Table of Contents

-

Book Review: A Force for Change (Author: John Paul Kotter). By Maria Ibarra

-

Montessori for Children with Learning Differences. By Joyce Pickering, MA, SLP/CCC, HumD

-

Book Review: What Great Principals Do Differently: 18 Things that Matter the Most (Author: Todd Whitaker). By Norma Samburgo

-

An Investigation of Whether Teachers Find Technology or Manipulatives More Effective For Teaching Students With Special Needs. By Shari Caranante

-

Book Review: Strengths Based Leadership – Great Leaders, Teams, and Why People Follow (Author: Tom Rath). By Rebecca A. Timmer

-

A Survey of Special Educational Services Delivered to the Individuals with Disabilities at Special Education Institutes and Centers in Kingdom of Jordan. By Mezyed A. S. Adwan, Ph.D.

-

Special Education Legal Alert. By Perry A. Zirkel

-

Latest Employment Opportunities Posted on NASET

-

Acknowledgements

By Louris Otero

Young students are lively and active and need movement while they learn (Moyles, 2015). However, there are certain learning activities that require students to remain seated or keep their physical motions to a minimum. Many of today’s classrooms offer alternative learning activities and seating solutions for students with and without diagnosed sensory integration issues. Many new techniques have been found to useful for students with specific needs and also help to serve the needs of the wider population. The use of fidget toys, wiggle seats and other tools based on occupational therapy offer students a possible solution to the need for movement while remaining attentive.

Occupational therapy supports students with disabilities in the classroom by looking at academic goals and functional goals (Hutchinson & Villeneuve, 2012). It helps to remove physical and attitudinal barriers to participation and recommends changes to activities and assistive technology as strategies to help students be successful regardless their disability (Case-Smith, Rogers, & Johnson, 2005). Additionally, the study by Hutchinson and Villenueuve (2012) showed that students benefit from having educators and occupational therapists collaborate on treatment plans and academic and functional goals.

The purpose of this action research study was to determine whether the use of occupational therapy assistive technology and fidget toys during whole class instruction and independent work helped improve on-task behavior. This action research was important because Universal Design for Learning supports making assistive technology available to all students because all students, regardless of capabilities will benefit from using them to remove barriers to the curriculum.

The action research took place in a 1st grade classroom in a private school located in Coconut Grove, Florida. The participants were 15 first graders. Permission for participation was obtained from parents or the legal guardians of all participants. All students were provided with the opportunity to make use of various fidget toys during whole class instruction and independent work. The teacher collaborated with the occupational therapist to provide necessary materials for the study and related expertise in the proper use of the technologies. The following data was collected: choice of whether or not a fidget toy was used, a teacher checklist of whether or not the student was on-task, simple student pre and post questionnaire meant to self-determine accuracy of listening comprehension. Student work was also collected during the study.

Literature Review

Villeneuve and Hutchison (2012) looked at the effect of collaboration between the occupational therapist and the educator during the delivery of services on the goals and expectations of two students. There were two participants, 6-year old boy with Autism and a 6-year old female with a chromosomal abnormality. This was a qualitative study consisted of ethnographic observations, documents, interviews and the Socio-Cultural Activity Theory (Engestrom, 2001). The results of the study showed that collaboration between the educator and occupational therapist supported planning, transitions between services and learning, and accountability regarding recommendations and programming for students.

Miller, Coll, and Schoen (2007) tested the effectiveness of occupational therapy – sensory integration in children with sensory modulation disorder (SMD). Twenty-four children participated in the study: five with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), 3 with a diagnosed learning disability, 1 with anxiety disorder and 15 without any previous diagnosis.

A pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) tested the effectiveness of occupational therapy (OT) and sensory integration (SI) techniques on children with sensory disorders. Twenty-four children with sensory disorders were assigned 1 of 3 treatments: (a) occupational therapy, (b) sensory integration, (c) activity protocol, and (d) no treatment.

Pretests and posttests were given to measure physiology, behavior and, sensory and adaptive functioning. Results concluded that OT-SI was effective in children with SMD more so than no treatment, or a placebo treatment (activity protocol).

This study in this article evaluated the effect of stability balls on in-seat and on-task behavior, and teacher and student perception of stability balls (Fedewa & Erwin, 2011) . The study Fedewa and Erwin (2011) was conducted across 3rd through 5th grade classrooms in an elementary school in rural Kentucky on 76 students. Eight students with a high or very high probability of ADHD were observed. Students used stability balls in place chairs for seating. Baseline data was collected for 2 weeks prior to beginning the study. The study lasted 12 weeks. In-seat on-task behavior improved. On average, students were seated 94% of the time and remained on-task for 80% of the time. Again, this article will inform the current study in that an occupational therapy tool will be offered to the students in an effort to study its effectiveness on on-task behavior in 15 first grade, female students.

This study by Devlin, Healy, Hughes, & Leader (2011) compared and examined the effects of sensory integration theory and behavioral intervention on the rates of challenging behavior in 4 students with autism. There were 4 male participants with a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Participants were chosen because they had a history of challenging behavior. Participants attended schools that employ applied behavior analysis. All participants received speech and language therapy, along with corresponding occupational therapy including the use of sensory integration devices such as a net swing, a trampoline, a therapy ball, a bean bag, and various chewable and small tactile devices. Results showed that challenging behaviors were reduced with the use of behavioral intervention more so than with the use of sensory integration intervention (Devlin, et al., 2011). The study in this article will inform the current action research in that by offering fidget toys as a means to self-regulate, the students will be able to reduce the incidence of challenging or off-task behaviors. Although the study in this article suggests that using behavior intervention is more effective (Devlin, et al., 2011)

This study in this article is centered on the question of distractibility and whether or not it is caused by increased competition in sensory cortex, decreased capacity of cognitive control, or deficient feedback from control areas to sensory regions (Friedman-Hill, Gex, Leibenluft, Pine, Ungerleider, & Wagman, 2010). This study was conducted on 3 groups of students: 15 children with ADHD ages 8-13, 14 typically developing children aged 9-13, and 15 healthy adults aged 22 – 42. Participants were shown a photo that would morph from the face of an ape to that of a woman while other images meant to serve as distracters flashed in different places on the screen. Participants indicated the changes in the face while distractors flashed. Results found that healthy adults had substantially lower perceptual thresholds than healthy children (Friedman-Hill, et al., 2010). There was no difference in the results found among children with ADHD and healthy children (Friedman-Hill, et al., 2010). This article will inform the current study because of the information regarding distractibility. The focus of the current investigation is to reduce distractions with the use of fidget toys and in essence, keep the student focused on the lesson by satisfying the need to do something with their hands while they listen.

This study in this article measured whether or not there are differences in sensory processing behaviors in children with ASD and neuro-typical children (Tomcheck & Dunn, 2007). It measures the differences in sensory processing domains in children with ASD. Participants consisted of 400 children diagnosed with ASD, 1,075 children ranging in ages from 3 to 10 years old who were not receiving special education services. The Short Sensory Profile was administered to each participant. Children with ASD were reported to have sensory impairments, whereas typically developing children did not (Tomcheck & Dunn, 2007). Significant differences were found in performance when comparing children with ASD and typically developing counterparts (Tomcheck & Dunn, 2007). This article will inform the current action research by offering information on the performance of typically developing children and sensory processing.

This study by Collins and Dworkin (2011) looked to measure the effectiveness of a weighted vest attention to task. Twenty-five, 2nd grade students with difficulty attending while learning in general education classrooms. Data were taken of students while on-task, with and without the weighted vest. Results indicate that vests were not effective in increasing time on task (Collins & Dworkin, 2011). Results should be taken cautiously due to the small sample size and participant selection process.

