed and seeking assistance in these areas is the first step in achieving better collaboration and advocacy for all parties involved.

Parents want what they believe is best for their children. Teachers want what they believe is best for their students. However, getting both to agree on what is best educationally can be a challenge. This is especially true when the child has a disability. Some of these challenges are: (a) apprehension on the part of the parent, (b) miscommunication from both the parent and the teacher, (c) language barriers, (d) cultural barriers, and (e) disagreements on goals. Each of these variables when looked at separately can be justified or explained. However, when the collective significance of these variables is considered, it often creates the “perfect storm” for not being able to “do what is best for the child”, and often negatively impacts collaborative efforts Collaboration is an integral part of ensuring that the child receives the best possible support both at home and at school. Collaboration requires knowledge on the part of the parent, the student and the teachers. From knowledge comes advocacy and from advocacy comes reaching a “middle ground”, the best possible support for all parties involved. In order to achieve this middle ground, all parties must agree to work together on a common goal and give each other the needed support to bring out the best in all (plug the reference here, just the authors’ names and year of publication).

In order to create a common goal, one must have as much information about the subject as possible. In education; teachers, parents, caregivers, doctors, and students should be included in the gathering of such information. Unfortunately, this process has been plagued with obstacles from the very beginning. However, with the passing of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1975 (IDEA), families began the slow process of educating themselves on their rights as well as on the rights of their children. School systems began the process of working with parents and other professionals in order to provide the best possible education for all students.

Research has shown how the knowledge that parents and students bring to the table is just as valuable as the knowledge that educators and doctors convey. According to (Just add authors’ last names and year of publication) collaboration between parents and teachers is one of the most important factors to increase student success. “Parent advocacy and collaboration activities became a clear factor influencing children and youth’s social and academic success within the school setting.” (Shultz et al, 2016, must add page number for direct quotes). However, reaching this point has proven to be difficult. Teachers’ “…negative stereotypes of parents…” (p. # for direct quotes) as well as parents’ distrust has created an adversarial relationship (Wischonowiski and Cianca, 2012). That is why “rewriting the script” is such an important concept. Programs like the partnership between The Advocacy Center and the St. John Fisher College in Rochester, N.Y. are vital in order to bring about change. Their goal was to bring forth positive stories from families so that educators and other families could see that a positive relationship was achieved by supporting each other (Wischonowiski and Cianca, 2012).

This partnership required a thirteen-week commitment on the part of all the participants. The program included different types of families with different backgrounds and ethnicities, as well as children with different types of disabilities. The program began when The Advocacy Center approached a professor at St. John Fisher College about speaking to parents on what to expect on curriculum and academic outcomes. The professor then turned it into a project where his students would work with actual families and thus help to build a positive relationship, were both parties would be able to achieve a common goal: student success.

The project included 25 college students, who were divided into groups of 5 and were paired with a family from The Advocacy Center. The program was a semester long project where the group would work with the family in learning how to work best together. First the group would go over the IEP and write an introductory letter to the parents, and the parents would then arrange a meeting where all parties would meet. For the next six-weeks, the groups and the parents met and discussed the different issues that the parents encountered at the schools. At the end of the six weeks, the parents shared their views on the meetings and what they hoped to accomplish. Subsequently, the groups would research the different concerns that parents brought to the meetings, and gave recommendations on how to minimize these concerns. In the end (week thirteen), “…collaboration and rapport between the parents and teachers by identifying problems and seeking solutions together to achieve better outcomes for students.” had been achieved (Wischonowiski and Cianca, 2012, add page number for direct quotes).

Other factors that do not allow for collaboration are the misunderstanding and misconceptions on the part of both the parent and the teacher. One of these r factors relates to culture. As of 2007, about 26% of school-aged students in the United Stated spoke another language other than English at home (Shin and Kiminski, 2010). This has created a communication barrier between parents, students, and teachers. “Culturally diverse students’ distinctive set of cultural values, beliefs and norms is often incongruous with the cultural norms and behaviors of schools.” (Irvine, 2012, add page number for direct quotes). This phenomenon has often created misunderstandings, , as teachers sometimes fail to recognize certain cultural behaviors. For example, students not raising their hands to answer questions but instead shouting the answer, can be considered disruptive and uncontrollable; therefore, the student may be referred to special services and thus creating a mistrust from parents (Irvine, 2012). Using stereotypes like race, educational level, marital status and social class can also create misconceptions by automatically believing that the student will be an underachiever and/or have emotional or behavioral issues. These negative stereotypes can keep the student from academically advancing and can result in the student being wrongly referred for Special Education services (Irvine, 2012).

Irvine (2012) recommended the use of Culturally Responsive Pedagogy or CRP in order to better prepare special education teachers and avoid common misunderstandings and misconceptions. CRP follows four basic principles: 1) developing caring relationships with students while maintaining high expectations, 2) engaging and motivating students, 3) selecting and effectively using learning resources, and 4) promoting and learning from family and community engagement (Irvine 2012). Irvine suggested that in order to achieve CRP both relevant course work and hands-on experiences are necessary (Irvine, 2012). “Culturally responsive learning activities build on the lived experiences of diverse learners and supported instructional outcomes.” (Irvine, 2012, add page number for direct quotes) should increase the likelihood that educators will apply more culturally responsive pedagogy. Irvine (2012) also suggested the use of cooperative team learning strategies and flexible grouping, for a more effective diverse learner as well as culturally diverse materials. Lastly, Irvine (2012) recommended increased communication with parents on students’ progress, including motivation and preferences in order to build a more cohesive learning environment, and a better communication method with parents.

Communication as well as collaboration is one of the key elements that parents across the board state as the number one reason for satisfaction with their child’s education (Shultz et. al, 2016). “Unfortunately, research indicates education professionals often do not view parents as equal partners.” (Shultz et. al, 2016, add page number for direct quotes). This “attitude” makes communication as well as collaboration extremely difficult. Therefore, changing the script once more becomes vital, and advocacy is one of the best ways to reach this goal. Even though, advocacy in education is sometimes viewed as a negative word, it can be a very rewarding and positive experience. According to Ridnouer (year of publication, and page number for direct quote) “An advocate is a person who supports or promotes the interest of another, and that is what a teacher is doing when he or she works to engage students and their parents as partners in a positive, learning-focused classroom community”.

