Table of Contents

- Special Education Legal Alert. By Perry A. Zirkel

- Buzz from the Hub

- Evaluation of “The Effects of Screen Media Content on Young Children’s Executive Functioning”. By Samantha Beverly

- Establishing a Framework of Effective Communication with Families of Students from Diverse Cultures. By Alicyn Fifield

- Impact of Disability on the Families of Special Needs Students and Advocacy. By Carolina Fonseca

- Comparing: The End of Molasses Classes and Leading a Culture of Change. By Deborrah L. Griffin

- Bridging the Opportunity Gap in Special Education: Mastering the Florida Alternate Achievement Standards Through the Use of General Education Resources in a 3rd-5th Grade Self-Contained Classroom for Students with Mild to Severe Intellectual Disabilities. By Marissa Desiree Pardo

- The Significance and/or Effects of Parental Advocacy for Minorities and Students with Disabilities. By Loydeen Thomas

- Acknowledgements

Special Education Legal Alert

By Perry A. Zirkel

© July 2019

This month’s update concerns issues that were subject to recent federal appeals court decisions and are of general significance: (a) the application of Endrew F. and PRR, and (b) a surprising and puzzling wrinkle in tuition reimbursement jurisprudence. Both of these cases relate to other items available on my website perryzirkel.com.

|

In Albright v. Mountain Home School District (2019), the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals addressed various claims that a parent brought on behalf of her child with autism. Reflecting her highly contentious relationship with the district, the parent filed a series of due process hearings challenging the child’s IEPs. The first two complaints resulted in settlement agreements. Arising from the third hearing, which consisted of 11 sessions, the claims in this case included (a) a substantively inappropriate fourth-grade IEP, (b) the use of sensory integration techniques in the BIP, and (c) lack of meaningful parental participation. |

|

|

The hearing officer concluded that the IEP met the Rowley standard for substantive appropriateness. The parents contended that the IEP did not meet the Supreme Court’s revised standard in Endrew F. in light of her child’s “true” potential. The Eighth Circuit ruled that “however regrettable the disagreement between [the parent] and the remainder of the IEP team on this matter,” the child “made progress in a curriculum that was appropriate in light of her circumstances.” |

Further extending the two-year post Endrew F. case law analysis available on my website, this published Eighth Circuit ruling illustrates that Endrew F. has not had a significant outcomes effect in the courts. Rather than resolving the issue of the child’s potential as one of the presumably pertinent circumstances, the court merely repeated the Endrew F. dictum that the IEP need only be reasonable, not optimal. Similarly, the court responded to the parent’s four-year test score evidence by limiting its focus to the year in question, concluding that “although the test scores varied within the period, in total they demonstrate academic improvement.” |

|

The parent argued that the BIP’s sensory integration techniques were pseudoscientific in violation of the IDEA requirement for services “based on peer reviewed research [(PRR)] to the extent practicable.” The Eighth Circuit concluded that “alongside the ‘extensive’ use of peer-reviewed practices, the use of sensory integration techniques, which were recommended by [the child’s] occupational therapist, did not deny [the child] FAPE.” |

Again consistent with the general, although not uniform, trend of judicial case law for (a) the application of the IDEA to BIPs, including but not limited to their appropriateness, and (b) the interpretation of the IDEA’s qualified PRR requirement, this Eighth Circuit ruling was relatively relaxed and district-deferential in contrast with academic and professional norms. Note too that the court again did some deft ducking, avoiding directly addressing whether sensory integration techniques fulfilled the IDEA’s PRR provision. |

|

Faced with evidence of hundreds of pages of e-mails and transcripts of IEP meetings, the parent pegged her participation-violation claim on the district holding one of the meetings without her. However, the court concluded that (a) she chose not to attend the meeting despite the district’s erstwhile efforts and (b) even if it was a violation, it did not result in substantive harm to her child. |

The court’s ruling in response to this third claim is in line with the majority of the parent-participation cases. However, the court’s fallback, harmless-error approach missed the provision in the 2004 amendments of the IDEA requiring at the second step of procedural FAPE cases the alternative to substantive loss to the child—loss to the parents in terms of significantly impeding their right to participate in the IEP process. The outcome could have been different or the same, but failure to apply this alternate prong is clearly subject to question. |

|

The bottom line to this case, which is unfortunately typical of many cases that reach the judicial level, was “a profoundly toxic lack of trust” that had developed between the parent and the district. |

|

|

In Steven R.F. v. Harrison Central School District (2019), the Tenth Circuit addressed the appeal of a lower court decision that my December 2018 monthly legal alert summarized. Finding fatal procedural violations, including failure to comply with a complaint procedures corrective action order, the lower court reversed the hearing officer. The lower court concluded that the district had denied FAPE to the child with autism and ordering tuition reimbursement and attorneys’ fees. The school district appealed this lower court decision. In the meanwhile, the district provided the reimbursement pursuant to the IDEA’s stay-put provision. Surprisingly, the Tenth Circuit dismissed the appeal and vacated the lower court decision without addressing the merits of the case. |

|

|

The Tenth Circuit did not address the “merits,” which for tuition reimbursement cases typically includes whether the district had provided FAPE and, if not, whether the parents’ unilateral placement was appropriate. Instead, agreeing with the parents’ initial argument, the court concluded that the case was moot, because the district had already provided the relief that the parent sought in this case. |

Although mootness occasionally arises in other IDEA cases, this is the first published appellate case that has done so in a tuition reimbursement case. The court’s ruling poses major questions and concerns for this high-stakes remedy. First, although stay-put applies upon a hearing officer or, in two-tier state, a review officer reimbursement order, does it also arise, without such an agreement on behalf of the state, upon a judicial order? |

|

The school district counter-argued that the case fits the well-established exception to mootness, which is for cases that are capable of repetition and yet—due to the prolonged period for litigation—escape judicial review. In response, the Tenth Circuit agreed that this situation met the first required element for this exception—the challenged action expires prior to full litigation, because an IEP is for one-year and this appeal was well after the 2016-17 year. However, the Tenth Circuit concluded that the district did not meet the second prerequisite—a reasonable expectation that the complaining party would be subject to the same action again. Here, the court reasoned that even if the district had reasonable expectation that the parent would challenge the child’s most recent IEP, the procedural FAPE claims that the parent raised were specific to 2016–17 without proof that any future challenges would be the same. |

This part of the ruling is the second and stronger potentially limiting factor in the effect of the Tenth Circuit decision on other tuition reimbursement cases. The specific procedural violations in this case, as identified in my December 2018 legal alert, were quite unusual and specific to the year at issue. Would the Tenth Circuit reach the same conclusion about the mootness exception for a more typical FAPE challenge to a proposed IEP when in the course of litigation, the district proposed an IEP for the subsequent year that was similar to the originally challenged one and the parent promptly files or is reasonably expected to file for a second hearing? The answers to such questions are unclear for the Tenth Circuit, which encompasses the six states from Oklahoma to Utah. The effect of this ruling is subject to even less clear for jurisdictions outside the Tenth Circuit, which are not bound by its possibly narrow scope. The underlying concern is how to reach the merits upon appealing tuition reimbursement orders. |

|

Not so oddly, the parents also argued that the exception applied, but the Tenth Circuit disagreed for the same reason—lack of likelihood that the district would subject the parents to the same alleged procedural violations, with reasonable likelihood of parental challenge. |

The parent’s reason and the court’s rejection illustrate another concern. Although receiving the reimbursement (which they likely do not have to refund to the district), the parents lost not only the precedent in favor of their procedural claims but also their prevailing status to qualify for recovery of their attorneys’ fees. |

|

This case is a real head scratcher, raising various perplexing and practical questions for both districts and parents as to its legal effect. Stay tuned. |

|

Buzz from the Hub

All articles below can be accessed through the following links:

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-june2019-issue2/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-june2019-issue1/

https://www.parentcenterhub.org/buzz-may2019-issue2/

Tips for Parents: Summer Provides Time to Reinforce Positive Behaviors at Home

Emotional meltdowns can douse a family during summer break. Read this article from PAVE for tips to create a positive home environment that encourages expected behaviors.

14 Ways to Help Older Kids Build Motor Skills

Children develop gross and fine motor skills at different rates. And while there are many activities to help younger kids work on fine and gross motor skills, they’re not generally aimed at older kids who struggle with these skills. Here are 14 fun activities suited for older kids to help them build gross and fine motor skills without making it seem like more work. Also available in Spanish(14 formas de ayudar a chicos más grandes a desarrollar habilidades motoras).