Although the weighted vests were not effective in the study in this article, the information may prove useful in administering the current study. The sample in the current study will also be small, but a different OT device will be used hoping to yield effective results in focus and on-task behavior.

The purpose of this study by Bose and Hinojosa (2008) was to explore the interactions of occupational therapists with teachers and other school personnel in Kindergarten through 2nd grade inclusive education classrooms in the New York City metropolitan area. Fliers were sent out via mail to a list of occupational therapists working in the NYC metropolitan area. Thirty inquiries to participate were received and six were selected based on a specific criteria. In-depth interviews of the occupational therapists were conducted over a 20-week period. Participants viewed their experiences with faculty as difficult (Bose & Hinojosa, 2008). Problems included time constraints, lack of communication and teacher receptiveness. All occupational therapists noted professionalism of interactions and found collaboration valuable (Bose & Hinojosa, 2008). This article will inform the current study because of the collaboration that will occur between the classroom teacher and the occupational therapist while the action research is being conducted. During the action research the teacher will consult the OT for materials and best practices when offering students fidget toys, and how best to collect and analyze data.

The purpose of this study was to examine the prevalence of and relationship between sensory processing difficulties and behavior difficulties (Fox, Snow & Holland, 2014). Participants were a sample of 38 children involved in a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service and Schools Early Action Program, which is a multi-modal early intervention program for children from Preparatory1 (Prep) to Year 3 (i.e. approximately ages 5–8) who had been identified as being at risk of developing conduct disorder. Behavioral problems were assessed using the parent-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire along with the 36-item Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory, which is a parent-rating scale that screens for disruptive behavior. Sensory processing difficulties were assessed using the parent-reported Short Sensory Profile. Also, the Children’s Communication Checklist was used to screen for language impairment. The study in this article used face-to-face meetings for the purpose of administering the measures Fox, et al., 2014). A correlation was found between sensory processing difficulties and the prevalence of disruptive behavior (Fox, et al., 2014). This article will inform the current action research study in that the students in the investigation are within the same age group. The hope is that the use of an occupational therapy device such as fidget toys will thwart behavioral difficulties.

In the current study, students were offered fidget toys to use while listening and participating in a whole-class activity or instruction. The goal of this study was to determine if students with or without SMD benefitted from the use of fidget toys. Additionally, these studies regarding the benefits of collaboration supported the action research because of the collaboration that occurred between the classroom teacher and the occupational therapist while the action research conducted. The teacher consulted the OT for materials and best practices when students were offered fidget toys.

|

Action Plan/Methods |

|

|||

|

Name: Louris Otero School: Carrollton School of the Sacred Heart

|

|

|||

|

Research Question(s): What is the effect of occupational therapy assistive technology (such as fidget toys) on the on-task behavior of elementary students during whole-group and independent instructional time?

|

|

|||

|

Intervention: Describe the intervention you will implement to accomplish the outcomes you seek for your students?

The intervention consisted of making various fidget toys available for students to use during whole-group instruction or activity. Students were allowed to choose from fidget toys provided by the in-house occupational therapist. Silent fidget toys are self-regulation tools that keep restless bodies, fingers, and feet occupied. Silent fidget toys can be squishy toys made of rubber, tiny bean bags for squeezing, coiled rings for pulling, tension balls, Silly Putty for squeezing and pinching, or knead-able erasers. In this particular study, a variety of fidget toys were used.

The goal was to give students an opportunity to “fidget” or do something with their hands to keep them focused and on-task. The student was free to play with the toy of their choice in any way that they deemed appropriate. This play was unstructured because the point was to satisfy a sensorial need in an effort to keep the student on task. Time Line: (separate sheet) Data collection took place over an 8 week period. Data collection started in January and ended in early late March/early April 2017.

|

|

|||

|

Data Collection: Describe the specific approaches you will use to collect data before, during, and/or after your intervention. You need to “triangulate” your data; thus, you need at least 3 different data sources (e.g., tests, observations, interviews). Also, be specific about what each data source measures (e.g., you are using a test that measures reading comprehension or using observation to tally bullying behaviors). Next, describe the type of data that you obtain with each source (e.g., scores from a test of subtraction facts or a frequency of bully events observed).

Data Source 1: Prior to implementing the intervention, it was explained that fidget toys were available for everyone to use during a lesson that required listening comprehension and the need to remain on-task. The teacher observed and noted whether or not students chose to use toys. Students participated in a survey of their behavior prior to using fidget toys during the lesson and after the intervention was completed.

Data: Pre and post survey responses from students

Data Source 2: Weekly, at the beginning of the lesson, students’ prior knowledge was assessed during a group discussion. Student work was collected. Students completed a teacher-created survey to self-assess on-task behavior.

Data: Weekly teacher-created survey

Data Source 3: Teacher tallied the number of students engaged in off-task behaviors during each lesson. The number of off-task behaviors will be averaged weekly.

Data: Weekly checklist of on or off-task behavior for 8 weeks. Checklist to keep track of students’ choices of toys.

|

|

|||

|

. |

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

Time Line (use separate form): The Time Line must include length of intervention and when materials (if needed) are prepared, when persons are notified and/or permissions are sought, and when you plan to collect all data – be very specific |

|

|||

|

|

|

January 23, 2017 –sent permission letter home with students for signature

January 25, 2017

Week of January 30, 2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

Week of February 6-10, 2017 Week of February 13-17, 2017 Week of February 20-24, 2017 Week of February 27-March 3, 2017 Week of March 6-10, 2017 Week of March 13-17, 2017 Week of March 20-24, 2017 Week of March 27-31, 2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

Week of April 3, 2017

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Findings, Limitations, and Implications

Data Analysis

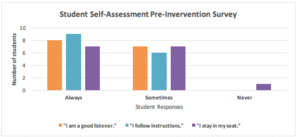

The data collected were analyzed by reviewing the results of the student self-assessment survey, the teacher checklist of students engaged in off-task behaviors, and the teacher-created exit tickets that allowed students to determine whether they had listened better with or without the fidget toy. In the first measure, the students were given a short survey conducted at the onset of the intervention. The first measure consisted of a short 3-question survey of the students used to help them assess their on-task behaviors:

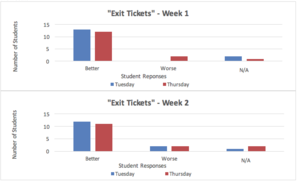

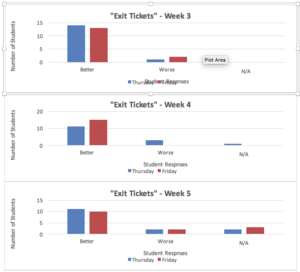

The second measure consisted of a post-lesson question in the form of an “exit ticket” posed to the students. This question was used to self-assess their on-task behavior after having used a fidget toy in an effort to curb off-task behaviors. Students that chose not to use fidget toys were also given the “exit ticket” to fill out.

The third measure consisted of a simple survey administered at the end of the application of the intervention. This survey helped the students self-assess their on-task behaviors in relation to their use of the fidget toy. In the meantime, the teacher kept a checklist of students engaged in off-task behaviors.

Findings

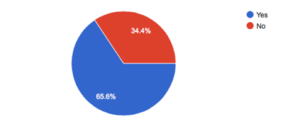

Figure 1. Self-assessment of students to self-determine listening skills, ability to follow instructions and remain in their seats

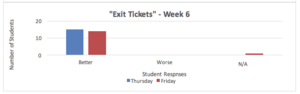

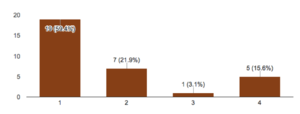

Figures 2-9.Bi-Weekly post-invention/post-instructional “Exit Tickets” to self-determine listening skill.

*The “Not applicable” designation was assigned to those students that chose not to use a fidget toy on that given day.