This new venture where parents and teachers work together can begin with a simple invitation from the teacher. This invitation can be to the school’s open house, a special school-wide activity, a classroom activity, or to the child’s Individual Educational Plan (IEP). Notably, the IEP is usually one of the most controversial times where both parties are advocating for what they each believe is the best for the child. Unfortunately, “…research suggests families who participate in traditional IEP meetings have expressed their primary role included listening and answering questions.” (Childre & Chambers, 2005, add page number for direct quotes) instead of collaborating. Again, changing the script is reccommended. To accomplish such goals, Shultz et. al (2016), looked into teacher’s perceptions, specifically teacher’s perceptions of parents with children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Shultz et. al (2016), also focused on how parents support children with ASD in the classroom setting by using advocacy and collaboration.

Shultz et. al (2016), conducted the research in a southeastern rural school district and invited teachers who taught students with ASD to participate. T hirty-four teachers from elementary, middle and high school participated in the research. The participants included special education teachers, general education teachers, and special areas teachers. The teachers were divided into focus groups of no more than eight and met over the course of a year for no more than an hour at a time. The facilitators were either a university faculty member or a graduate assistant who followed a script to ensure fidelity as well as maintaining group focus. Each focus group was given a fictional case-study in which they were to analyze the case and answer questions related to parent advocacy and collaboration. The meetings were taped and later transcribed. The results showed that teachers felt that parents where either over involved or under involved, but that in either case parents needed assistance in accepting the child’s diagnosis and were in need of learning better advocacy strategies .

These meetings brought about how to positively encourage collaboration and advocacy between parents and teachers.. Some of the recommendations made by the teachers were for them to share more information with parents through booklets, help parents find ways to teach social skills to the child at home by possibly working with siblings and other family members, and to teach their child how to self-advocate (Schultz et. at, 2016). Shutlz et al (2016), in his discussion went further into detail on how this could be accomplished. Shultz et. al (2016) suggested that teachers “Recognized a continuum of parent involvement” in which both parents and teachers recognized each other’s short cummings and worked together to reach a consensus. One way to achieve this was through Making Action Plans (MAPS) (Vandercook, York, & Forest, 1989) were parents provide input on how to develop the goals for the coming IEP. Another suggestion was to “Provide extra support during diagnostic process” in which not only the diagnosis was given but what roles each of the professionals working with the student has as well as resources within both the school and the community (Shultz et. al, 2016, add page numbers for direct quotes). Next, was how to support parent in their advocacy role. This was one of the most challenging as sometimes parents can be unrealistic or have no idea what to advocate for. For this reason, Shultz et. al (2016) suggests “careful conversations” in which teachers guide parents through the services and help them on how to advocate for the child as well as how to teach the child how to advocate for themselves. Lastly, Shultz et. al (2016) suggests to “Target key areas for ongoing collaboration” like social skills which ASD students usually lack. According to Shultz et. al (2016, add page number for direct quotes), teachers recognize that the curriculum is not always built to accommodate time for social skill building and therefore, parents need to work on it at home. One of the ways to accomplish this is through Circle of Friends Model (Taylor, 1997) in which siblings or other family members become the ASD child role model on social skills. The model suggest that the family member take the child on outings with their circle of friends to allow the ASD child to witness proper social interaction and at the same time the non-ASD child to guide the ASD child through the process of social interaction.

Teachers and parents can guide each other in the academic process that the child will be navigating throughout their academic experiences. By doing this, the hope is that a new script is written, were both parents and teachers can collaborate and create common goals, where the student can move forward and be successful. Reaching this goal is often hard and has an extremely long journey; as communication and misconceptions will continue to riddle the process. If all parties continue to practice the script, progress can be made in improving communication and dispelling the misconceptions that are brought to the process.

References

Amy Childre, & Cynthia R. Chambers. (2005). Family perceptions of student centered planning and IEP meetings. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 40(3), 217-233. Retrieved from https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/stable/23879717

G. Taylor. (1997). Community building in schools: Developing a ‘circle of friends.’. Educational and Child Psychology, , 45-50.

Hibel, J., & Jasper, A. D. (2012). Delayed special education placement for learning disabilities among children of immigrants. Social Forces, 91(2), 503-529. doi:10.1093/sf/sos092

Irvine, J. J. (2012). Complex relationships between multicultural education and special education. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(4), 268-274. doi:10.1177/0022487112447113

Jacob Hibel, George Farkas, & Paul L. Morgan. (2010). Who is placed into special education? Sociology of Education, 83(4), 312-332. doi:10.1177/0038040710383518

Michael W. Wishchnowski, & Marie Cianca. (2012). Reading a new script for working with parents.

Ridnouer, K. (2011). Everyday engagement. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Shin, H. B., & Kominski, R. (2010). Language use in the united states, 2007. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau.

Tia R Schultz, Melissa A Sreckovic, Harriet Able, & Tamira White. (2016). Parent-teacher collaboration: Teacher perceptions of what is needed to support students with ASD in the inclusive classroom. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51(4), 344-354. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.fiu.edu/docview/1843276153

Vandercook, T., York, J., & Forest, M. (1989). The McGill action planning system (MAPS): A strategy for building the vision. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 14(3), 205-215. doi:10.1177/154079698901400306

By Christopher Salerno

Abstract

Throughout the process of identification, evaluation, placement, and continued support of students with disabilities, the involvement and engagement of the parents is a vital aspect that will have long term effects on the student’s academic progress. Under the guidelines of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004), it is required that parents are given the opportunity to be active participants in the decision-making process and the development of a student’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP). However, when working with families that come from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, several barriers may present themselves that effect involvement in the process including language, availability of parents to participate, and diverse cultural views. It falls on the shoulders of the special education teachers and school staff to accommodate to the individual needs and to respect the individual cultural aspects of the learners and their families using a variety of best practices and strategies.

The vital role that the family plays in the outcomes of students with disabilities is one that can favorably sway the pendulum of support and success. Public schools are becoming more diverse over time as evidenced by the increasing number of students with disabilities (SWD) from families of culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) backgrounds being served by special education programs. The families of these students each have a unique situation, as well as needs and barriers that can impact their education. The term family is often used in a flexible manner when working with CLD students. The family unit in some cultures may only include the parents and children, while in other cultures it may extend to grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, or any other blood relative. Based on the individual dynamics, a ‘parent’ may be a guardian, family may include close friends that have no blood or marital connection, or the student may have been sent to live in the United States with a relative, while their immediate family remained in their nation of origin. Families may face unique hardships such as supporting multiple family members financially, both at home and in their nation of origin; they may be recent immigrants, illegal immigrants, or may be migrant workers. With such a wide range of individual situations, being culturally responsive and accepting of the family’s participation, and encouraging it as well in the special education process, is vital to the student’s progress.