Summer Reading with Bookshare

Bookshare’s Summer Reading Lists provide enriching level-appropriate tales of fantasy, science fiction, #ownvoices, STEM, and other interesting topics. Combined with Bookshare’s helpful audio, word-level highlighting, braille, and customizable text and color features, summer reading could not be easier. Explore fantastic titles handpicked for young readers, middle school students, teens, and adults.

Why We Should Let Our Kids Be Bored

When her child complains, “I’m bored,” this mom no longer suggests activities to cure the ennui. Here, she explains why those moments should be treasured. “That’s great you’re bored. That’s when people have the best ideas!”

Intervening to Prevent a Dropout | Video

Research has shown that middle school is the key moment when, absent effective intervention, students can fall into the patterns that lead them to drop out during high school. Identifying the risk factors associated with students who drop out of high school is featured in this 6-minute video excerpt from FRONTLINE: “Middle School Moment.”

Young Children Exposed Prenatally to Substances

This new ECTA web page provides key research, policy, state guidance and examples, and evidence-based practices for supporting families and young children exposed prenatally to substances.

Federal Data and Resources on Restraint and Seclusion

This 12-page report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) discusses (a) how the Department of Education collects data on the use of restraint and seclusion, (b) what the Department’s data tell us about the use of restraint and seclusion in public schools, and (c) resources and initiatives at the federal level to address the use of restraint and seclusion. A 1-page Highlights is also available, as is an accessible PDF version.

Students Most at Risk of Getting Spanked at School Are Black or Disabled, Data Show

Nineteen states, the vast majority in the South, permit school personnel to strike students with belts, rulers, homemade wooden paddles, or bare hands in the name of discipline. Whether a student is actually at risk of physical punishment often depends on race, geography or disability status, according to a new analysis of 2013-14 federal education data by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Improving Federal Programs that Serve Tribes and Their Members: High Risk Issue

Concerns about ineffective federal administration of Indian education and health care programs and federal mismanagement of energy resources held in trust for tribes and their members have resulted in the designation of federal management of these programs as “high risk.” The link above takes you to the GAO report on this issue. There’s also a 2-minute video summary available, High Risk: Programs That Serve Tribes and Their Members.

A Year in the Life 2018: Parent Centers in Action | Here’s the infographic CPIR produced after the data were in and crunched. It’s 2 pages (designed to be printed front/back to become a 1-page handout or mini-poster), in PDF format (1 MB), in full color. It’s a stunning portrait of what can be achieved by a few, extremely dedicated people for the benefit of so many.

Adaptable Infographic for Parent Centers to Use | This infographic is designed so it can be easily changed, inserting your Center’s numbers and data results into key blocks of information. It’s provided as a PowerPoint file and results in an infographic that’s 1-page long. Easy to insert your Center-specific accomplishments, and add your logo and contact information.

Quick Guide to Adapting the Infographic | Also download this 2-page guide that will show you, with screenshots, where your Center-specific information needs to be inserted. We provide this guide just in case having such a “checklist” would be helpful.

Reinforcing Your Child’s IEP Goals Over the Summer

If your child has an IEP, it may or may not cover summer. Some kids get extended school year services built into their IEPs, but many don’t. If your child isn’t attending a summer learning program, you may worry about how she’ll keep up while school’s out. But you can help reinforce her goals, even if she doesn’t have school services in the summer. This article offers how-to’s. And it’s available in Spanish, too (Reforzar los objetivos del IEP de su hijo durante el verano).

Living with Spina Bifida: Series

Here’s an article series from eparent.com on living with spina bifida, with separate articles on infants | toddlers and preschoolers | school-aged children | and young adults.

Evaluation of “The Effects of Screen Media Content on Young Children’s Executive Functioning”

By Samantha Beverly

Abstract

In this paper, the research article “The effects of screen media content on young children’s executive functioning” will be analyzed. The author’s research problem, measurement of the experiment, research design, sampling, data collection, data analysis and results will be discussed throughout this article analysis.

Keywords: executive functioning, screen media, educational applications, educational television, cartoons

Research Problem

Executive functioning is the higher order thinking processes that are responsible for negotiating goal directed behavior within the cognitive mind. The goal directed behaviors that are included in executive functioning are self-regulation, working memory, inhibition, and attention. Huber (2018) conducted this experiment to determine how executive functioning in young children is immediately affected by screen media of different types (Huber, 2018). Huber conducted extensive research on existing research experiments that have been done on the effects of screen media on young children. In the past, the research has mostly been based on the use of television and the effects that it has on the brain, however being in the electronic age that we live in, Huber decided to research specifically how touchscreen affects executive functioning verses the effects of television on young children. She was specifically interested on the effect of media exposure on the executive functioning on children younger than four years old as there is little research done in this specific area. Huber was also very interested in looking specifically at working memory and response inhibition being effected by screen media due to the instant gratification that screen media provides for us today. Huber was interested in examining the way that delayed gratification was affected by an app and by a cartoon. She began this project wanting to explore the possibility of the new age of apps affecting young children’s delayed gratification more than watching cartoons. Prior research indicates that exposure to educational or child/directed programs had no effect on executive functioning at either 12 months or 4 years of age.

Huber and the other researchers determined that identifying the factors that affect the executive functioning in the performance of children is important. The researchers identified two executive functioning areas, hot and cool. Hot executive functioning is activated during emotive or heightened social situations. The researchers measured this by tasks with intrinsic reward such as delay of gratification. Cool executive functioning is during emotional neutral cognitive skills. The researchers assessed this by abstract tasks that were related to children’s social and emotional readiness. Both the hot and cool executive functioning skill sets are essential to children’s daily functioning and are directly related to children’s academic success now and in the future.

Measurement

Participants’ baseline scores were recorded through a series of task analysis tests, then the screen intervention materials were administered to each participating child. After the baseline for executive functioning was established the children’s behavior was coded through a trained coder who looked at video of the participating children. For reliability purposes, the researchers set it up so that a random subset of cases were coded by an additional observer who was unaware of the conditions of the experiment so that biases could be avoided. Huber reported that the coder’s reliability was assessed with Krippendorff’s alpha (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007). Coder’s reliability was assessed for the Spin the Pots task as well as the Reverse Categorization task.

Each task’s goal was to accurately measure different sections of executive functioning. The Spin the Pots task that measured working memory was measured by the total number of possible trials, which was 16, minus the number of errors the participating child made through the task. In the Reverse Categorization task that measured task switching and response inhibition, the total number of correctly sorted objects in the reverse categorization trial calculated the children’s actions. For Gift Delay task, the participants’ scores were measured on whether the bag was touched or not. If the bag was touched, the child did not receive a successful delay of gratification score.

Huber and the other researchers who worked on this research paper conducted three different screen conditions through an iPad 2. In the first condition named, EduApp, a child plays with an app that is designed to assist children in learning shapes and complete a puzzle. The second screen condition was the cartoon condition. Children watched part of an episode of a popular child’s cartoon program, and the final condition was called EduTV where the children watched an episode of an educational children’s program. For this stage two coders were assigned to assess the videos in the EduTV and the cartoon conditions. The coders were measuring the pace of each program by looking at the complete scene changes per minute within the shows and the fantastical events per minute. The researchers defined fantastical events as events that defied the laws of physics. The coders determined that the cartoon program displayed 2.99 fantastical events per minute and the EduTV program had a rate of 1.40 per minute. As for the pace of the two television programs, the cartoon program displayed 3.18 scene changes per minute and this surpassed the EduTV program by 2.30 changes per minute. Based on assessing the EduApp condition, it was not possible for the researchers to assess the app in the same way. However, based on the narrative of the app, there was 1 fantastical event per minute and about two and a half scene changes per minute. Based on this analysis, the researchers did not find EduApp to be classified as fantastical.

Research Design

For this study, executive functioning was measured through multiple tasks. Some tasks targeted working memory, a major function within executive functioning, another targeted task switching and response inhibition, while others specifically targeted delay of gratification. Executive functioning was also measured through screen intervention materials. “Spin the pots” was one of the tasks that measured visuospatial working memory in the participating students. The Spin the Pots task is identified as a “cool” executive functioning task where students helped the experimenter hide stickers in six of eight small boxes where two of the boxes remained empty were placed on a Lazy Susan. The experimenter covered all the boxes with a towel and rotated the lazy Susan all the way around. The experimenter then lifted the towel and asked children which box they wanted to open. This task’s goal was for the participant to find all six stickers one at a time with as many errors as possible. This was assessing the children’s working memory before exposure to the screen media. The participating students were given a maximum of 16 trials to find all of the stickers within the boxes. The scores were recorded and then calculated as the total number of possible trials, meaning 16 minus the number of errors each child made.