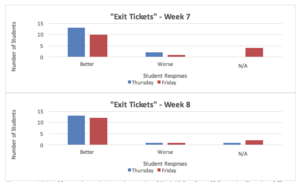

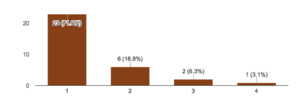

Figure 10. Post-intervention self-assessment survey.

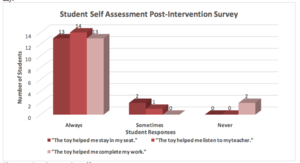

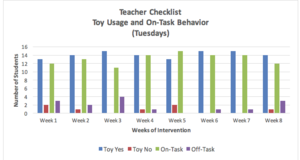

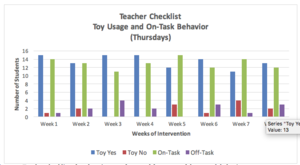

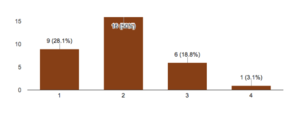

Figure 11.Teacher checklist of students’ usage of toys and frequency of the on-task behavior.

Figure 12.Teacher checklist of students’ usage of toys and frequency of the on-task behavior.

On-task behavior is defined as a student’s engagement in behaviors as expected by the teacher and as outlined by the classroom instruction.

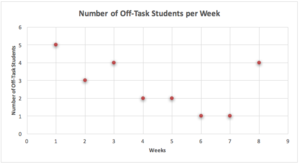

Figure 13. Number of students that were off-task per week during the intervention.

The findings as illustrated in Figures 1-13 show that students thought that they were “good listeners” already before, during and after the intervention. The teacher was able to correlate those results using the checklist to record observations of students’ behavior and whether or not they chose to use a fidget toy. Based on the teacher observations, the fidget toys did not increase or decrease student engagement. This is due in part to the small sample group and its limitations which will be discussed below.

Pre and Post Intervention Student Survey of On-Task Behavior. Prior to implementing the intervention, it was explained that fidget toys were available for everyone to use during a lesson that required listening comprehension, and the need to remain on-task. The teacher observed and noted whether or not students chose to use toys. Students then participated in a survey of their behavior prior to using fidget toys during the lesson and after the intervention was completed. This simple survey consisted of three positive statements about their ability to be good listeners, follow instructions, and stay in their seats. The students were asked to circle the response that best matched their behavior, always, sometimes, or never. Figure 1 shows eight out of 15 students thought they were always good listeners pre-intervention. Nine out of 15 students thought they always followed directions, and seven out of fifteen students circled always when describing their ability to stay in their seats. Roughly half of the class thought they were good listeners, followed instructions, and stayed in their seats sometimes. Interestingly, no one circled never being a good listener or following instructions, but there was one outlier who circled never for staying in their seat.

The Post-Intervention Student Survey gave the students another opportunity to self-assess once the 8-week intervention was completed. Students were given a teacher-created survey with three positive statements about their behavior while using a fidget toy: The toy helped me stay in my seat, listen to my teacher, and complete my work. They students then circled the answer that best matched their behavior: always, sometimes or never. Students, with the exception of one or two, overwhelmingly chose always to describe their listening, their ability to stay in their seats and complete their work. Only two students chose Never to describe how well they were able to complete their work with a fidget toy. This may have occurred because the student either did not use a fidget toy or perhaps they misunderstood the statement. These students are young and perhaps lack the self-awareness needed to decide whether or not a fidget toy might be useful.

Post Lesson Exit Ticket. Weekly, at the beginning of the lesson, students’ prior knowledge was assessed during a group discussion. Student work was subsequently collected and students then completed a teacher-created survey to self-assess on-task behavior at the end of the lesson. This simple survey consisted of one question asking students to decide if they were better or worse listeners with a fidget toy. These data were collected twice per week for a total of eight weeks. Most students decided that they were better listeners when they used a fidget toy. Very few students considered themselves worse listeners when they used a fidget toy. There may have been a tendency to answer positively because they enjoyed playing with the toys regardless of the lesson or activity they were supposed to be engaged in at the time. In other words, if a student answers that the fidget toy helped, then the teacher will continue to let them use it during instructional time. Based on teacher observations, this is just typical behavior for the age group in the sample.

Frequency of Off-Task Behavior. Figures 11- 13 illustrate the frequency of off-task behavior during the intervention. The typical week showed that one to three students exhibited off-task behaviors such as talking with other students during instructional time or turning in incomplete assignments. Week one and three showed that five and four students, respectively, were off task during instructional time. The reason for the off-task behavior varied from lack of interest to distraction due to the fidget toy itself, based on teacher observations. Students were frequently redirected to turn their attention to lesson and students typically complied.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The study was conducted during an eight-week span. During the course of the school day, there are many scheduled interruptions throughout the week such as assemblies, religious services, days off from school, and absenteeism. In addition to the interruptions, it became increasingly evident that the fidget toys could also serve as distractions, as observed by the teacher. The students were eager to use the toys, but at times the playing distracted the students from listening, and as a result, caused a disruption to the lesson. Initially, the intervention was to be administered daily, but the teacher quickly noticed the potential for disruption and only administered the intervention twice per week. The teacher also questioned the honesty of the student responses to the survey as they thought the toys were helping them listen and stay on task, but the teacher observed otherwise. This research might prove more interesting results if conducted with older students with better self-awareness.

Implications

Since this intervention, the use of and popularity of fidget toys has crossed over from being used strictly by students with sensory integration disorder and attention deficit disorder to neurotypical students. This causes an issue for teachers and students alike because of the potential for disruptions in classroom management. It potentially lessens the positive effects of the fidget toys as a method of therapy. By the same token, the use of fidget toys by most, if not all students, makes them accessible to all without the fear of appearing or feeling different from other students. If this intervention is applied with fidelity and the novelty is allowed to wear off, then it could be useful in the classroom as stress relievers and means of finding the movement that many students seek while sitting and listening.

Dissemination

The findings of this study were shared with my school administrators during a weekly Academic Team Meeting. Additionally, the findings were shared with the faculty of the Primary School during the weekly faculty meeting. The results of the study were also shared with members of the faculty at-large at a professional development day conducted at the school. Finally, results of the study were shared with Florida International University (FIU) graduate students during a poster board session.

References

Case-Smith, J., &Rogers, J. (2005). School-based occupational therapy. In J. Case-Smith (Ed.)

Occupational therapy for children (5th ed., pp. 795-824) St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby.

U.S. Department of Education. (2014, October 29). Building a Legacy: IDEA 2004. Retrieved from ED.gov: idea.ed.gov/explore/home

Wasatch School District . (2014, October 30). Video Surveillance Policy. Retrieved from Wasatch School District: www.wasatch.edu/cms/lib/UT01000315/Centricity/Domain/2/Article_III_Video_Surveillance_Policy.pdf

Alicia F. Saunders, K. S. (2013). Solving the Common Core Equation: Teaching Mathematics CCSS to Students with Moderate and Severe Disabilities. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 24-33.

An Overview of Related Services Under IDEA. (2013, 12 1). Retrieved from Education.com: www.education.com/print/Ref_Related_Services/

ASCD. (n.d.). The Common Core State Standards Initiative. Retrieved from ASCD.org: www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/siteASCD/policy/CommonCoreStds.pdf

Baker, L., Dreher, M. J., Shiplet, A. K., Beall, L. C., Voelker, A. N., Garrett, A. J., . . . Finger-Elam, M. (2011). Children’s comprehension of informational text: Reading, engaging, and learning. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 197-227.

Beecher, M., & Sweeny, S. M. (2008). Closing the Achievement gap with curriculum enrichment and differentiation: One school’s story. Journal of Advanced Academics, 502-530.