Throughout the process of identification, evaluation, placement, and continued support of SWD, the involvement and engagement of the parents is a vital aspect that will have long term effects on the student’s academic progress. Under the guidelines of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004), it is required that parents are given the opportunity to be active participants in the decision-making process and the development of a student’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP). However, when working with families that come from CLD backgrounds, several barriers may present themselves that effect involvement in the process including language, availability of parents to participate, and diverse cultural views. When not identified and effectively supported, these barriers may make families feel marginalized and can obstruct the development of a collaborative relationship between parents and school staff.

Language can be a major barrier for any parent involved in their child’s special education process. The support for communicating with parents and families in their home language is one that schools are required to provide (U.S. Department of Education, 2015). Ensuring parental understanding of items discussed during all parts of a special education meeting is imperative, as any errors in communication or translation can lead to confusion and misinterpretation. It is highly recommended that special education team members build a trusting collaborative relationship with the parents as the process begins, promoting more open communication that will support the learning outcomes of the student (More, Hart, & Cheatham, 2013). In some cultures, disabilities are perceived as a source of shame and are something not to be discussed outside of immediate family (Pang, 2011). Accordingly, having interpretation support that is effective and properly conveys the information presented to the parents is a key factor. It is considered a best practice to utilize an interpreter that understands special education terminology, is sensitive to cultural nuances, and acts in a manner that is professional and respectful of all parties involved (Lo, 2012; More, Hart, & Cheatham, 2013; Pang, 2011). Additionally, providing copies of documents that are translated into the parents’ home language ensures that they are given proper access to records and can make informed decisions.

Aside from the obvious difficulties that parents may face if they speak a different language from that of the school staff, a larger issue concerns the use of technical language during meetings and in documentation. For professionals outside of the field of special education, the use of various acronyms, initialisms, and specialized terminology can be extremely confusing. When parents are presented with the complex terminology that they are often unfamiliar with, it can cause a divide in the home-school relationship or further alienate the parents if a rapport has not developed. It is considered a best practice to avoid using acronyms and complex terminology when meeting with parents and to present information in plain language to support their understanding and ensure translators are knowledgeable enough to accurately translate the meaning of specific terminology and explain details to families in an effective manner (Pang 2011). When working with the family and special education team during a meeting, it is helpful to check for understanding and summarize key points as the conference progresses, and thus providing multiple opportunities to clarify or allow for questions from all parties involved (More, Hart, & Cheatham, 2013). However, this must be done in a respectful manner, as to not appear condescending to the parents’ knowledge or abilities.

A further area of concern with regards to language and communication is the procedural safeguards which provide guidelines for parental rights, ensure accountability, and lay out the method for resolving disputes that potentially arise when engaging in any IEP process. A 2012 study by Mandic, Rudd, Hehir and Acevedo-Garcia, found that in an analysis of the procedural safeguard documents available on the department of education websites for all 50 states and the District of Columbia:

- 55% of the documents scored at a college reading level range,

- 39% were considered to be at a graduate or professional reading level,

- 6% were scored at a high school level

According to the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy, 22% of adults in the United States read at a below basic level and 33% read at a basic level. This difficulty is compounded for CLD families where their literacy skills in English may be minimal. This disparity in reading levels of adults and the readability of the procedural safeguards can be disparaging to many parents regardless to how willing they are to engage in the process. Mandic et al. (2012) argue that if the purpose of the procedural safeguards is to provide parents with concise information to facilitate effective home-school partnerships in developing the IEP, then it must be developed using plain language that parents can clearly understand and make informed decisions on the part of their child.

When engaging families during the IEP process, encouraging their participation is a key component that is required under IDEA. However, this can become a major barrier that can have a significant effect on the student and the parent. When working with families from CLD backgrounds, parental availability to attend meetings can become a substantial barrier that professionals may face throughout the special education process. In some cases, the barrier to attending meetings may be attributed to work schedules of the parents. Parents from CLD backgrounds may work hourly wage jobs that do not provide paid personal leave time and where missing several hours from their work schedule can cause a major financial hardship (Murray, Finigan-Carr, Jones, Copeland-Linder, Haynie, & Cheng, 2014). Some families may have members working multiple jobs to support extended family locally or even from their nation of origin. The members of the special education team need to be sensitive to the individual situations of each student’s families and attempt to accommodate as much as possible when scheduling meetings (Pang, 2011). In a study by Murray, et al. (2014), it was determined that the barriers related to socioeconomic status affect the time a parent has to participate in school meetings, as well as negatively impact their socio-emotional state by adding additional stressors. Accommodating to the individual situations can provide relief to the parents and aid in fostering a stronger collaborative relationship. Professionals can arrange meetings at times that are more convenient for the family, provide support for transportation needs, hold teleconferences, or utilize web-based video conferences in effort to promote parental involvement (Fishman & Nickerson, 2014; Murray, et al., 2014). Furthermore, encouraging parental involvement beyond the context of special education meetings can have a multifold effect on student achievement by shaping the student’s attitude toward their education, improving parent-child communication, and developing positive academic expectations (Fishman & Nickerson, 2014).

When working with families from CLD backgrounds, the aspect of respecting and accommodating to varying cultural views on special education is one that professionals face daily. Engaging families in a manner that promotes effective collaboration and sharing of information can be a difficult task when the professional may be unaware of how their actions and mannerisms can be misinterpreted by the families of students. The protocol of meetings, such as seating arrangements, access to quality translators, team members arriving on time to conferences, using respectful communication during pre-conference communications, and recognition of the parents as valued members of the process; can affect their willingness and comfort in participating throughout the special education process. Further, preconceptions of the capabilities of the parents to act as meaningful members of the special education team can affect the mood of meetings and the overall relationship that develops through the process.

Some families, view their role in the development of their child’s education plan as cursory and believe that their feedback is not needed or welcomed. In some cultures, the teacher is seen as a highly respected professional that is not to be questioned and thus conflict with them should be avoided (Lee, Rocco Dillon, French, & Kim, 2018). In these situations, the parents may feel that their questions may be a sign of disrespect. For other cultures the converse occurs, the parents feel they must question each component of the process to ensure the teacher has the child’s best interest in mind, and are not just going through the motions that are required by the government. In the myriad of cultural views and expectations of the special education process, the role of being culturally responsive falls on the teacher. According to research by Rossetti, Sauer, Bui, and Ou (2017) teachers should develop a practice of cultural self-reflection, examining their own beliefs and cultural views, then they can identify their personal habits that may be counterproductive to building rapport with the families of their students. The teacher and team members need to communicate with the family, and explore their cultural views on education overall, on the needs of individuals with disabilities, as well as identify their expectations and goals for their child. Engaging parents and families in a manner that focuses on their concerns for their child, and uses it to build the foundation of the student’s IEP, will likely solidify their role as a stakeholder in the process. The families of students with disabilities that come from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds face a variety of challenges while supporting their child’s needs including language barriers, socioeconomic difficulties, and cultural responsiveness. It falls on the shoulders of the special education teachers and school staff to accommodate to the individual needs and to respect the individual cultural aspects of the learners and their families using a variety of best practices and strategies.