The second trial that was used to evaluate students executive functioning was called “Reverse Categorization”. Reverse categorization measured the children’s ability to task switch and their response to inhibition, and this task also fell into the cool executive functioning category. In this task, children were asked to first sort 6 objects into the corresponding bins that were based on size. After sorting all the big objects into the big bin and the small objects into the small bin, the examiners reversed the rules and asked the children to sort 12 objects incongruently. The researchers state that the two-year-old children were able to complete the task using large and small blocks, and the three-year-old children were able to sort “mommy” and “baby” animals that the children would have found typical into buckets that were labeled with an image of a human mother on one bin and a human baby on another. In the forethought of internal validity and addressing student misconceptions, the researchers established that the participating children could in fact differentiate between big and little objects previous to implementing this task. The children’s scores were calculated as the total number of items that were correctly sorted in the incongruent trials, which was 12. The objective of this task was to test if the children had the ability to properly switch from one task (sorting objects into alike bins) to another task (sorting objects into opposite bins).

Gift Delay was a task designed to measure the participating children’s tolerance for delayed gratification. In this task, a gift box was given to the children who were seated at a table, but the examiner had “forgotten” to get the bow for the preset. The children were asked to wait in their chairs until the examiner got the bow and the children were not to touch the box until the examiner returned. The examiner waited a total of three minutes to return to the children. The children’s performance was scored based on if the bag was touched. If a student did not touch the gift box, then the students were labeled has having a successful delay of gratification. A total of 13 participants were removed from the Gift Delay analysis due to experimenter error as reported by the researchers.

The screen intervention materials were introduced to the participating children through three different condition areas. EduApp was an app that the children manipulated through the use of an iPad 2. EduApp was classified as non-fantastical by the researchers that administered this study, through EduApp the children used a specific app called Shiny Party. Shiny Party is an app that presents young children with the opportunity to learn to complete puzzles and shapes through a narrative that was interesting to the participating children. The content of this app is deemed educational by the developers of Shiny Party on the app store, and also is physically interactive as it is to be played on a touch screen. This app is appropriate for the age of the participants.

The next screen intervention material was the cartoon condition and the EduTV condition. For the cartoon condition, examiners had the participating children watch a part of an episode of the cartoon Penguins of Madagascar. The Penguins of Madagascar is a cartoon program meant for enjoyment and is not educational as determined by the researchers and advertisements. In the EduTv condition, children watched a portion of Sesame Street where self-regulation was being taught during that particular episode. In the episode, Cookie Monster was faced with achieving a clear goal where he had to “stop and think” and use problem solving skills. Due to the content within this television program, EduTV condition was determined to be of high quality standards due to the fact that there was a learning goal that was clearly stated to the viewers.

Sampling

The researchers had a total of 96 children age 24-48 months participating in the study. 54 of the children participating in the study were boys, and 42 were girls. Of this sample, the researchers reported that 9 children were excluded from the study due to their unwillingness to complete all of the executive functioning tasks in the study. Previous touchscreen usage was quantified by whether parents indicated that their children had ever used a touchscreen to watch videos or play games. Previous touchscreen usage was found to be common among participants at 93 percent. The sample group was composed of participants who came from middle- to upper middle-class homes where the median range of annual household income was reported $1000,000 – $150,000 (AUD) as reported by Huber (2018). The families were recruited from the surrounding suburbs in Swinburne University of Technology’s greater metropolitan area in Australia. This research was targeting young children who would have access to touchscreen devices; therefore this sample population is accurate to the overall population.

Data Collection

Throughout this research paper data was collected in multiple areas to establish a baseline and then again to determine an effect size of the screen interventions that were put into place. Throughout the three screen interventions trained coders were recording the children’s behavior during the tasks. As mentioned previously within this article analysis, for assurance of reliability of the coders, additional observers who had no biases due to ignorance of the experimental conclusions were brought in to assess randomized trials. The research article expressed that there was a robust agreement on the ordinal scores for each task that the participants completed.

A statistical analysis using binary logistic regression in order to study the effects of the three different screen activity interventions and the effects that it had on the participants delay of gratification was compared to the likelihood of the child not touching the gift in the Gift Delay task. The cool executive functioning scores were calculated by subtracting the baseline data from the post-screen activity scores. This data for both the pre and post-screen activity tasks were charted on a bar graph to show the significance between the pre and post task scores, if a change was recorded. Baseline performance on the executive functioning tasks was included in the analysis of each task as a control as there was a potential for ceiling effects in a subset of the participants from the group.

Results

The preliminary analysis of the data revealed no significant effect from gender of the participant or previous exposure to screen media. Due to this analysis, Huber did not consider these factors in the official results within the study. As mentioned previously, executive functioning in this study was split into two categories; hot and cool, to assess separate executive functioning categories.

The results for hot executive functioning skills indicate that out of the participating children who passed the Gift Delay task, scored 84 percent for EduApp, 63 percent for EduTV, and 61 percent for cartoons. These percentages were calculated by a binary logistic regression to compare the effect of the screen conditions on children’s Gift Delay task performance. The results of the screen based interventions show that the participating children’s executive functioning in delay of gratification was more likely after playing the educational app than after the children watched the cartoon. After watching the educational TV program, the children showed no significant change in their delay of gratification. This data indicated that parents and guardians should consider educational apps differently than cartoons in respect to the effects on young children’s executive functioning. Research still shows that the longest delay of gratification was found to be after extended physical activity as per Lillard and Peterson (2011).

The results for cool executive functioning showed that the baseline for executive functioning showed that children within EduApp, EduTV and Cartoon groups would not differ significantly, and these same participants did not show any significant difference in the Spin the Pots performance and Reverse Categorization as the dependent variable. This research article reports that, under certain circumstances, children’s cool working memory part of their executive functioning is also affected through the viewing of screen media. Overall, there was no significant evidence of cool executive functioning being influenced by the three screen media interventions conducted through this research.

The key finding in this study was that compared to watching a cartoon, using an educational app on the iPad had beneficial effects on children’s hot and cool executive functioning performance. The researchers found this finding to be consistent in two of the three measures of executive functioning skills that were assessed. The most impressive, over all three executive functioning tasks, the shiny Party educational app never showed an unfavorable affect on the participating children’s executive functioning. The screen interventions had a significant effect on the participating children’s delay of gratification and performance within working memory. When the educational TV program was excluded, the researchers had a better understanding of what features of the screen-based media interventions were effecting the executive functioning the most and what specific tasks within executive functioning were targeted significantly.

Conclusion / Reviewer’s Contribution

If the reviewer of this article were to conduct this study again, she might consider adding an additional screen media intervention. The screen-media that the reviewer might consider adding to the study would possibly be the effect of playing non-educational games on the iPad on young children’s executive functioning. The reviewer has taken interest in this topic of executive functioning and its connection to screen-media due to the fact that the reviewer has observed many young children become pacified through smart devices and receive instant gratification through an enjoyable activity. The research conducted in this study was found to be very detailed and points where validity of the experiments might have been threatened were addressed and dealt with appropriately in this study. Due to the attention to detail in which this research was conducted, the reviewer would keep all of the data presented in this research article. The only portion of the research article that the reviewer might change would possibly be the Gift Delay task because 13 participants were removed from the analysis due to an experimenter error. The reviewer found that the results from the Gift Delay task were the most important baseline scores as a majority of the screen-media interventions were compared to delay of gratification. The reviewer might delete the reverse categorization due to the fact that task switching was not assessed as heavily as the other executive functioning skills.

References

Lillard, A.S, & Peterson J. (2011). The immediate impact of different types of televisión on young children’s executive function. Pediatrics, 128, 644-649

Huber, Brittany, M.Y. (2018). Evaluation of “The effects of screen media content on Young children’s executive functioning”. Journal

Establishing a Framework of Effective Communication with Families of Students from Diverse Cultures

By Alicyn Fifield

The United States is known to be one of the most culturally diverse countries in the world. Although this can add richness and strength to the country, it also can lead to errors in judgement because of a misunderstanding of cultural perspectives and norms. In education an error in judgement can cause a student to suffer academically and ultimately not reach his/her potential. This is an error that can be avoided when schools and families become educational partners and engage in effective communication practices for the benefit of the students being educated. It needs to be the goal of all educators to establish a community wherein they can engage in effective communication practices with families of all cultural backgrounds.

Developing a philosophy that demonstrates respect for cultural differences and regards a student’s culture as an asset to their education is the first step to developing a multicultural framework that maintains high expectations for every child (Gallegos, 2017). It is imperative that educators start early in establishing an atmosphere of trust between home and school. In order to have positive outcomes for students, schools must reach out to families of diverse cultures and build culturally responsive collaborative partnerships (Rosetti, Sauer, Bui, & Ou, 2017). Since it is not possible to be family-oriented without being culturally responsive, educators must work to develop both their cultural competence and cultural responsiveness (Povenmire-Kirk, Bethune, Alverson, & Kahn, 2015).