Behrent, M. (2011). In Defense of Public Education. Retrieved from New Politics: newopol.org/content/defense-public-education

Belva C. Collins, J. K. (2010). Teaching Core Content with Real-Life Applications to Secondary Students with Moderate and Severe Disabilities. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 52-59.

Blaska, J. K. (1996). Using children’s literature to learn about disabilities and illness. Moorehead, MN: Practical Press.

Bodrova, D. J. (2012, January). Play and Children’s Learning. Retrieved from National Association for the Education of Young Children : www.naeyc.org/files/yc/file/201201/Leong_Make_Believe_Play_Jan2012.pdf

Brown, J. (2013, January 22). National dropout, graduation rates improve, study shows. Retrieved from USATODAY.com: www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/01/22/education-high-school-dropout-rate/1855233/

Bush, T. (2007). Educational leadership and management: theory, policy, and practice. South African Journal of Education, 391-406.

Butrymowicz, S. (2010, September 1). National crisis: Not much training for some special-ed teachers. Retrieved from The Hechinger Report, Independent Educational News: hechingerreport.org/content/national-crisis-not-much-training-for-some-special-ed-teachers_4189/

Cancio, PhD1, E., Albrecht , S., & Jones , B. (2014). Combating the Attrition of Teachers of Students With. Intervention in School and Clinic 2014, Vol. 49(5), 306-312.

Carolan, J., & Guinn, A. (2007). Differentiation: lessons from master teachers. Educational Leadership, 64(5), 44-47. Retrieved 12 04, 2016, from www.ascd.org/premium-publications/books/110058e4/chapters/Differentiation@-Lessons-from-Master-Teachers.aspx

Caruana, V. (2015). Accessing the Common Core Standards for Students with Learning Disabilities: Strategies for Writing Standards-Based IEP Goals. Preventing School Failure, 237-243.

Collins, B. C., Karl, J., Riggs, L., Galloway, C. C., & Hager, K. D. (2010). Teaching Core Content with Real-Life Applications to secondary Students with Moderate to severe disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 43(1), 52-59.

Constable, S., Grossi, B., Moniz, A., & Ryan , L. (2013). Meeting the Common Core State Standards for Students with Autism the Challenge for Educators. Teaching Exceptional Children , 45(3), 6-13.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010, Oct). What we can learn from Finland’s successful school reform. Retrieved from National Education Association: www.nea.org/home40991.htm

Darrow, A.-A. (2014). Applying Common Core Standards to Students with Disabilities in Music. General Music Today, 33-35.

DeMik, S. A. (2008). Experiencing Attrition of Special. Valparaiso University.

Development, T. O. (2012, March 13). OECD calls for new approach to tackle teacher shortage. Retrieved from OECD: better policies for better lives: www.oecd.org/newsroom/oecdcallsfornewapproachtotackleteachershortage.htm

Devlin, S. H. (2011). Comparison of behavioral intervention and sensory-integration therapy in the treatment of challenging behavior. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1303-1320.

D’Orio, W. (2013). Finland is #1!,Finland’s education success has the rest of the world looking north for answers. Retrieved from Administrator Magazine: Curriculum: www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp

Dr. Moira Konrad, D. S. (2014). Setting Clear Learning Targets to Guide Instruction for All Students. Intervention in School and Clinic, 76-85.

Dr. Sarah J. Watt, J. R. (2016). Teaching Algebra to Students with Learning Disabilities: Where Have We Come and Where Should We Go? . Journal of Learning Disabilities, 437-447.

Duncan, A., & Posny, A. (2010, Nov). Thirty-Five Years of Educating Children With Disabilities Through IDEA. Retrieved from ED.gov: www2.ed.gov.print/about/offices/list.osers/idea35/history/index.html

Dworkin, A. &. (2011). Pilot study of the effectiveness of weighted vests. American Journal of Occupational Therapists, 65(6), 688-694. doi:10.5014/ajot.2011.000596

Edutopia: Finland’s Formula for School Success (Edcation Everywhere Series). (2012, January 24). Retrieved from Edutopia.org: www.edutopia.org/reduction-everywhere-international-finland-video

English, J. (2013, Oct 24). US Teacher Gets Finnish Lesson in Optimizing Student Potential, Part 2. Retrieved from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) : oecdinsights.org/2013/09/24/us-teacher-gets-finnish-lesson-in-optimizing-student-poetential-part-2/

Essex, N. L. (2008). School Law adn he Public Schools: A Practical Guide for Educational Leaders. Boston: Pearson.

Fedewa, A. &. (2011). Stability balls and students with attention hyperactivity concerns: Implications for on-task and in-seat behavior. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(4), 393-399. doi:10.5014/ajot/2011.000554

Finland, T. T. (2008). Teacher Education in Finland. Helsinki: Forssan Kirjapaino.

Fox, C. S. (2014). The relationship between sensory processing difficulties and behavior in children aged 5-9 who are at risk of developing conduct disorder. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 19(1), 71-88. doi:10.1080/13632752.2013.854962

Friedman-Hill, S. W. (2010). What does distractibility in ADHD reveal about mechanisms for top-down attentional control? Cognition, 115(1), 93-103. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2009.11.013

Friend, M., & Bursuck, W. D. (2010, July 20). The Special Education Referral, Assessment, Eligiblity, Planning, and Placement Process. Retrieved from Education.com: www.education.com/reference/article/special-education-referral-assessment/

Fullan, M. (2001). Leading in a Culture of Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Gale Encyclopedia of Education: special Education: Preparation of Teachers. (2013, 11 23). Retrieved from Answers.com: www.answers.com/topic/special-education-preparation-of-teachers

Gray, J. (2008, 12). The implementation of differentiated instruction for learning disabled students included in general education elementary classrooms. La Verne, California, United States.

Hancock, L. (2011, September). Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from Smithsonian.com: www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/Why-Are-Finlands-Schools-Successful.html

Hayes, G., Gardere, L., Abowd, G., & Truong, K. (2008). CareLog: A Selective Archiving Tool for Behavior Management in Schools. CHIP 2008 Proceedings-Tools for Education, (pp. 685-694). Florence .

Heavey, S. (2013, Nov 6). U.S. Poverty rate remains high even counting government aid. Retrieved from Business & Financial News, Breaking US & International News/ Reuters.com: www.reuters.com/assets/print?aid=USBRE9A513820131106

Hesselbein, F., & Shinseki, G. E. (2004). Be-Know-Do: Leadership the Army Way. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hilyard, V. M. (2004, Fall). Teachers’ understanding and use of differentiated instruction in the classroom. Saint Louis, Missouri, United States.

Hinojosa, P. &. (2008). Reported experiences from occupational therapists interacting with teachers in inclusive early childhood classrooms. American Journal of Occupational Therapists, 62(3), 289-297. doi:10.5014/ajot.62.3.289

History: twenty Five Years of Progress in Educating Children With Disabilities through IDEA. (n.d.). Retrieved from U. S. Office of Special Education Programs: www.ed.gov/offices/osers/osep

Huff Post. (2012, 01 27). Best Education in the World: Finland, South Korea Top Country Rankings, U.S. Rated Average. Huff Post.

IES. (2013, 04 11). Fast Facts. Retrieved from National Center for Educational Statistics: nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=64

Irma Suovirta, R. H. (2013, November 15). Statistics Finland: Pre-primary and comprheensive school education 2013. Retrieved from Statistics Finland: www.stat.fi/til/pop_2013_2013-11-15_tie_001_en.html

Itkonen, T., & Jahnukainen, M. (2009, August 8). Disability or Learning Difficulty? constructing Special Eduaiton Students in Finland and the United States. Retrieved from All Academic Research: citation.allacademic.com/meta/p_mla_apa_research_citation/3/0/7/6/5/pages307659/p307659-1.php

J. McLeskey, N. T. (2004). The Supply of and Demand for Special Education Teachers: A Review of Research Regarding the Chronic Shortage of Special Education Teachers. The Journal of Special Education, 5-21.