References

Fishman, C., & Nickerson, A. (2014). Motivations for Involvement: A Preliminary Investigation of Parents of Students with Disabilities. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 24(2), 523–535.

Goldman, S. E., & Burke, M. M. (2017). The Effectiveness of Interventions to Increase Parent Involvement in Special Education: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Exceptionality,25(2), 97-115. doi:10.1080/09362835.2016.1196444

Lo, L. (2012). Demystifying the IEP Process for Diverse Parents of Children with Disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 44(3), 14–20.

Mandic, C. G., Rudd, R., Hehir, T., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2012). Readability of Special Education Procedural Safeguards. Journal of Special Education, 45(4), 195–203.

More, C. M., Hart, J. E., & Cheatham, G. A. (2013). Language Interpretation for Diverse Families: Considerations for Special Education Teachers. Intervention in School & Clinic, 49(2), 113–120.

Murray, K. W., Finigan-Carr, N., Jones, V., Copeland-Linder, N., Haynie, D. L., & Cheng, T. L. (2014). Barriers and Facilitators to School-Based Parent Involvement for Parents of Urban Public Middle School Students. SAGE Open, 4(4). doi:10.1177/2158244014558030

Pang, Yanhui. (2011). Barriers and Solutions in Involving Culturally Linguistically Diverse Families in the IFSP/IEP Process. Making Connections: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Cultural Diversity, 42–51.

Rossetti, Z., Sauer, J. S., Bui, O., & Ou, S. (2017). Developing Collaborative Partnerships with Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Families During the IEP Process. Teaching Exceptional Children, 49(5), 328–338. doi.org/10.1177/0040059916680103

Seo Hee Lee, Rocco Dillon, S., French, R., & Kyungjin Kim. (2018). Advocacy for Immigrant Parents of Children with Disabilities. Palaestra, 32(2), 23–28. Retrieved from https://https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=130206299&site=ehost-live&scope=site

U.S. Department of Education (2015). Information for Limited English Proficient (LEP) Parents and Guardians and for Schools and School Districts that Communicate with Them, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Department of Education (2003). National Assessment of Adult Literacy, 2003 [Data file]. Available from National Center for Education Statistics Web site, nces.ed.gov/naal/

By Valeria Yllades, Jennifer B. Ganz & Ching-Yi Liao

Abstract

Gilberto is a young immigrant child with autism spectrum disorder who is growing up in a Mexican household. He often has trouble understanding his peers and teachers who speak English. With the help of the school, he is adjusting to a new culture, learning a new language, and working on educational outcomes. The example stated above illustrate issues related to conflicting language and culture between school and home contexts. Practical supports and interventions to address language and cultural barriers, for individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) whose families are English Language Learners (ELLs), will be discussed in this article.The purpose of this paper is to draw from the evidence bases on interventions for children from bilingual families and intervention for children with ASD. Future recommendations are described to help bridge the gap between bilingual families and educators working with children with ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, English Language Learners

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disability that impacts social communication interactions (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, n.d.). It also includes restrictive, repetitive, and stereotypical behaviors (DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Currently, there is a growing number of children with ASD in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). In addition, there has been an increase of children identified in the U.S. as bilingual or English Language Learners (ELLs). Bilingualism is the ability to speak two languages and ELLs are individuals whose first language is not English, but who are living in English-majority communities and are learning some English (Klingner, & Soltero-Gonzalez, 2009). ELLs are the fastest-growing student population in the country, growing 60% in the last decade, as compared with 7% growth of the general student population (Grantmakers for Education, 2013).

Due to the rising rates of bilingual individuals and of individuals diagnosed with ASD, it is likely practitioners will work with this population during their career (Lund, Kohlmeier, & Durán, 2017). It is crucial that practitioners and caregivers have access to effective interventions to ameliorate language and communication barriers for this population. Furthermore, high-quality professionals are critical for this growing population (Lund, Kohlmeier, & Durán, 2017). Currently, educators are suggesting to parents not to speak two languages at home. Research shows language exposure in the home of two or more languages does not affect language development for children with ASD (Lund, Kohlmeier, & Durán, 2017). Practitioners suggesting to parents to speak a second language should carefully make such decisions as it can have negative repercussions on the family and child with ASD. It can lead to stress on the parent if they are not fluent in the language, further isolation for the child with ASD, and limit social interactions with family members. Early intervention that incorporates appropriate and culturally responsive communication instruction are recommended (Vesely, 2013).

Visual supports provide children with ASD environmental structure and predictability, which helps them to be more successful in learning and communicating (Cohen, & Sloan, 2007). This is particularly true for bilingual children with ASD, as they often have difficulty understanding content because they have deficits in attending skills or experience language barriers. Pictures, objects, written words in their home and community languages, or drawings may help children with ASD who are ELLs function better in different environments (Hodgdon, 1995). This article provides recommendations with regard to visually based communication strategies for educators or caregivers who work or live with individuals with ASD from culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) backgrounds. The following discusses how to the literature on research-based practices can inform implementation at home or at school.