Early Intervention

Early intervention and communication with families is critical. New Mexico School of the Deaf, NMSD, employs early intervention specialists that live within the community. This leads to frequent interaction within the community (Gallegos, 2017). Interaction between diverse cultures reduces prejudice and leads to more empathy (Perrigrew, Tropp, Wagner, & Christ, 2011). The community in which the school is based has a high population of Native American and Hispanic heritages. NMSD strives to hire early development specialists and deaf mentors that are not only fluent in American Sign Language, but also Native American and Spanish. They also provide opportunities for their employees to interact with their students and their families. NMSD provide academics in a culturally responsive educational framework (Gallegos, 2017).

Building a Collaborative Partnership

The special education system can be daunting for any parent but parents from culturally diverse backgrounds experience even more difficulty. They often attend more IEP meetings but have less opportunity to provide any meaningful input into their child’s education. Often assessment results are not translated into the family’s native language and there is a lack of skilled interpreters present (Rosetti, Sauer, Bui, & Ou, 2017). Educators should not discourage use of the family’s native language. Medina and Salamon found that using both home and school languages with children diagnosed with ASD led to growth in both expressive and receptive language skills (2012). Teachers can utilize “cultural brokers” to bridge the gap between home and school and foster better home school relationships. Cultural brokers are people who are bicultural with the culture of the student’s family. These could be other staff members already present at the school or parent liaisons. It will be imperative to build trusting relationships with parents by involving them and other important community members in school activities (Povenmire-Kirk, Bethune, Alverson, & Kahn, 2015).

Creating a Multicultural Classroom

Teachers must begin by first examining their own cultural biases and perceptions (Taylor, Kumi-Yeboah, & Rinlasben, 2016). Educators can have cultural biases toward students who are different than the typical student they are used to teaching (Abou-Rjaily & Stoddard, 2017). They can develop their cultural awareness by attending diversity trainings and community events where they can interact with diverse cultural groups (Povenmire-Kirk, Bethune, Alverson, & Kahn, 2015). Teacher can incorporate cultural experiences into educational experiences while maintaining strong academic content. In a study by Sosin, Bekkala, and Pepper-Sanello, students were asked as part of an art project to learn about the effects of culture from various cultures and time periods. The students assessed at the end of the semester had some of the highest gains in creative and mental growth (2017). Effective teaching is a process that looks at every aspect of instruction when choosing the subject matter, lessons planning, and different methods and strategies Ajongakoh Bella, (2016). It is also essential that the teacher foster a classroom atmosphere of tolerance and respect for all students and their cultures. Demonstrating an attitude that is positive and non-judgmental to all students will lead to students feeling accepted and safe (Kulikova, Shalaginaova, & Cherkasova, (2017).

Effective Communication: The Key to Student Success

It is important to develop practices early on that will lead to working collaboratively with families from culturally diverse backgrounds in order to ensure that their students receive a high quality educational experience. Establishing as atmosphere of trust is essential in order to build this partnership (Rosetti, Story Sauer, Bui, & Ou, 2017). Teachers must be willing to examine their own cultural backgrounds and biases in order to actively learn and develop a more culturally responsive framework to base their relationships with their students and their families.

References

Abou-Rjaily, K. & Stoddard, S. (2017). Response to Intervention (RTI) for Students Presenting with Behavioral Difficulties: Culturally Responsive Guiding Questions. International Journal ofMulticultural Education, 19(3), 85-102.

Ajongakoh Bella, R. (2016). Investigating Psychological Parameters of Effective Teaching in a Diverse Classroom Situation: The Case of the Higher Teachers’ Training College Maroua, Cameroon. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(23), 72-80.

Gallegos, R. (2017). Early Contact, Language Access, and Honoring Every Culture: A Framework for Student Success. Odyssey, 12-16.

Kulikova, T.,Shalaginova, K.S., & Cherkasova, S.A. (2017). The Polyethnic Competence of Class Teacher as a Resource for Ensuring the Psychological Security of Pupils in a Polycultural Educational Environment. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 6(3), 557-564. Doi: 10.13187/ejced.2017.3.557.

Medina, A.M., & Salamon (2012). Current Issues in Teaching Bilingual Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAASEP, 69-75.

Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L.R., Wagner,U. & Christ, O. (2011). Recent Advances in Intergroup Contact Theory. International Journal Intercultural Relations, 35(3), 271-280. Doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001.

Povenmire-Kirk, T.C., Bethune, L.K., Alverson, C.Y., & Gutmann Kahn,L. (2015). A Journey, Not a Destination Developing Cultural Competence in Secondary Transition. TEACHING Exceptional Children. 319-328.

Rossetti,Z., Story Sauer, J., Bui, O., & Ou,S.(2017). Developing Collaborative Partnerships with Culturally Linguistically Diverse Families During the IEP Process, TEACHING Exceptional Children. 49(5). Doi: 10.1177.0040059916680103.

Sosin, A.A.,Bekkala, E.,Pepper-Sanelo,M. (2010). Visual Arts as a Lever for Social Justice Education: Labor Studies in the High School Art Curriculum, Journal for Learning Through the Arts 6(1). 1-23.

Taylor, R., Kumi-Yeboah, A., Ringlanben,R.P. (2016). Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions towards Multicultural Education & Teaching of Culturally & Linguistically Diverse Learners, Multicultural Education, 42-48.

Impact of Disability on the Families of Special Needs Students and Advocacy

By Carolina Fonseca

Abstract

Having a child can be one the greatest joys parents and families share throughout their lives. However, for some families, the joy quickly turns into fear, anxiety and confusion when they are told their child was diagnosed with a disability. Many emotions come into play when raising a child with special needs and this can impact families in many ways, including their involvement in their education and advocating for services. The research studied focused on the effects special needs children have on their families, the roles families play in advocating for their family members, the services provided to special needs children and the transitioning process. It is evident that students with special needs have a deep impact on their families and the roles they play as primary advocates and caretakers. However, there is conflicting data on whether families consider the impact to be negative or burdensome. Research conducted also seems to be limited to school age children and not on those transitioning into adulthood with aging parents. This warrants for further research on the impact that disability has on families of special needs students and parental advocacy, specifically those with aging parents.

Caring for a child with special needs can be a difficult task to undertake as no parent is ever prepared for the unique needs children with disabilities face. Many of the same issues parents of a typical child has to face, are also experienced by parents of special needs children, however, they may be more frequent and more intense. Caring for a child with special needs often requires specialized knowledge and collaboration with healthcare professionals, both of which fall out of the norm for typical caregiving (Leiter et al., 2004). Some areas that can warrant extra care and attention include areas such as personal care and hygiene, medical care, management of behaviors and financial and social needs (Kishore, 2011). In addition to the emotional aspect of caring for a child with a disability, parents must also undertake the role as primary advocates for their child. The support and guidance of caretakers and parents are long-term and necessary throughout the life of the individual with a disability. As individuals with disabilities age, so too do their parents, which changes the dynamics of the family and the way they advocate as roles change and responsibilities are shifted (Grossman & Magaña, 2016).

Effects on Family and Caregivers

Families of individuals with special needs are greatly affected by the care they must provide for their family members. This involves emotional support, financial support, and often times medical support. In a study by (Vohra et al., 2013), it was found that marital stability was negatively impacted in families with special needs individuals in comparison to those without. It was also noted that financial burden was higher specifically in parents of children with ASD versus parents of children with other developmental disabilities. Similarly, family members of individuals with ASD also reported they had more difficulty accessing services and quality care than those with other developmental disabilities. According to (Leiter et al., 2004), employment is also affected by having a child with a disability as many caretakers reduce their workload or completely leave the workforce to care and advocate for their children. As the children with special needs go through adolescence and transition into adulthood, the roles of their parents as primary caretakers and advocates often shift on to siblings who must now care for their aging parents as well as their family member with special needs. It is important to note that not all families are impacted in the same manner.

Advocating

The roles of family members in regard to education has changed as well, as it now focuses and emphasizes on their decision-making and empowerment in advocating for their family members. Advocating for a child or adult with special needs has now become the primary focus of many caretakers. According to (Starr et al., 2010), it was found that many families of children with special needs are reporting that they feel schools and teachers are lacking training and knowledge when it comes to specific disabilities such as ASD. More students are being homeschooled due to perceptions that schools are not meeting their needs or negative experiences that they have had with schools. In another study however, after conducting research and gathering data through questionnaires, it was found that many families generally had positive perceptions about schoolteachers and described them as “caring” and “supportive” (Siddiqua & Janus, 2017). The conflicting results in these studies further strengthens my belief that more research should be conducted in this area. It was noted by (Hess et al., 2006), that family input and support are crucial in effectively meeting the needs of special needs learners.