Kamenetz, A. (2014, October 30). UPDATED: New Details On Bill Gates’s $5 Billion Plan To Film, Measure Every Teacher. Retrieved from Creative Conversations: www.fastcompany.com/3007973/creative-conversations/updated-new-details-bill-gatess-5-billion-plan-film-measure-every-tea

Kelley, S. (2014, October 30). Interview with Shawn Kelley. (A. Ivie, Interviewer)

Key Provision on Transition: IDEA 1997 compared to H.R. 1350 (IDEA 2004). (n.d.). Retrieved from National Center on Secondary Education and Transition: www.ncset.org/premium-publications/related/ideatransition.pdf

Kieffer, M. J. (2013). Morphological awareness and reading difficulties in adolescent Spanish-speaking language minority learners and their classmates. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 44-53.

Kinlan, C. (2011, January 21). Rethinking Special Education in the U. S. Retrieved from Hechinger Report: hechingerreport..org/content/rethinging-special-education-in-the-u-s

Konrad, M., Keesey, S., Ressa, V., Alexeeff, M., Chan, P., & Peters, M. (2014). Setting Clear Learning Targets to Guide Instruction for all students . Intervention in School and Clinic, 50(2), 76-85.

Labor, D. o. (2013, 09 28). U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Web: stats.bls.gov. Retrieved from Info please: www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0104719

Lepi, K. (2013). How 12 Countries Spend Education Money (And If It Makes A Difference). Edudemic; connecting education & technology.

Levy, H. M. (2008, Mar-Apr). Meeting the needs of all students through differentiated instruction: helping every child reach and exceed standards. The Clearing House, 81(4), 161-164. doi:10.3200/tchs.81.4.161-164

Logan, B. (2008). Examining differentiated instruction: Teachers respond. Research in Higher Education Journal, 1-14.

M. Friend, W. D. (2013, 11 17). The Special Education Referral, Assessment, Eligibility, Planning, and Placement Process. Retrieved from Education.com: www.education.com/print/special-education-referral-assessment/

Major, A. E. (2012). Job Design for Special Edcuation Teachers. Current issues in Education Volume 15.

Martinez, A. M. (2011). Explicit and differentiated phonics instruction as a tool to improve literacy skills for children learning English as a foreign language. GIST Education and Learning Research Journal, 25-49.

Maxwell, J. C. (2011). The 5 Levels of Leadership. New York: Center Street Hatchette Book Group.

Miller, L. C. (2007). A randomized controlled pilot study of the effectiveness of occupational therapy for children with sensory modulation disorder. . American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 228-238. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.228

Morewood , A., & Condo, A. (2012). A Preservice Special Education Teacher’s. American Council in Rural Special Educatian.

Muffler, A. (2014, October 2014). Interview with Andrew Muffler. (A. Ivie, Interviewer)

NICHCY. (2012, 03). Categories of Disability Under IDEA. Retrieved from National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities: nichcy.org/wp-content/uploads/docs/gr3.pdf

Pardini, P. (2013, 11). The History of Special Education. Retrieved from rethinging schools. org: www.rethirngingschools.org/restrict.asp?path=archive/16_03/Hist163.shtml

Parent Brief Promoting Effective Parent Involvement in Secondary Educaiton. (2002, July). Retrieved from National Center on Secondary Education and Transition: ncset.org/premium-publications/printresource.asp?=423

Parsons, S. (2012). Adaptive teaching in literacy instruction: case studies of two teachers. Journal of Literacy Research, 44, 149-170.

Patrick, D. (2014, October 30). SB 1380 House Committee Report Version. Retrieved from Texas Legislature Online: www.capitol.state.tx.us/Search/DocViewer.aspx

Phipps v Clark County School District, 2:13-cv-00002 (United States District Court for the District of Nevada January 25, 2013).

Plock v Board of Education of Freeport School District , 07 c 50060 (United States District Court, N.D. Illinois, Western Division December 18, 2007).

Prater, M. A., Dyches, T. T., & Johnstun, M. (2006). Teaching students about learning disabilities through children’s literature. Intervention in School and Clinic, 42(1), 14-24.

Rambin, J. (2014, October 30). Bill Requiring Surveillance In Special Education Classes Heads to House. Retrieved from Austinist: austinist.com/2013/04/08/bill_requiring_surveillance_in_spec.php

Rehabilitation, V. (2013). Vocational Rehabilitation Services for High School Students with Disabilities. Retrieved from Executive Office of Health and Human Services: www.mass.gov/eohhs/consumer/family-services/youth-services/youth-with-disabilities/vocational-services.html

Reis, S. M., McCoach, D. B., Little, C. A., Muller, L. M., & Kaniskan, R. B. (2011). The effects of Differentiated Instruction. American Educational Research Journal, 462-501.

Rubin, C. M. (2013, Jan 14). The Global Search for Education: What Will Finland Do Next? Retrieved from Huff Post Education: www.huffingtonpost.com/c-m-rubin/finland-education_b_2468823.html

Sahlberg, P. (2012). A Model Lesson; Finland Shows Us What Equal Opportunity Looks Like. American Educator, 20-40.

Salem, L. C. (2006). Children’s literature studies: Cases and discussions. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Saunders, A. F., Spooner, F., Browder, D., Wakeman, S., & Lee, A. (2013). Teaching Common Core in English Language Arts to Students with Severe Disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Students , 46(2), 22-33.

Saundres, A. F., Bethune, K. S., Spooner, F., & Browder, D. (2013). Solving the Common Core Equation Teaching Mathematics CCSS to students with moderate and severe disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 45(3), 24-33.

Servillo, K. L. (2009). You get to choose! Motivating students to read through differentiated instruction. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 2-11.

Short, K., Evans, A., & Hildebrand, K. (2011, August/September). Celebrating International Books in Today’s Classroom: The Notable Books for a Global Society Award. Reading Today, pp. 34-36.

Springer, B. (2014, October 31). Inteview with Ben Springer. (A. Ivie, Interviewer)

Stanford, B., & Reeves, S. (2009). Making it happen: Using differentiated instruction, retrofit framework. and Universal Design for Learning. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 1-9.

Stanford, P., Crowe, M. W., & Flice, H. (2010). Differentiating with technology. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 2-9.

Subban, P. (2006). Differentiated instruction: A research basis. International Education Journal, 935-947.

Subban, P. (2006). Differentiated Instruction: A research basis. International Education Journal, 7(7), 935-947. Retrieved 12 02, 2016, from files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ854351.pdf

Sullivan, K. (2011, October 27). Book Award Celebrates Awareness for Disabilities. Inside Eau Claire.

The Council of Chief State School Officers. (2014, October 30). Educational Leadership Policy Standards. Retrieved from ISSLC 2008: www.vide.vi/data/userfiles/Educational_Leadership_Policy_Standards_2008%20(1)(1).pdf

Thomas E. Scruggs, F. J. (2013). Common Core Science Standards: Implications for Students with Learning Disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 49-57.