Why it Works and Benefits

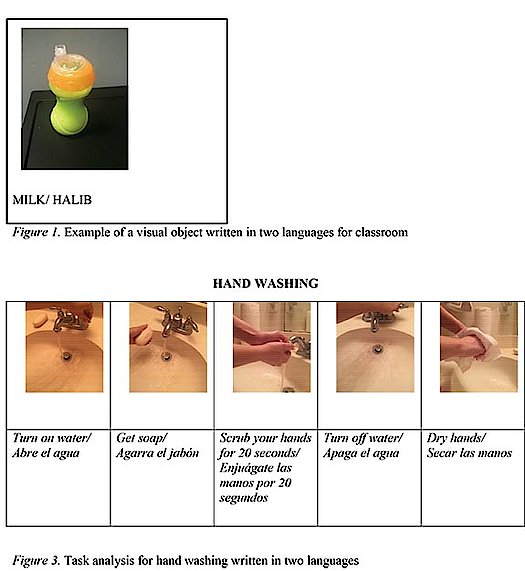

Visual supports are graphic and pictorial representations of stimuli that enhance comprehension of language and learning (Meadan, et. al., 20011). They can be beneficial tools for teaching communication skills to bilingual individuals with ASD (Fahim, 2014). Visual supports simplify communication for the practitioner while providing a tangible model for learners to appropriately express needs and wants. This will allow the opportunity for the individual to meaningfully make choices in his or her environment while communicating effectively (Meadan, et. al., 2011). The practitioner will provide information in a way that is easier to understand for learners who have a difficult time processing auditory words, who come from different cultural backgrounds, and who may not understand social contexts around them. It helps learners make sense of their environments, predict scheduled events, comprehend expectations placed on them, and anticipate changes made throughout the day or to routines (Dettmer, Simpson, Myles, & Ganz, 2000). The use of visual supports is a practical strategy that has been demonstrated to have positive effects on individuals with ASD, educators, and caregivers (Meadan, et. al., 2011). For example, a four-year-old child with ASD from Saudi Arabia, who spoke only Arabic was introduced to a school environment in the U.S. He did not know any English, so they printed out words in Arabic to display in the classroom. If the child requested milk (haleeb), the therapist would then give the item to him while saying, “milk, you asked for milk.” This is critical for bilingual learners with ASD, helps maintain engagementfor learners with and without ASD (Yamanashi, 2016).

Visual Supports and Instructional Strategies

Visual supports and associated instructional strategies are discussed in detail along with various complementary strategies that are used for successful implementation. First, this article describes particular strategies that can be used to teach learners how to use and understand the selected visual supports. We will expand on visual supports, the use of modeling, types of prompting procedures, fading, and reinforcement.

Instructional Strategies for Teaching Visual Supports

- Modeling or imitation are effective prompting procedures to help teach a skill to individuals with ASD (Rao & Gagie, 2006). There are two forms of modeling. Verbal modeling requires the practitioner to say exactly what they want the learner to say and the individual will imitate. (e.g. the practitioner: “Story time is next”, the child repeats after practitioner: “Story time is next”). Physical modeling is the use of showing the learner through specific movements that you want them to imitate (e.g. tracing with a pencil).

- Prompts can be either verbal, gestural, partially (by the wrist or elbow) or full prompt (by using hand over hand). Verbal prompts include giving the instruction to the learner (e.g. “It is time to work”). Physical prompts are those that include assistance to complete an activity or to transition between activities (Dettmer, Simpson, Myles, & Ganz, 2000). For example, providing physical prompt by assisting the learner using hand over hand to finish the work. Gestural prompts include pointing to the activity (e.g. pointing to the work).

- Gradually fade your verbal instructions from continuous to intermittent. Reduce prompting once you start to see the child become independent (Banda, 2009).

- Reinforcement is used after the individual engages in the targeted response. (e.g. high fives, smiles, saying, “Good job!”, pat on the back, tickles). Every individual is unique and reinforcement should be considered according to his or her wants and needs. These items or activities should also be age appropriate. If not pair the item they are interested in or activity with novel items or activities. (e.g. a 7 year old child playing with a baby play cube could be presented with a puzzle as the practitioner models how to play and reinforcers the child when they imitate).

Descriptions of Types of Visual Supports

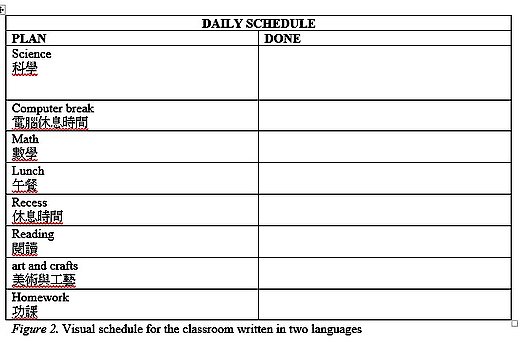

Visual Schedules. Visual schedules are a form of visual supports that could aid in comprehension of novel topics or expectations as a model and the preparedness of transitioning between activities (Meadan, et. al., 2011). Visual schedules, or across-activity schedules, are pictures, written words, or photographs that describe a series of activities to help understand upcoming events in a daily routine (Rao & Gagie, 2006). This is particularly important for learners from diverse backgrounds that might have difficulty understanding cues that indicate a transition time given by a practitioner in a classroom. With the help of visual schedules the learner then knows what to expect, which may lead to smoother transitions (Cohen & Sloan, 2007). Practitioners can use these in any setting where the child is struggling the most. Several studies have found support for the use of visual schedules with learners with ASD (Banda, Grimmett, & Hart, 2009; Rao & Gagie, 2006; Meadan, et. al., 2011). These may be particularly useful for those who have communication deficits or come from a diverse background (Fahim, 2014). Visual schedules have been demonstrated to a) successfully teach young children with ASD to transition between activities such as in Rao & Gagie (2006); b) improving a range of behaviors including communication skills (National Research Council, 2001); c) help decrease challenging behavior (Dettmer, Simpson, Myles, & Ganz, 2000), and d) help in the area of academics (Banda, 2009). Below are instructions on how to use a visual schedule in your classroom.

- A visual schedule is presented in a place that the child can see and the practitioner can gothrough with them as transition to different activities.

- First take a pictureof the different steps that will be included in the schedule.

- Print the photographs in a sequence to indicate the order they should follow (Meadan, et. al., 2011).

- Next, guide the individual to the schedule and prompt them when it is time for the next activity while showing them or pointing the pictures. Do this for every different activity and before transitioning so that they anticipate what is to happen next.

Look at figure 1 for more examples.

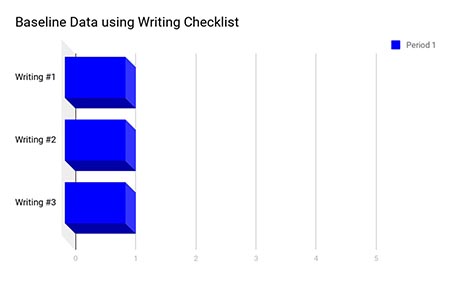

Tasks Analysis. Visual schedules, sometimes called within-activity schedules, may also be used to break down a task into discrete steps, by the use of a task analysis (Banda, 2009). Task analysis strategies have been used for young children and adults for learning how to perform different tasks by breaking them down into manageable components (Test, et. al., 1990). This procedure help children complete challenging activities in their daily lives independently. Using a task analysis in the form of a mini schedule, steps of self-help (e.g., shoe tying, tooth brushing), or other tasks may be displayed on a visual schedule. This strategy could be a tool to help with a diverse learner without the need to rely on auditory processing (Fahim, 2014). Below are ways to select the types of symbols for a CLD child with ASD.

- Collaborate with parents and other professionals who work with the child on items or activities that the child prefers.

- Language usage should be discussed and recommendations for language preference should be based on the individual case.

- Gather information about what the child can and cannot have.