Difficulties with Advocacy

Many families become overwhelmed with resources and struggle to advocate for their children, often turning to educators for advice. The primary context in which educators are used in the advocacy process is through the Individualized Education Program (IEP) process (Burke et al., 2016). During this time, they meet with families to coordinate services to best meet the needs of the family members. It was noted by the author, that during these meetings families often keep their comments and speaking to a minimum while allowing the teacher to make all the calls. This causes a lack of communication and does not allow for parents to become familiar with key terms or to fully understand the purpose of the IEP. In this particular study, it was found that these five components were necessary to overcome the barriers in advocacy: develop rapport, establish clear expectations, learn about the child and family, educate and empower, and participate in IEP meetings. (Burke et al., 2016)

Planning for the Future and Transitioning

As children with disabilities go through different stages of life and transition from adolescence to adulthood, their families also play a big role in planning for the future and the transition process. The overall goal of family members of special needs children is to assist them in living meaningful lives and ensuring they go on to live as independently as possible. In a study by (Betz et al., 2015), the focus was on the transition for adolescents and emerging adults with special needs in regard to health care. Based on this study, some common themes were found when discussing the transition process with families of individuals with disabilities. They included changing expectations in parental planning, changing expectations pertaining to future planning, changes in the parental role, changes in the children’s roles, exploration of parental perspectives of the transition experience, parent stressors, perspectives about helpful support and services, and parent’s perceptions of the child’s experience. (Betz et al., 2015). In regard to transitioning out of the school system, in an article by (Cavendish et al., 2016), it was recommended that students and families are present during IEP development and transition planning. This promotes quality collaborations between school teams, families and students. Three phases were recommended to ensure the best possible outcome in the transition process: Pre-IEP, IEP and Post-IEP meetings. During Pre-IEP teachers build rapport and trusting relationships with families and allow students so self-advocate by being present in meetings and becoming familiar with the IEP process. During the actual IEP meeting, students are encouraged to speak up, advocate for themselves and to be able to self-evaluate. It also allows for parents to have input and to collaborate on goal and objective writing. Post-IEP meetings allow for students to provide feedback, for parents to follow up and for future vocational programs or transition centers to be aware of all the items and goals set in place on the IEP.

Conclusion

Based on the articles reviewed, it is evident that families are deeply impacted by disabilities of their family members with special needs. It affects several areas of their lives and becomes a life-long endeavor. The literature suggests that families are an extremely important part of the advocacy process and care of those with special needs. There was conflicting data on whether families would consider themselves negatively affected by their family member’s disability. I believe there should be more research done on the aging population of special needs individuals and the care they receive when family members are no longer present or involved in their advocacy and/or caretaking. This research should focus on the care, advocacy and transitioning process of adults with special needs

References

Betz, C. L., Nehring, W. M., & Lobo, M. L. (2015). Transition Needs of Parents of Adolescents and Emerging Adults with Special Health Care Needs and Disabilities. Journal of Family Nursing, 21(3), 362-412. doi:10.1177/1074840715595024

Burke, M. M., & Goldman, S. E. (2016). Documenting the Experiences of Special Education Advocates. The Journal of Special Education,51(1), 3-13. doi:10.1177/0022466916643714

Cavendish, W., Connor, D. J., & Rediker, E. (2016). Engaging Students and Parents in Transition-Focused Individualized Education Programs. Intervention in School and Clinic, 52(4), 228-235. doi:10.1177/1053451216659469

Grossman, B. R., & Magaña, S. (2016). Introduction to the special issue: Family Support of Persons with Disabilities Across the Life Course. Journal of Family Social Work, 19(4), 237-251. doi:10.1080/10522158.2016.1234272

Hess, R. S., Molina, A. M., & Kozleski, E. B. (2006). Until somebody hears me: Parent voice and advocacy in special educational decision making. British Journal of Special Education, 33(3), 148-157. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8578.2006.00430.x

Kishore, M. T. (2011). Disability impact and coping in mothers of children with intellectual disabilities and multiple disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 15(4), 241-251. doi:10.1177/1744629511431659

Leiter, V., Krauss, M. W., Anderson, B., & Wells, N. (2004). The Consequences of Caring. Journal of Family Issues, 25(3), 379-403. doi:10.1177/0192513×03257415

Starr, E. M., & Foy, J. B. (2010). In Parents’ Voices. Remedial and Special Education, 33(4), 207-216. doi:10.1177/0741932510383161

Vohra, R., Madhavan, S., Sambamoorthi, U., & Peter, C. S. (2013). Access to services, quality of care, and family impact for children with autism, other developmental disabilities, and other mental health conditions. Autism, 18(7), 815-826. doi:10.1177/1362361313512902

Comparing: The End of Molasses Classes and Leading a Culture of Change

By Deborrah L. Griffin

Abstract

With the passage of P.L. 94-142, also known as The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA), in November 1975, parents of children with disabilities were granted specific rights in regard to their children’s education (Valle, 2011). The passage of IDEIA, should have improved the education needs of children with disabilities and ensured that parents have an active voice in their child’s education. Unfortunately, parents today feel as though they are not able to fully advocate for their children and their educational rights. As educators, it is important to ensure that we are doing the best for the students and families we teach and come into contact with.

Comparing: The End of Molasses Classes and Leading a Culture of Change

Parents always want the best for their children, especially when it comes to their academic careers. Parents who have children with disabilities are not any different. In fact, there are federal laws that ensure they are active members in their child’s academic career (Valle, 2011). Parents were legally given rights to advocate for their children and the educational choices almost 45 years ago, yet very few parents are able to understand what those rights are or have the courage to truly advocate for their children against the school systems (Brown, et al., 2011). Parents, especially those who have children with autism, feel that their educational needs are not being met or taken seriously (Starr & Foy, 2012). It is imperative that school systems, teachers and parents are able to work together and create the best future for children with disabilities.

Parents Negative Issues with School Systems

Though researchers are just beginning to examine how parents’ rights and the educational needs for the children are being met (Brown, et al., 2011), it is obvious that it is a topic that requires greater insight. According to Starr and Foy (2012), a major factor that cause parents to have negative feelings towards their children’s’ education is the lack of knowledge teachers and staff members have with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and being able to utilize the proper interventions. When teachers and staff members are not trained properly to teach students with autism, it can create a negative learning environment for the student, which can ultimately lead the parents to homeschool their children to prevent future negative interactions through the educational setting (Starr & Foy, 2012). Students who have autism often times have a wide variety of needs that require support inside and out of the school system. This can be said for student who have high functioning, moderate functioning, or even low functioning autism, and unfortunately, parents at each functioning level feel as though certain needs are not being met (Brown, et al., 2011).

Teachers and staff need to have the understanding that students with autism need direction instruction with social skills and often times thrive and require structure to prevent negative behaviors (Starr & Foy, 2012). It is unfortunate that when parents try to fight for their children’s educational rights, that they are seen as difficult parents and are given a negative reputation when they are just trying to do the best for their child (Starr & Foy, 2012). When effective collaboration and communication exist between homes and schools, the educational teams are able to make decisions that are putting the needs of the students ahead of any other external forces or agendas.

Advocacy

Prior to IDEIA, public schools did not have to provide services to students with disabilities. Since then, students with disabilities are guaranteed to have free, appropriate, public education (FAPE) provided to them (Burke, 2013). Part of FAPE also allows students who have a disability to have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) which contains the any related services, classroom testing and instruction accommodations and modifications, as well as state testing accommodations and modifications. Parents must be provided with notices to attend each IEP and have procedural safeguards to ensure their children’s IEPs are being followed and their rights are not being infringed upon. The biggest struggle comes when parents do not understand their rights or are too afraid to act on their rights. A recent study concluded that 70% of parents who have children with disabilities feel that services are lost or not being given to their children properly because they do not fully understand their rights (Burke, 2013). The National Council on Disabilities documented that more than 400 parents have attended IEP meetings where IEPs were pre-prepared making them feel left out of the process and often confused due to the amount of technical and educational terms used during the meetings (Valle, 2011). Far too often, the input of parents are pushed to the side and not actually taken into account when discussing the educational future for students with disabilities (Burke, 2013) (Valle, 2011), since they are just parents and do not have the expert input for creating and implementing IEPs. When this happens, the relationship between home and school is destroyed and can increase the stress level for the parents (Burke, 2013).