Thompson, C. (2011). Multi-Sensory Intervention Observational Research. International Journal of Special Education, 26(1), 202-214. Retrieved November 5, 2016, from eric.ed.gov

Tomchek, S. D. (2007, March/April). Sensory Processing in Children With and Without Autism: A Comparative Study Using the Short Sensory Profile. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(2), 190-200. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.190

Tomlinson, C. (2009, July 24). What is differentiated instruction? Retrieved from Reading Rockets: www.readingrockets.org/article/what-differentiated-instruction

Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). Mapping a route toward differentiated instruction. Educational Leadership, 57(1), 12-16. Retrieved 12 03, 2016, from blog.elanco.org/gsgsteacherresources/files/2015/01/Mapping-a-Route-Towards-Differentiated-Instruction-1synvr0.pdf

University of Michigan: SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION . (2013). Retrieved from Unversity of Michigan; Department of Psychology: sitemaker.umich.edu/delicata.356/funding_for_special_needs_education

Utah State Office of Education. (2014, October 31). LRBI Guidelines. Retrieved from Utah State Office of Education: www.schools.utah.gov/sars/DOCS/resources/lrbi07-09.aspx

Vaughn, S., & Linan-Thompson, S. (2003, Fall). What is special about special education for students with learning disabilities? The Journal of Special Education, 37(3), 140-147. Retrieved 12 02, 2016, from files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ785943.pdf

Villeneuve, M. &. (2012). Enabling Outcomes for Students with Developmental Disabilities through Collaborative Consultation. The Qualitative Report, 17, 1-29. Retrieved November 5, 2016, from www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR17/villeneuve.pdf

Wasburn, M., Wasburn-Moses, L., & Davis , D. R. (2012). Mentoring Special Educators:. Hammill Institute on Disabilities, 59-66.

Washburn-Moses, L. (2005, January). How to Keep Your Special Education Teachers. Retrieved from Managing Your School: www.nassp.org/portals/0/content/49169.pdf

Winzer, M. A. (2006). Confronting difference: an exursion through the history of special education. In M. a. Winzer, The SAGE Handbook of Special Educaiton. SAGE Publications.

About the Author

Louris Otero has been teaching first grade for 14 years at Carrollton School of the Sacred Heart in Miami, Florida. She is currently pursuing her MS in Special Education with an endorsement in Autism from Florida International University. Ms. Otero has been happily married for 20 years and is the mother of two teenagers, Serena, 18 and Justin, 16. This is her third publication.

Appendix A

Student Surveys

Student Self-Assessment

Circle the best answer.

I am a good listener. Always Sometimes Never

I follow instructions. Always Sometimes Never

I stay in my seat. Always Sometimes Never

Student Exit Survey

Name ________________________________________________________________________

I am a BETTER WORSE listener with a fidget toy.

Student Self-Assessment

The toy helped me stay in my seat. Always Sometimes Never

The toy helped me listen to my teacher. Always Sometimes Never

The toy helped me complete my work. Always Sometimes Never

Appendix B

Administrative consent for action research

By Maria Ibarra

Kotter, P. John. A Force for Change: How Leadership Differs from Management. New York: The Free Press, 1990. 177 pp. $ 17.00.

Introduction

Dr. John Paul Kotter has been recognized as a well-known expert on leadership. He is a professor of Organizational Behavior at Harvard Business School in Cambridge, MA. He has conducted intensive research in organizational change and he is the author of twenty successful books. Twelve of his books have been business bestsellers and two overall New York Times bestsellers.

Purpose and Thesis

John Kotter wrote “A Force for Change” in response to the growing debate regarding what constitutes good leadership. This author states that “leadership in complex organizations is an increasingly important yet often confused topic which can be further illuminated by exploring its relationship to management, a very different sort of activity and one that is much better understood today” (viii). The author further argues that many people have the wrong “notion that leadership is good and management is bad” and that “many firms today lack sufficient leadership, a deficiency that is increasingly costly, yet often correctable” (ix). The purpose of this book is to shed some light on the confusing concepts of leadership and management within complex organizations. The author provides a framework to guide administrators to effectively lead and manage their organizations.

The author’s thesis is that effective leadership and competent management are two important processes needed for organizations to experience success and prosperity. The author argues that the primary function of effective leadership is to create “constructive or adaptive change” (5) whereas the primary function of management is enabling the organization to be kept “in order; on time and on budget.” Furthermore, effective leadership produces movement while management produces consistency (4). The author thoroughly explains that “leadership produces useful change and management creates orderly outcomes which keep organizations in working efficiently” (7). In addition, the author also advises leaders that when leadership and management are used in conjunction, “an effective leadership can produce the changes necessary to bring a chaotic situations under control” (7).

Strength and Challenges

Kotter offers an in-depth analysis of what constitutes the leadership process as he provides a mere explanation of processes, function, and structure of what constitutes good leadership. He makes the critical distinction between leadership and management, and he recognizes the importance of both processes. The author argues that essential features that both processes share are: establishing goals, creating networks of people and relationship that enable all individuals to accomplish their goals; and ensuring that goals are accomplished (5). In a similar vein, Fullan (2001) supports the importance for leaders in being relationship builders with diverse groups and further emphasizes the importance in fostering interactions that promotes sharing expertise.

Kotter clearly describes three essential sub-processes that help administrators to successfully lead: establishing directions, aligning people, and motivating and inspiring. On the other hand, management is achieved through three processes: planning and budgeting, organizing and staffing, and controlling as well as problem solving. Kotter highlights a key difference between the two processes. He states that an important outcome obtained from engaging in good management is consistency and order.

However, leadership differs from management in that it produces movement and change rather than consistency (4). Fullan’s framework of leadership also supports the importance of understanding change in successful leadership. According to Fullan (2001), change creates disequilibrium, which could be uncomfortable, but if relationships are good prior to the changes, they become better during the process. Thus, it is important for people to make sense of the process of change.

One strength of this book is that the author provides great examples of effective leadership and clearly illustrates the function of leadership to produce useful and significant change. The examples throughout the book also illustrates how effective leadership combined with competent management can lead to great business success. Another important strength of the book is that if offers comprehensive postscripts that enable readers to understand key ideas discussed throughout the book, such as postscripts include: comparing management and leadership, the relationship of change and complexity to the amount of leadership and management needed in a firm, consequences of strong leadership and weak management in a complex organization, the interrelation of direction setting and planning in a complex organization, aligning people, motivating and inspiring, developing a human system/network for achieving an agenda, and management and leadership roles.

Kotter helpfully provides a framework to guide leaders to effective lead their organization as he successfully help readers understand what leadership is, why this process is important, and how leadership differs from management. Kotter argues that “organizations that are both, well-led and well-managed” have a clear sense of direction and relevant planning activities, “but they are in the minority today” (39). Kotter clearly explains that establishing direction is a core aspect of leadership because “it creates vision and strategies” (36), but he also acknowledges the importance of planning in management today as it creates consistency and predictability (38).

Kotter clearly explains the important role that vision plays as it provides guidance to people in what a company should achieve or accomplish. He states that “vision is a description of an organization, a corporate culture, a business, a technology, or an activity in the future in terms of the essence of what it should become” (36). The positive impact of vision in leading is also supported by Fullan (2001) framework of leadership. Fullan argues that vision can attract the commitment and energies of employees, but only when shared with all individuals in an organization.

The author provides a thorough explanation regarding the importance of direction and planning. These points were clearly articulated by arguing that vision and strategies involve taking risks, which are essential in order to make change happen. However, the planning process of management helps people accomplish goals in a consistent and predictable manner. The author also argued that “strong leadership can disrupt an orderly planning system and strong management can discourage the risk taking and enthusiasm needed for leadership” (7). These points are very relevant to help readers distinguish between direction as well as planning setting. The author emphasizes that it is critical to understand the difference between both and failure to recognize such a distinction results in “over-managed and under-led organizations” supporting “long-term planning” and lacking “direction.” Consequently, these organizations fail “to adapt to increasingly competitive and dynamic business environments” (37).