- Come up with realistic and measurable goals that the practitioner can document to observe progress.

Once goals and materials have been gathered, use the task analysis as you would the visual schedule. Refer to the bullets above for more detail.

For example, upon group collaboration with the parents, it was decided that Devan a 5 year old with ASD who is from Nigeria would work on following instructions in the classroom. Devan is learning to hang his backpack upon arrival to classroom. The educator would place the discrete steps in a place that is visible for the student and preferably around the area where he will conduct the task. The discrete steps would serve as an aid to supplement verbal or gestural instruction. Use prompting procedures, reinforcement, and gradually fade as he reaches independence.

Linguistically and Culturally Responsive Adaptations in Implementation

Cultural Backgrounds and Activity Considerations for the Use of Visual Supports

In order to select appropriate use of visual supports based on culturally responsive activities, it is crucial to get to know the family (Meadan, Ostrosky, Triplett, Michna, & Fettig, 2011; Rao & Gagie, 2006). Knowing the family and their belief system can allow the practitioner to form build rapport with the families and to better understand the decision making process experienced by parents (Klingner & Soltero-Gonzalez, 2009; Matuszny et al., 2007). Concepts such as eye contact, asking questions, or joint attention could be viewed differently depending on cultural background. For example, in some cultures, direct eye contact with elders or women is considered inappropriate for children, while in other cultures, it would be considered rude or inappropriate to not look at a speaker (Wallis & Pinto-Martin, 2008). Eye contact is a common goal for children with ASD, as in the example earlier with Hayato, a young boy from Japan with ASD. Additionally, practitioners might work with a family in which the child with ASD is expected to complete certain tasks at home, such as household chores. Knowing this, the practitioner could determine communication needs and goals to address within natural contexts. How families view disability may also impact the type of supports needed for individuals. Cultural sensitivity is an important approach because it can affect planning and how well parents accept interventions and target skills to be taught; parent buy-in is a critical aspect in consideration of likelihood of maintaining use of new skills and evidence-based practices (Matuszny et al., 2007; Vesely, 2013).

These recommendations are to build and support collaborative relationships from families. The following strategies help teachers get to know their families’ priorities and backgrounds.

- Ask questions about the languages spoken at home and what languages the caregivers are comfortable speaking. Questions regarding cultural norms and family culture are also important to establish appropriate supports (Matuszny et al., 2007). Questions may include what language(s) are spoken at different times of the day, such as mealtime or play.

- Practitioners should listen to and clarify the information given by caregivers and respect their decisions or answers, which may be different from the culture of that practitioner, while giving their professional opinion for the learners needs (Matuszny et al., 2007).

- Practitioners could get to know the family through home visits, interviews, and periodically checking in with parents.

- Educators should avoid stereotyping and to get to know each family to encourage the development of relationships between school and home.

The above-mentioned activities can provide opportunities to teach and perform communication skills in home using the communication mode that is appropriate for the learner’s needs. It can also inform the practitioner regarding what communication modes may be most useful for the children. Suggest using visual schedules and verbal prompts in the language that is most comfortable speaking that they understand in order to eliminate dependency and promote independence while reducing language barriers.

Provide Visual Supports in Both Languages Using a Functional Communication Mode

Consider using multimodal ways of communicating such as an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), photos, drawings, written words, sign language, gestures, and speech. Many children with ASD have difficulty using speech and ELLs have difficulty with English; therefore, it is crucial to find a functional and alternative ways to communicate with others to access reinforcement (Fahim, 2014). The item or activity that are being presented will most likely be available at home, where items, such as the child requesting a banana, will be readily available. Use all opportunities in the home, school, or clinical setting to increase communication for the child in either language. The practitioner is not advised to communicate in a language they don’t speak fluently, but they would want to reinforce the child for every opportunity they communicate in either language they use.

Use visual supports while talking in the language that is most comfortable to the practitioner while accepting words the practitioner understands from the learner. Especially if it is an item or activity that the child requests frequently. For instance, if a child says “carro” and he is reaching for the car, the practitioner would say, “you asked for the car, here is the car”, while handing them the car. If a visual schedule is used with the child during school, then the words in both languages should be written under the photos or drawings to enhance the child’s understanding of both languages and promote the use of the same vocabulary across service providers and caregivers (Fahim, 2014). Written visual supports and instruction in both languages will enhance receptive and expressive communication as a result of constant pairing of spoken words with corresponding objects or other visual cues. Using the same or similar visual in every environment will help with consistency and generalization of the skills.

When teaching new vocabulary or introducing a new visual aid, make sure to implement consistently in all environments if possible. Consistency is key for developing and establishing behaviors; this will help the child build independence, feel confident in the skills they acquire, while learning new skills. It also allows them to practice the skills in a novel environment so they are successful in multiple situations.

Scenarios

Mateo was a three-year-old boy with ASD and complex communication needs, who had significantly delayed receptive and expressive skills upon registering in the school setting. His parents were asked what languages they spoke and they confirmed that they spoke their native language, Spanish, at home. The practitioner asked the parents if there was anything that motivated him to speak. They mentioned he would ask for trampoline and food a majority of the time. After asking a couple more questions regarding their home activities, the practitioner developed a treatment plan that included learning additional vocabulary to use to make requests and planned use of reinforcement to provide contingent access to the desired items when Mateo used word approximations. The child used AAC supports for break, the restroom, and mealtime while providing the word in both languages. Upon saying the name of or providing a picture for the preferred or needed item or activity, he would be praised and given the item or activities immediately. This approach increased the chances that he would use speech or other communication modes, such as AAC, to obtain these items and activities.

Sheng was a 5-year-old boy who had complex communication needs; he comes from a family that spoke Mandarin at home. His parents mentioned that he had never spoken and they mostly communicated with him in Mandarin. Sheng’s parents also indicated that he typically pointed to items to communicate his wants and needs and that he often cried to get what he wanted. Through collaboration with family members, the teacher decided to use pictures with Sheng.Every time he gave the picture of the item to the teacher, the teacher would give him the desired item and praised Eli for using his picture to communicate (e.g., “great asking with your picture”). The PECS pictures contained Mandarin and English words, which helped him make approximations in both languages. He has been able to communicate using the PECS effectively and is also making vocal sounds along with giving the card to the teacher. This is an effective way of using visual supports and language, as well as working with the family to practice this at home and in school.