One way to help parents ensure that their voice is being heard and that their educational rights are not being infringed upon is to hire advocates who are trained to navigate the relationship between parents, school systems, and the special education process. Advocates have knowledge of special education laws and are able to work as an unbiased middle man, so to speak, that is wanting what is truly the best option when it comes to education and educational services for students with disabilities. Advocates have the ability to improve collaboration between parents and schools (Starr & Foy, 2012). Unfortunately, there are very few training programs for advocates, which can hinder the access parents may have to advocates. There is also not a clear cut best way to train advocates, since there are not enough studies conducted to determine the efficacy of the different training programs (Burke, 2013).

Parent-School Collaboration

When parents, teachers, and other school staff members are able to effectively collaborate, all parties will experience success. It is even more important because the students are the ones who are able to benefit the most from the positive interactions (Starr & Foy, 2012). Teachers who understand and truly value where the parents are coming from, both academically and culturally, are able to foster academic and social success for the students (Gimbert, Desai, & Kerka, 2010). Parents should a true voice that is respected and listened to since they have first-hand experience dealing their children and are able to provide additional context and a different viewpoint for specific situations. They are direct source of information that teachers should utilize to ensure all decisions are made in the best interest of the child (Valle, 2011). Parents are a part of the IEP team and should be viewed and treated like an equal team member, not just a person that is legally required to participate and a check list person.

Possible Solutions

Parents have been trying to properly advocate for their children’s educational rights and futures, but sometimes are still met with great difficulties. One possible solution would be increasing the number of advocacy training programs that are already established and have seen positive results through their training programs. Another possible solution would to ensure that teachers and preservice teachers are trained on the best ways to handle children who have autism to avoid any unwanted and negative interactions in the classroom. Teachers and preservice teachers also need to proactive in making sure parents are truly included in the IEP process. Parents deserve the right to have their voices heard and any questions answered. Parents can feel intimidated to question teachers and can feel intimidated to ask questions about special education. Teachers need to do all they can to easy those feelings and work together to ensure success for the children they work with. Finally, teachers need to be aware that cultural differences and bias can unintentionally create negative relationships between parents, staff, and school systems. They need to be sure that they are leaving out their personal cultural views at the door.

References

Brown, H. K., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Hunter, D., Kelley, E., Cobigo, V., & Lam, M. (2011). Beyond an autism diagnosis: children’s fucntional independence and parents’ unmet needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1291-1302.

Burke, M. M. (2013). Improving parental involvement: training special education advocates. Journal of Disability Policy Studies , 225-234.

Gimbert, B., Desai, S., & Kerka, S. (2010). The big picture: focusing urban teacher education on the community. Kappan, 36-39.

Starr, E. M., & Foy, J. B. (2012). In parents’ voices: the education of children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 207-216.

Valle, J. W. (2011). Down the rabbit hole: A commentary about research on parents and special education. Learning Disability Quaterly, 183-190.

Bridging the Opportunity Gap in Special Education: Mastering the Florida Alternate Achievement Standards Through the Use of General Education Resources in a 3rd-5th Grade Self-Contained Classroom for Students with Mild to Severe Intellectual Disabilities

By Marissa Desiree Pardo

Abstract

As special education practices have evolved over the course of recent decades under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), many educators have sought to remedy the learning gaps that exist between students in general education and students in special education, particularly regarding students who are identified as having mild to severe intellectual or cognitive disabilities. Many methods have been introduced to close this gap, such as inclusion teaching methods, in which special education students spend most or all of their time in a general education classroom receiving assistance from a special education teacher, resource room teaching, a remedial and separate classroom in which students with educational disabilities are given specialized instruction in some content areas, and the self-contained or special separate classroom setting in which students with severe intellectual disabilities spend the entire day in the same classroom receiving specialized instruction from a special education teacher in all content areas. Despite the ever-evolving practices in the continuum of special education services being used to increase access to the grade-level text and curriculum for students with intellectual disabilities, minimal academic progress has taken place.

Many students with disabilities are served in a general education classroom, yet there are still questions raised on how to best close the knowledge gap for students with intellectual disabilities being served in a self-contained or separate special classroom setting. According to statistics from the National Center of Education Statistics (IES-NCES; 2018) completed in 2015-2016, 60% of students with disabilities between the ages 6–21 spent 80% of their school day or more in a general education classroom, whereas 20% of students with disabilities spent less than 40% of their day in general education classrooms. According to Siperstein, Glick, and Parker (2009), despite 30 years of legislative policies that were enacted to create an inclusive setting for students with cognitive disabilities, most students with intellectual disabilities are still excluded from general education classes and from the general social community within their schools. In fact, a national survey conducted by Siperstein, Parker, Noris Bardon, and Widaman (2011) of more than 5,000 students reported that only 10% of the students surveyed had a friend with intellectual disabilities. Based on these statistics, it is implied that students with intellectual disabilities are not being given a fair opportunity to meet certain academic standards based on youth and adult attitudes towards their inclusion in the general education populace or towards their participation in the general education curriculum. Unfortunately, the lack of appropriate educational provisions for these students based on the way they are perceived through these studies implies that they will be ill-equipped to navigate the real world upon completing school, which can be detrimental to their adulthood.

With such large gaps of knowledge in education and with inferior educational opportunities to promote academic growth for this population, many teachers, administrators, parents, and educational policy-makers have been challenged with the task of better accommodating students with intellectual disabilities for them to meet the rigorous academic standards of education. The goal was to reduce the number of students with disabilities (SWDs) in the self-contained special class setting and increase the number of SWDs in an inclusive setting.

The Miami-Dade County public school system implemented the Florida Alternate Achievement Standards, commonly referred to as Access Points. Access Points were educational standards that were academically challenging and provided accountability to the state regarding providing a free and appropriate education (FAPE) for students with significant cognitive disabilities. These standards mirrored the general education standards and their core intents and objectives for students of each grade level but were reduced in levels of complexity to serve the many needs of students in special education. Although these standards have given teachers a blueprint to better serve SWDs on a modified curriculum, it was the responsibility of the teacher to implement modifications and adaptations for each unique student to increase student academic achievement. The goal of these policies and laws were to implement the least dangerous assumption, or the idea that students with significant disabilities had the competency to learn, because to assume otherwise would result in less educational opportunities and expectations, inferior practices as compared to those in general education, and less opportunities for SWDs to attain an appropriate education (Jorgensen, 2005). Given the least dangerous assumption, it was possible that students with severe intellectual disabilities could make significant learning gains towards meeting the Florida Alternate Achievement Standards in counting money and calculating the value of money because of the study.