One challenge that the author has is explaining the rationale underlying the practice of aligning, motivating, and inspiring in successful leadership as he overlooks the role of emotion in relationships. The author identifies aligning as a process that involves having people lined up behind a vision and enabling them to use strategies that result in change. He argues that a key aspect of aligning is communication. The author also warns us against the challenge of getting people to understand a vision and complying to make the direction a reality which consequently leads to making progress towards a target. The author further argues that motivation and inspiration involves energizing people to overcome obstacles they find as they try to achieve a vision. He also argues that successful leaders help people to be motivated for long periods of time. However, Fullan (2001) takes these ideas further by arguing that in a culture of change, emotion may have an impact on people’s opinion which leads to reservations and opposition to new directions. In addition, leaders must appreciate resistance and help people work together in the change process. I tend to agree with Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) viewpoint about the role of emotions. They argue that individuals’ emotions and feelings have to be shared in order to build mutual trust among individuals with different perspectives and motivations.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The book is clear, readable and amply illustrated with sufficient examples. This book offers a great guide for administrators who need to lead and manage in their organization as they need to create a changing culture as well as consistency and predictability. The author encourages leaders to lead and manage to successfully create productive and meaningful change. A book on this topic is important to administrators in business and schools because it helps them to distinguish between what constitutes a good leadership versus good management in order to successfully create the culture that is needed to help others to lead. The topic of this book is also relevant to leaders who work in complex organizations such as businesses or schools that experience constant change. A Force for Change is an enjoyable and interesting book that offers excellent strategies to effectively lead and manage and it offers an outstanding resource for administrators.

References

Fullan, M. (2001). Leading in a Culture of Change. San Francisco, CA. A

Wiley Imprint.

Kotter, P. John. (1990). A force for Change: How leadership differs from management. New

York: The Free Press.

Nonaka, L., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-creating company. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

About the Author

Maria Ibarra is from Guayaquil, Ecuador. She is currently working as a middle school teacher in Broward County, Florida. Ms. Ibarra has a passion for working with 7th and 8th grade students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. She has her Bachelor’s in Psychology from Florida Atlantic University and her Masters in Special Education with an endorsement in Autism Spectrum Disorder from Florida International University. Ms. Ibarra is married and is the mother of an eight year old.

By Joyce Pickering, MA, SLP/CCC, HumD

Abstract

In this article, Dr. Joyce Pickering—a Montessori educator, speech and hearing pathologist, and learning-differences special—explores why the Montessori Method, with its comprehensive multisensory curriculum, is critical to the progress of children who learn differently—including children with dyslexia, ADHD, communication disorders, intellectual deficiencies, and autism. Pickering provides a comprehensive and detailed suite of therapeutic strategies that can be used with this population, along with the Montessori Method, to enhance students’ educational progress. The immediate past president of the American Montessori Society, Pickering is also executive director emerita of Shelton School & Evaluation Center in Dallas, Texas, the world’s largest private school for children with learning differences.

In 1950, Dr. Maria Montessori gave a lecture at the University for Foreigners, in Perugia, Italy, in which she drew a diagram of the four planes of development (Grazzini, 1988). The triangles represent Montessori’s fundamental psychological theory, with each plane representing one of the sensitive periods of development.

“Montessori education is geared to peaks and valleys of human formation.” Dr. Montessori suggested we “divide education into planes and each of these should correspond to the phase the developing individual goes through”.

This diagram represents the progression of typical development from birth to age 24. Montessori, who had worked with children with varying exceptionalities, at the Orthophrenic School, in Rome, recognized that children challenged in learning had what she referred to as an unequal development. As we look at the four planes for the typical child, we might envision all of the lines from birth to age 24 as wavy lines, indicating this unequal development.

The development of the “at risk” child is uneven. Some areas are developing typically; others are not. The sensitive periods are different. Since the development in the first 6 years is different, all other periods of development are affected.

In a 1988 lecture, Dr. Sylvia Richardson suggested that to identify children at risk for learning differences with the goal of early intervention, the teacher should observe the development of coordination, language, attention, and perception. All of these areas can be clearly observed in the Montessori classroom. In particular, the Sensorial curriculum helps the teacher to observe the child’s perceptual development and is diagnostic of uneven development.

In The Absorbent Mind, Montessori (1967) also described the early development of children between birth and 3 years of age as proceeding along different tracks. For example, coordination might be developing typically, while language and speech may show delays of disorder and attention and perception may be below average for typical development. There could be any combination of these unequally developing areas. It is important that these areas, which will contribute to cognitive ability and adaptive ability, develop evenly, because in the period between 3 and 6 years, Montessori indicates these important skills will be integrated, and if there is uneven development, it hinders the integration of these skills to assist the child in learning. This creates a domino effect, in which unequal early development and integration of these skills affect all of the planes that follow the first, hence contributing to learning differences.

Working from this premise, Montessori (along with French physicians Jean Marc Gaspard ltard and Edouard Seguin) explored ways that education could help minimize the differences between the typically developing child and the child who experiences learning and attention differences. This early work in sensory education led to the comprehensive multisensory curriculum of the Montessori Method. While the Method helps all children, it is critical to the progress of children who learn differently—including children with dyslexia, ADHD, communication disorders, intellectual deficiencies, and autism. I will briefly describe these learning differences and then discuss how the Montessori curriculum can be used with children with these differences.

The research of Dr. Gordon Sherman, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, in Boston, has shown that the child with the specific reading disorder of dyslexia has a brain that is significantly different from the typical reader—not damaged or abnormal, just different (Sherman & Cowen, 2003). Using MRI studies of individuals with dyslexia reading, Dr. Sally Shaywitz, of the Yale University School of Medicine (2003), has found that the dyslexic brain is processing letters and sounds into words as the beginning reader does rather than as the typical reader, who, becoming fluent, primarily uses the word form area of the brain. Even in adulthood, the individual with dyslexia does not process visual and auditory information as the typical reader does.

Studies of ADHD indicate that this difference is a chronic neurobiological condition in which the person has difficulty with sustained attention and impulse control. Persons with ADHD have a physical, neurological challenge caused by a lack of release of neurotransmitters in the brain that assist with arousal and ability to concentrate and control impulses. Difficulty with executive function is noted in children with ADHD—they have trouble organizing and prioritizing.

For children with communication disorders, including speech and language development difficulties, we see differences in articulation, fluency of speech, language comprehension, and expression. The brain is not processing auditory information accurately or performing the task of bringing meaning to the words that are heard.

Students on the autism spectrum have challenges with oral language development and social skill development. Children with intellectual deficiency have low average mental ability to severe deficiency in intellectual development.

Each of the difficulties listed above can be found individually or in combination, preventing a student from learning as a typically developing student does.

To help the child who learns differently, when the usual presentation is not helping a student, Montessori educators can use several techniques:

- reduce the difficulty of an activity

- use more tactile-kinesthetic input

- create control charts

- focus on the development of oral language

- increase the structure for the child with impulse control difficulties, assuming the necessity to help the ADHD child to sustain attention, teaching how to make work choices and how to develop a cycle of work

- combine Multisensory Structured Language techniques with Montessori Language presentations.

Examples of these techniques are given below.

PRACTICAL LIFE:

- Use fewer dry materials in initial pouring activities (for example, 5 large beans versus many grains of rice) and less liquid.

- Note: If the child is not holding the pitcher correctly, the lesson may have to become how to hold a pitcher and work up to pouring.

- Dressing Frames: lesson reduced to a first presentation of untying, unbuttoning, unbuckling, etc., with each step presented in separate lessons working toward the final step of mastering the direct purpose of the lesson

- Cutting bananas and bread before cutting more solid foods, like carrots

- Attaching language to the name of the presentation and all of the materials used in the lesson that is at the level of the child’s oral language development

SENSORIAL:

- Pink Tower: Reduce the number of cubes to use every other cube, beginning with the largest, thereby increasing the discrimination to a 2 cm difference. Use more tactile kinesthetic exploration of each cube, if necessary, to show the child how to make the choice; arrange the cubes in random order on the mat and say “find the big one.” Repeat this for the first 3 cubes. After the third cube, most children perceive how the choice is being made to build the cubes in gradation. This activity varies in 3 dimensions—height, width, and depth.