Mohammed was an 8-year-old boy who had complex communication needs. His mom noted that she understood his gestures and gave him whatever he reached for. Upon talking to his teachers, his mom requested an SGD to communicate with his family in a more acceptable manner. They used a mobile device provided by the school to download the program and added a lanyard so Mohammed could carry the Ipad across his torso easily. When he reached for an item at home, mom would block Mike from getting it and would find the picture and written English and Arabic words for the item on the Ipad. Then, she would prompt him by leading his hand to tap the picture and the Ipad would produce the Arabic word associated with it. She would repeat the word in Arabic and praised him while giving him the item. She repeated this several times until he began making requests. Once she saw that Mohammed was using his Ipad to ask for items or activities consistently, she would only model how to tap the correct picture or correct him when he selected the wrong one. Once he did not need the model and was selecting it independently and consistently, she faded and would only point, or gesture, when he reached for items or wanted an activity and praised him when he did it himself. The school also used the SGD with Mohammed at school, but the SGD produced the words in English to help him discriminate between environments, while reinforcing his requests.

Conclusion

Multiple studies support the use of bilingualism, or instruction in both home and community languages, in different environments for children from ELL families (Reetzke, Zou, Sheng, & Katsos, 2015; Lund, Kohlmeier, & Durán, 2017; Hambly, & Fombonne, 2012). Language exposure for bilingual individuals appears to result in no further delays in speech; therefore families should be encouraged to expose their children to their native languages (Hambly, & Fombonne, 2012). However, there is a negative effect on the family if the bilingual child is only exposed to one language. For example, an educator might tell the mother of Nicholette, a child with ASD from Greece, to use English only at home. This might cause distress on parents, because they are not fluent and will forget when words should be used in different contexts. Additionally, it might cause further social isolation from family members if they are only introduced to the second language (Reetze, 2015).

Visual supports, such as activity schedules, task analysis, picture cues may help reduce some of the challenges faced with learners who are bilingual and have ASD. This is because children with ASD rely on visuals as their primary input (Banda, 2009). Visual supports and associated strategies are practical ways to supplement instructions for learners with ASD and help comprehend language effectively with low effort. The type of visual supports used are recommended after collaborating with stakeholders and will depend on the individual skills. Practitioners are suggested to take the time to understand the family’s goals and perspectives of the child’s disability, while being aware of cultural norms. Asking questions can help build rapport with families and establish a relationship that will help draw on the child’s strengths to support areas of weakness. Practitioners are encouraged to move from a, “melting pot”, mentality and not discourage families from maintaining bilingual environments or introducing a second language if needed for learners with ASD. Parents look for educational advice from practitioners and therefore should be wary of the language use recommendations they make to families. Results suggest that bilingualism in children with ASD do not experience additional language development (Hambly, 2012). Lastly, practitioners should evaluate individuals based on their needs and use family collaboration, culturally responsive instruction, and visual supports, as a part to successfully help learners meet academic, social, and behavioral goals.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM–5). Washington, DC: Author.

American Speech Language Hearing Association [ASHA]. (2014). Bilingual Service Delivery. Retrieved from https://www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Professional-Issues/Bilingual-Service-Delivery/.

Bailey, D. B., & Wolery, M. (1992). Teaching infants and preschoolers with disabilities. NJ: Prentice Hall.

Banda, D. R., Grimmett, E., & Hart, S. L. (2009). Activity schedules: Helping students with autism spectrum disorders in general education classrooms manage transition issues. Teaching Exceptional Children, 41(4), 16-21.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016, March 31). New Data on Autism: Five Important Facts to Know. Retrieved March 14, 2018, from https://www.cdc.gov/features/new-autism-data/index.html

Cohen, M. J., & Sloan, D. L. (2007). Visual supports for people with autism: A guide for parents and professionals (Topics in autism). MD: Woodbine House.

Dettmer, S., Simpson, R. L., Myles, B. S., & Ganz, J. B. (2000). The use of visual supports to facilitate transitions of students with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 15(3), 163-169.

Fahim, D., & Nedwick, K. (2014). Around the world: Supporting young children with ASD who are dual language learners. Young Exceptional Children, 17, 3-20.

Grantmakers for Education. 2013. Educating English Language Learners: Grantmaking Strategies for Closing America’s Other Achievement Gap. Retrieved from edfunders.org/sites/default/files/Educating%20English%20Language%20Learners_April%202013.pdf

Hambly, C., & Fombonne, E. (2012). The impact of bilingual environments on language development in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1342-1352.

Hodgdon, L. A. (1995). Visual strategies for improving communication: Practical supports for school and home. Troy, MI: Quirk Roberts Publishing.

Klingner, J., & Soltero-Gonzalez, L. (2009). Culturally and linguistically responsive literacy instruction for English language learners with learning disabilities. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 12(1), 4-20.

Lund, E. M., Kohlmeier, T. L., & Durán, L. K. (2017). Comparative language development in bilingual and monolingual children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Early Intervention, 39(2), 106-124.

Lubetsky, M. J., Handen, B. L., & McGonigle, J. J. (2011). Autism spectrum disorder. New York: Oxford University Press.

Matuszny, R. M., Banda, D. R., & Coleman, T. J. (2007). A progressive plan for building collaborative relationships with parents from diverse backgrounds. Teaching Exceptional Children, 39(4), 24-31.

Meadan, H., Ostrosky, M. M., Triplett, B., Michna, A., & Fettig, A. (2011). Using visual supports with young children with autism spectrum disorder. Teaching Exceptional Children, 43(6), 28-35

National Research Council. (2001). Educating children with autism. DC: National Academies Press.

Rao, S. M., & Gagie, B. (2006). Learning through seeing and doing: Visual supports for children with Autism. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 38(6), 26-33.

Reetzke, R., Zou, X., Sheng, L., & Katsos, N. (2015). Communicative development in bilingually exposed Chinese children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(3), 813-825.

Test, D. W., Spooner, F., Keul, P. K., & Grossi, T. (1990). Teaching adolescents with severe disabilities to use the public telephone. Behavior Modification, 14(2), 157-171.

Thompson, R. H., Cotnoir-Bichelman, N. M., McKerchar, P. M., Tate, T. L., & Dancho, K. A. (2007). Enhancing early communication through infant sign training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40, 15-23.

U.S. Department of Education. (2017). Digest of Education Statistics, 2017 (NCES 2006-05). Retrieved October, 20, 2017, from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=96

Vesely, C. K. (2013). Low-income African and Latina immigrant mothers’ selection of early childhood care and education (ECCE): Considering the complexity of cultural and structural influences. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(3), 470-486.

Wallis, K., & Pinto-Martin, J. (2008). The challenge of screening for autism spectrum disorder in a culturally diverse society. Acta Pediatrica, 97, 539- 540.

Yamanashi, J. (2016). Review of visual supports for visual thinkers: Practical ideas for students with autism spectrum disorders and other special educational needs. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 63(2), 267-269.