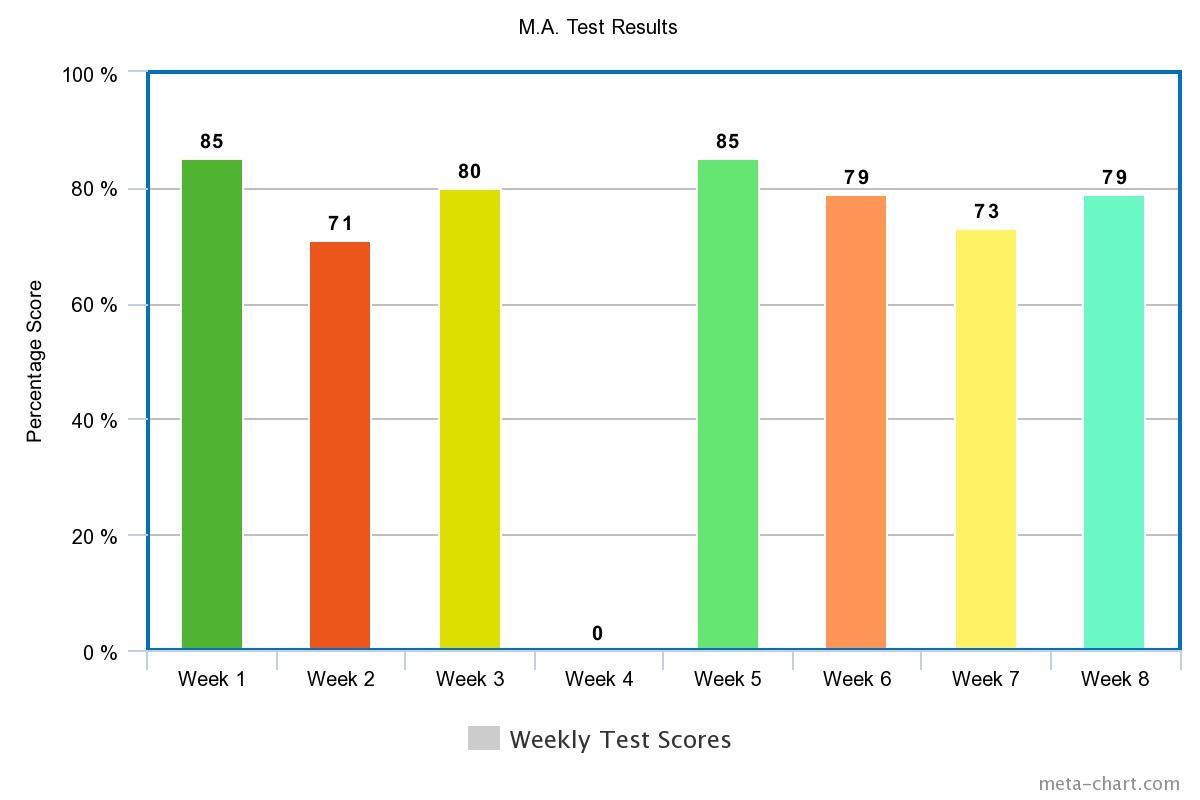

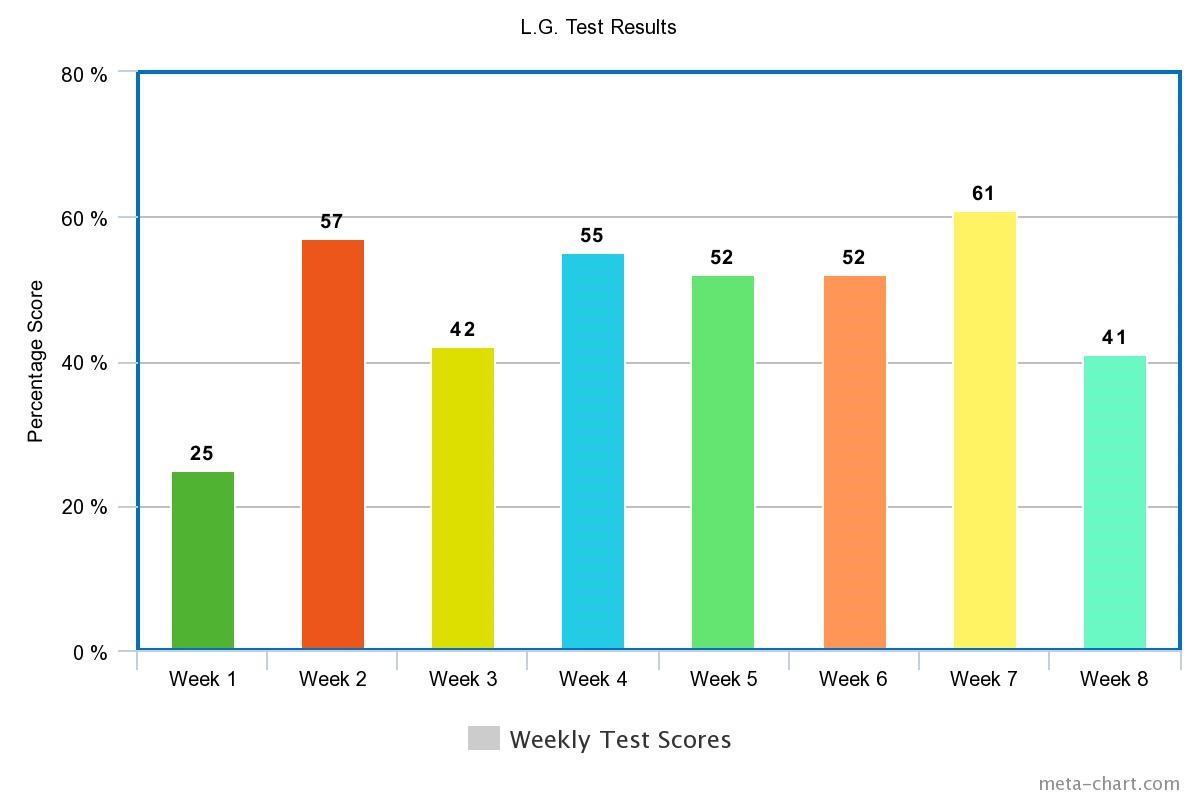

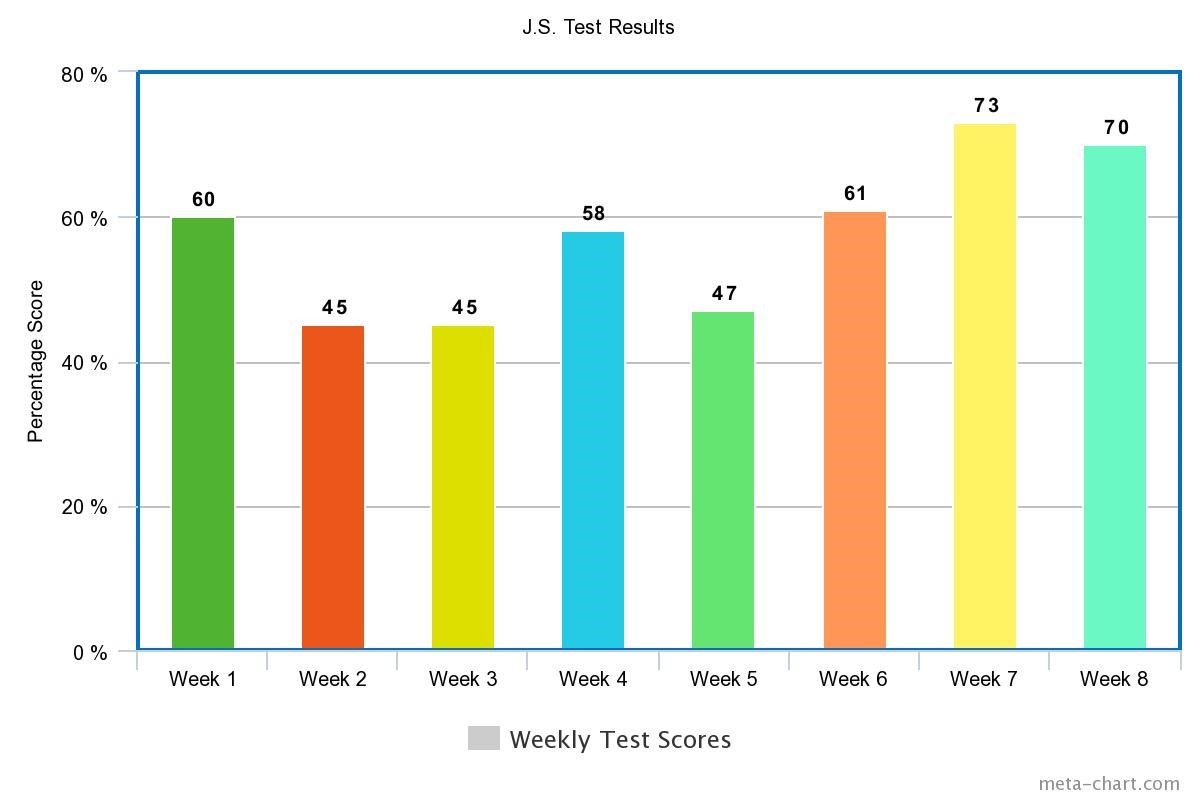

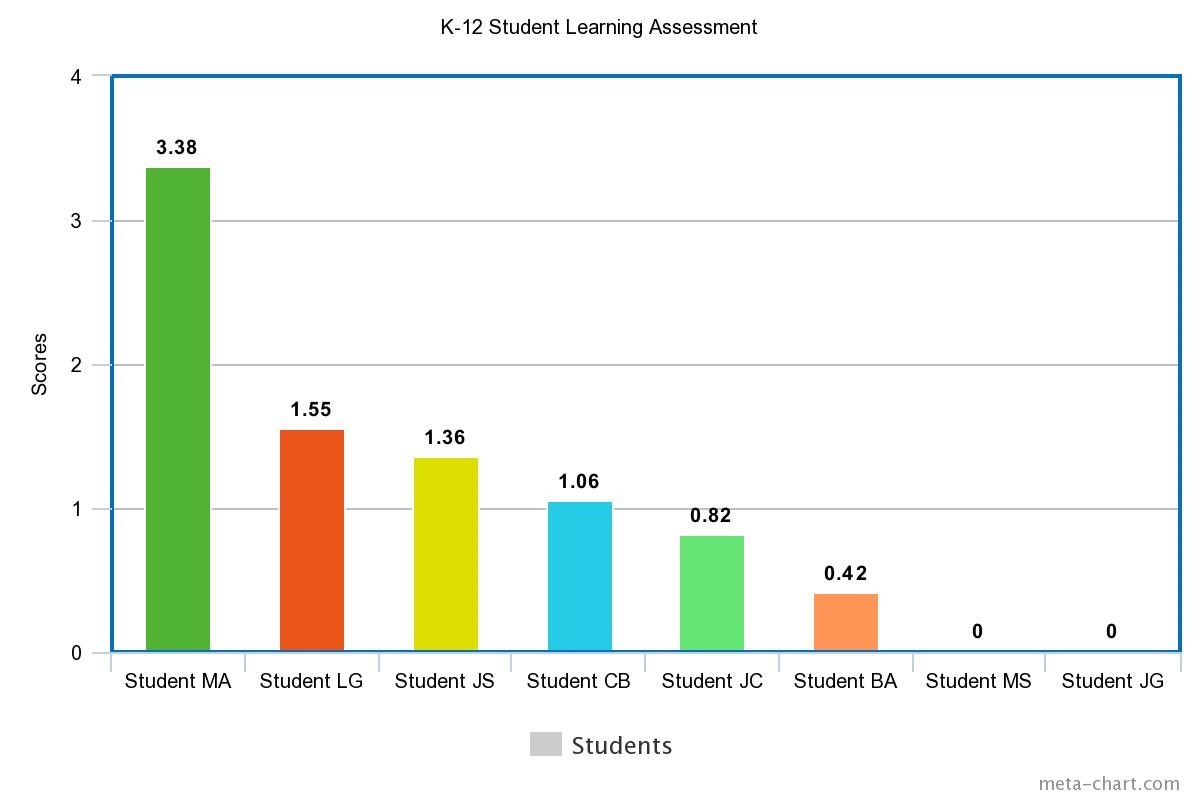

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the use of general education textbooks, resources, and grade-level texts, supplemented by classroom assignments that were tailored to the instructional levels of each individual student, would help students with mild to severe intellectual disabilities meet the Florida Alternate Achievement Standards in money and calculating the value of money. According to Hudson, Browder, and Wakeman (2013), access to grade-level texts for beginning readers or non-readers helped promote student engagement for students with moderate to severe intellectual disabilities, given that they were provided with accommodations and adaptations when necessary. While accommodations and modifications have been provided because of their Individualized Education Plans (IEP) and their current self-contained classroom placement, the 2018-2019 school year was the first year in which this student population was exposed and taught using the general education curriculum, textbooks, and resources alongside modified and leveled assignments. For this purpose, it was necessary for the action research to take place to measure whether the use of Mathematics general education textbooks from the Go Math! G3-G5 Student Edition series and other modified assignments from the Unique Learning System would increase student academic achievement towards meeting the Florida Alternate Achievement Standards.

Context

The action research took place in a Miami-Dade County public elementary school. Three third-grade students, two fourth-grade students, and three fifth-grade students identified as having mild to severe intellectual disabilities on their IEP’s participated in the study. The teacher progress monitored these students in the core content academic area of Mathematics. The standards being addressed in this study were based on acquiring the skills to comprehend the worth of United States dollars and cents and complete addition and subtraction problems involving money within a real-world scenario. The objectives of the instruction were to teach the students how to recognize that a decimal in money numbers indicated dollars and cents and that money can be calculated in dollars and cents in a real-world scenario. Despite the study including participants from three different grade levels, the Access Points standards correlated to one another.

The special education teacher conducting the study worked with another special education teacher who was currently teaching kindergarten through second-grade students with mild to severe intellectual disabilities in a self-contained setting. This teacher utilized the same practices used in this study and was responsible for implementing the use of the general education textbooks and resources while modifying the curriculum through the Florida Access Points Standards within their classroom. Both teachers convened weekly to discuss the findings and results of student academic progress throughout the study.

The school principal was notified, and permission was sought for this action research study. Parents were also informed about the action research plan and the focus on bridging the opportunity gap for students with mild to severe intellectual disabilities to increase academic achievement towards mastering the Florida Alternate Achievement Standards in Mathematics.

The necessary resources for conducting this action research included the physical or online versions of Miami-Dade County Public School’s general education Mathematics textbooks (Go Math! Student Edition) and other resources for grades 3-5. These resources were utilized to plan lessons and present instruction to the students. The teacher used the general education textbooks and resources for at least one-third of each lesson, for at least 20 minutes during the Mathematics block. For the remainder of each class period, the special education teacher used assessments and activities, primarily found in the Unique Learning System: Special Education Curriculumwebsite (2018). The assignments, materials, and resources found on this website were provided at the instructional level of each student, meaning the objectives of the assignments were the same, but the presentation and the complexity varied from student to student. The supplementary tasks and resources found on the Unique Learning System were used to provide differentiated instruction for the students based on varying instructional levels.

Literature Review