About the Author: My name is Valeria Yllades, I am a second year doctoral student at Texas A & M University in the Educational Psychology department. I received my undergraduate education at University of Texas Pan American and have a B.S in Psychology. I received my Master’s degree from Texas A & M University. I have worked at various clinics as a registered behavior technician implementing applied behavior analytic skills on individuals with autism spectrum disorders. My professional goals are to become a professor and conduct research at a Tier 1 University. My main areas of interest are communication interventions for CLD students with autism, and AAC interventions.

By Rebekah Caballero

Abstract

Culturize Every Student. Every Day. Whatever It Takes, by Jimmy Casas is an educational leadership that focuses on the building positive relationships with students, colleagues, administrators, district personnel, and in the community. Jimmy Casas uses his own personal experiences as an educator and administrator as well as Four Core Principals to shape his own belief system and encourage others to reform their own. By reforming their own belief systems, educators model for students and colleagues to help build a positive culture. This review analyzes the information provided in the book and discusses the skills and knowledge educators need to have to best serve their students and become leaders in the school and community. As educators begin to make changes in themselves and in the lives of their students, they will feel more confident and have less doubts about being effective. Building relationships, making a commitment, understanding the change process, and fostering positive traits in themselves and students will help to make a lasting effect on the school community.

Introduction

Culturize Every Student. Every Day. Whatever It Takes. by Jimmy Casas aims to get the reader to understand that they are in control of the change they want to make and can change their own lives as well as student lives. Jimmy Casas is currently the CEO of his own educational leadership company, J Casas and Associates, that is focused on providing high quality coaching support for teachers, principals, and school districts across the country. Through his own experience as a teacher and administrator, and his own school experience as a student, he tells the reader what made the difference for him as a student. As a young high school student, Casas was on the verge of not graduating when a teacher of his helped him to see the importance of working hard at school and showed him that he believed in him. In this book he presents Four Core Principals in creating a culture of change and reaching students. The Four Core Principals that help to make educators better are 1) Champion for Students, 2) Expect Excellence, 3) Carry the Banner, and 4) Be a Merchant of Hope. When teacher and principals act as leaders in the school, students believe in themselves and learn to be leaders of change.

Purpose and Thesis

Casas wants the reader to understand their role in the school society to better the lives of students. “Every Student, Every Day. Whatever It Takes” (Casas, 2017). Jimmy Casas sets a purpose to help educators be the change and get better as educators each day. Culturize Every Student. Every Day. Whatever It Takes. is about creating positive change in educators, students, communities, and schools. “Every child deserves the opportunity to be a part of something great” (Casas, 2017).

“Our goal should be to create schools and communities that equip young people in developing sills, habits, and competencies that produce an educated citizenry rooted in healthy, personalized, and productive relationships” (Casas, 2017).

The thesis in this book states hat using the Four Core Principals 1) Champion for Students, 2) Expect Excellence, 3) Carry the Banner, and 4) Be a Merchant of Hope, educational leaders (teachers, students, administrators, support staff, etc.) can begin the change process and create a positive, kind, honest, and compassionate school environment.

Just Talk to Me

Casas starts the book discussing the importance of talking with students and connecting with them on a deeper level. Students today are faced with many challenges whether it be at home, in school, through technology, etc. and having one person who believes in them can make a great difference. Casas uses his own childhood example of playing baseball as a child when he quit the team and the coach did not try to talk to him about his choice. The coach’s scoff in response is a memory that has stayed with Casas throughout his life. “… but it still serves as an important reminder to me in my work as a school leader to not underestimate how critical it is to take time to talk to students and understand what they see, feel, and experience” (Casas, 2017). He also asks readers to take a moment and analyze their own practices and if they are willing to be leaders of change. “Are we willing to do whatever it takes to culturize our schools to a level that defines excellence?” (Casas, 2017)

“Culturize: To cultivate a community of learners by behaving in a kind, caring, honest, and compassionate manner in order to challenge and inspire each member of the school community to become more than they ever thought possible” (Casas, 2017).

Culturize Every Student. Every Day. Whatever It Takes also puts into perspective who can help to lead a culture of change in schools today as they face many challenges. It is possible for students to become leaders and connect to their environment, but it is not a process that will naturally occur. Teachers, administrators, and staff must model for students how to be leaders, regardless of their official titles. Casas tells school teachers and leaders to be aware of their roles in culturizing schools. “We must take time to reflect on and be willing to be vigilant in examining our school cultures through the eyes of students and staff” (Casas, 2017). Schools face large challenges such as lack of funding/resources, teacher turnover/shortage, poverty, mental health issues, standardized testing, etc. While these challenges are large, Casas points out the patterns he sees from school which depict external factors, but teachers must also look at their own ability to lead effectively.

Casas stresses the importance of readers/teachers/school staff understanding their roles in the school. While not all these positions include administration, teachers and all staff in the school can lead by example and recognize themselves as leaders. In his own experience as a building principal, Casa describes how he wanted his staff to feel valued and appreciated. “I held myself accountable for the success and failures of my students and staff, always reflecting on what I could have done differently or more effectively to help them feel as though they were experiencing the success they desired” (Casas, 2017). Culturize Every Student. Every Day. Whatever It Takes discusses how great leaders inspire greatness. In a school environment, it can be easy for “average to become the standard”. There are countless challenges school face and it can difficult to build a culture of change, but leaders inspire others to improve the attitudes, believe in the abilities of students, team members, and push to be better than average.

Four Core Principals

Champion for Students

Educators who champion for their students are intentional about doing whatever it takes to help each of them reach their personal best. In schools, these educators already exist, but Casas wants readers to understand that they all have the potential to champion for students. In this chapter, Casas goes onto describe his own life changing champion, Mr. Morgan. In high school when Casa was in jeopardy of not graduating, Mr. Morgan helped him see how much a person believing in your ability can make a difference. “Fortunately for me, Mr. Morgan had taken the time to get to know me enough that he was able to see through my lack of confidence and recognize that somewhere inside was a kid with talent to do great things” (Casas, 2017).

Teachers and administrators like Mr. Morgan can help to ignite passion in students as well as in other teachers. When it can be so easy to be negative in school, champions choose to see the potential in each of their students and want to understand them and how they feel, think, and see the world. Champions are passionate teachers or administrators who hold the deep belief that connecting with kids and valuing their talents and voices is the first step to creating a kind school culture. Being a champion and helping to build a kind and positive school culture takes time and learning through experience. Not every choice or response from teachers, administrators, and school staff will be the best. Educators must be aware that their response is completely their choice and be able to put difficult situations in perspective and empathize with students.