As special education practices have evolved over the course of recent decades under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), many educators have sought to remedy the learning gaps that exist between students in general education and students in special education, particularly regarding students who are identified as having mild to severe intellectual or cognitive disabilities. According to the Pennsylvania Association for Retarded Children (PARC) v. Pennsylvania (1972), a free and public education was provided for students who are intellectually disabled in the state of Pennsylvania because of parents challenging the exclusion of these students from public education. In the same year, a case titled Mills v. Board of Education (1972) arose and the district court found that violating due process and equal protection rights was a punishable offense. They ordered the provision of a free and public education to “exceptional children” after it became apparent that seven students of African-American descent and varying exceptionalities were denied access to education. Years later in 1997, IDEA was amended, highlighting the need for students to be in their least restrictive environment and mandating greater access for students with disabilities into the general curriculum. Changes were made to every student’s Individualized Education Plan to include a statement addressing how the student’s disability affected their involvement or participation in the general education classroom to prevent students from being staffed into special education without a probable cause. Despite the progress made in special education services and policies to increase access to the general education curriculum, especially for students with intellectual disabilities (InD), minimal academic progress has taken place to bridge learning gaps that exist. Although many students with disabilities are primarily served in a general education classroom for most or all the school day and various studies have been conducted to highlight their success in inclusion classrooms, there are still questions raised as to how to best close the knowledge gap for students with InD being served in a self-contained or separate special classroom setting. According to Etscheidt (2011), IDEA laws and accountability laws that are meant to ensure that teachers are providing students with disabilities a free and appropriate public education are insufficient, citing that district-wide accountability, higher standards for teachers and students, and an individual responsibility can determine whether the education is appropriate and can benefit students with disabilities in accessing the general curriculum.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the use of general education textbooks, resources, and grade-level texts, supplemented by modified classroom assignments from the Unique Learning System: Special Education Curriculum website tailored to the instructional levels of each individual students, helped students with mild to severe InD meet the Florida Alternate Achievement Standards. The action research will take place in a public elementary school located in Miami-Dade County. Three third-grade students, two fourth-grade students, and three fifth-grade students identified as having mild to severe InD on their IEP’s participated in the study. The teacher progress monitored these students in the core content academic area of Mathematics. Through this research, it was determined whether the use of these materials narrowed the achievement gap between students with mild to severe InD in the self- contained classroom setting and their non-disabled peers in a regular classroom setting, as monitored by monthly pretests and posttests.

Qualitative Perceptions of Teachers About Teaching

Students with Intellectual Disabilities

To begin to unravel why the deficits in learning are more prominent for students with InD in a self-contained classroom setting as compared to their non-disabled peers in the general education setting, it is important to consider whether these students are being effectively served in their current placements. A study conducted by Kahn, Sami and Lewis (2014) measured teacher perceptions and preparedness for teaching students with disabilities. These perceptions and preparations were ultimately deciding factors in the success or failure of these students in a general education science classroom. A national survey was conducted with 1,088 K-12 science teachers as participants (Kahn, Sami & Lewis, 2014). Throughout the study, it was agreed upon that the participating science teachers felt as if they were ill-prepared to teach students with disabilities, ultimately resulting in average or poor instructional knowledge. This unpreparedness stems from gaps in their own knowledge in effective teaching strategies to utilize when working with students with disabilities in their classrooms, along with certain barriers that possibly inhibited students with disabilities from succeeding in a general education setting, such as the need for a lower pupil to teacher ratio, the need for modifications, and the extensive time it takes to create materials for each student that is tailored to their needs. It was concluded that a lack of training and preparation, a lack of support, and pressure for students to do well on state assessments ultimately facilitated negative attitudes from science teachers working with students with disabilities. It was believed by all the participating pre-service and in-service teachers involved that more training on working with students with disabilities would bridge their own gaps of knowledge and increase the rate of success for these students within their classrooms (Kahn, Smai, & Lewis, 2014). Through this support and training, teachers can effectively provide explicit and systematic instruction to their students with InD. Explicit and systematic instruction is defined as a practice that is evidenced-based in increasing the reading and math levels through activities that build foundational skills, having a large impact on student outcomes and academic progress (Gersten et al., 2008, 2009).