- Brown Prisms (Brown Stairs): Use the same procedures as described for the Pink Tower. This activity varies in 2 dimensions—height and width.

- Red Rods: Use the same procedures as described for the Pink Tower. It may be necessary to create a control chart for the child to practice building the rods from long to short, until he perceives the difference, which in this activity varies only by one dimension—length.

- Knobless Cylinders: Use the same procedures as described for the Pink Tower.

- Geometric Solids and Geometric Cabinet: Demonstrate to the child as you present the use of the senses of feel (tactile and kinesthetic), which will assist visual perception.

- Color Box III: Reduce the number of shades to be discriminated between, beginning with 3 dark, 3 lighter, and 3 lightest. Increase the range of discrimination until the child can perceive the differences in all 7 shades. A control chart can also be used.

- Memory Bag: Begin the year with objects in the bag that are made of different materials and are distinctly different in shape. During the year, increase the difficulty by making all of the objects of the same material, such as wood, and increase the similarity of the shapes of the objects. With all Sensorial activities, add as much language to the presentation as possible (after the initial silent presentation). Naming each object (e.g., big, little; large, small; larger, smaller; largest, smallest) expands the child’s vocabulary. As the child is able, add describing words to each activity (e.g., heavy, light, rough, smooth, and the names of colors).

MATHEMATICS:

- As with the Sensorial materials, add the sense of feel, both tactile and kinesthetic, to the presentation of each Math material. This assists the child whose visual al perception is faulty.

- Number Rods: As language is attached after the initial presentation, each rod should be touched and counted. For example, perceptually the 2 rod is not actually two things, but one rod painted in two different colors to represent the quantity 2. If, during the presentation, the teacher says, “This is 2,” and touches and counts, “1, 2,” the child ‘s perception may be more accurate. This is true for all rods from 2 to 10.

- Spindle Box: When presenting, tap the rod into the palm of the other hand. This increases the sense of feel and assists the child when he imitates this movement in one-to-one correspondence in counting. If the child or other children in the room are sensitive to the sound of the rods dropping into the box, line the number slots with felt.

- Cards and Counters: If the child shows confusion with all 10 numerals and counters, reduce the number to S and build up to 10 as the child indicates he can accomplish the work. Use this activity in the Elementary program, and expand it to the realization that all numbers that end in 2 are even, including 12, 22, 102, 1002, etc.

- For math functions (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division), children with learning differences usually need more repetition. It is very import ant to attach language to each math function: Adding is putting amounts together, subtraction is taking an amount from a larger amount, multiplication is a fast way of adding, and division is a way to allot equal amounts to each person. All of these words are abstract and the Montessori Math materials provide ways to help make them more concrete and hence more understandable.

- Typically developing students seem to pick up math facts by using the Golden Beads for the math functions, along with the addition and subtraction strip boards. Those with visual and auditory processing difficulty have more challenges in learning these facts. In addition to manipulatives, practice writing number facts on a textured surface, thus using four VAKT channels (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile) to help the student store information in memory. Various VAKT strategies include writing on the textured side of an 8″ x 11″ piece of Masonite board, writing in a sand tray, writing on a flat surface covered with shaving cream, and skywriting. Skywriting entails using the nondominant hand placed on the shoulder of the dominant hand while the student traces the letter or word in the air with a large arm movement.

- Making transitions from the Golden Beads to a more abstract work, like the Small Bead Frame, in which color represents quantity, usually takes more time and practice.

LANGUAGE:

- Since oral language skills may be a weakness for many students with learning differences, it is usually necessary to add a program of oral language development assessment and instruction to enhance vocabulary and verbal expression. The MACAR Oral Language Development Manual is one such program (Pickering, 1976).

- Written language, which includes reading, spelling, composition, and handwriting, requires the combination of Montessori language materials and the therapeutic techniques of a multisensory structured language (MSL) approach (e.g., Orton-Gillingham, Sequential English Education (SEE), Slingerland, Spalding, or Wilson Language).

- Use additional phonological awareness shelf activities (pat out each sound in a word; place a small floral stone or disk on a picture card for each sound in a word).

- Present the Sandpaper Letters in the sequence taught in the therapeutic program.

- Use the decoding pattern of blending the beginning sound to the word family of short and long vowel word family words. In this manner of decoding, the student is blending two units of sound rather than three or more, which is more difficult.

- Reduce the difficulty of word building by reducing the number of letters used and not presenting the full tray, which can be overwhelming to students with processing difficulties. For example, use a set of S pictures (cat, hat, sat, mat, bat) and just the letters needed to build the words (5 As, 5 Ts, and one each of C, H, S, M, and B). Students with processing challenges have difficulty seeing the patterns in words. These sets are put together by word family, such as at, ap, ab, an, ag, etc. The same types of sets are made for the other short vowel word families. After mastery of the short vowel patterns, long vowel word families may be used in a similar fashion.

- Montessori’s excellent sequence of language materials are multisensory and sequential. The MSL pro gram adds more detail to the strategies that work for students who learn typically in order to adapt them for those who learn differently. As the student proceeds to more irregularities of language, Montessori color-coded works provide for these higher-level language skills to increase accurate reading and spelling. Comprehension is embedded in the early word building by attaching meaning through the use of pictures for each word that is built.

- Use linguistic readers to practice the patterns the student is learning. Decoding and comprehension are included in these readers and subsequent readers as they master more patterns of the language. Handwriting is carefully taught by beginning with prewriting activities, including the Metal Insets. The formation of each letter is taught, preferably in cursive, beginning with the Sandpaper Letters. Students with learning differences experience spatial and directionality confusions. Cursive with letters connected into words and spaces between the words is an assist to these students. There are fewer reversals noted in cursive and the writing is more legible. There is no difference in the motoric requirements for one handwriting system over another. Students learning to write in cursive do not have a problem reading print.

- Montessori grammar is very helpful for all children, including those with learning differences. The gram mar symbols help make a very abstract concept parts of speech- more concrete. Grammar boxes and sentence analysis are organized in a way for the student to understand the structure of the language.

For students of all ages—Early Childhood through college—the strategies described here can be applied to the level of the concepts being taught. Developmental stage, rather than chronological age, is the critical factor in helping a child learn. The art of teaching is to match the level of the lesson to the student’s individual developmental stage using the Montessori Method and therapeutic strategies, as necessary, to enhance the educational progress of the student.

References

Grazzini, C. (Jan.-Feb.1988). The four planes of development: A constructive rhythm of life. Montessori Today. 1(1), 7-8.

Montessori, M. (1967). The absorbent mind. New York: Dell Publishing Co., p. 6.

Pickering, J.S. (1976). Montessori applied to children at risk oral language development curriculum. Saõ Paulo, Brazil: Escola Graduada de Saõ Paulo, p. 8.

Richardson, S. (1988). Lecture given to the Florida branch of the International Dyslexia Society.

Shaywitz, S. (2003). Overcoming dyslexia: A new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, p. 9.

Sherman, G. & Cowen, C. D. (2003, spring). Neuroanatomy of dyslexia through the lens of cerebrodiversity. Perspectives, 29(2), 9-13. Baltimore, MD: International Dyslexia

About the Author

JOYCE PICKERING MA, SLP/CCC, HUMD, is a speech and hearing pathologist, and learning disabilities specialist who has devoted her life to addressing the needs of students with learning differences. She is also a Montessori-credentialed educator with more than four decades of experience in the field. Currently Dr. Pickering is executive director emerita at Shelton School & Evaluation Center, in Dallas, Texas, the world’s largest private school for children with learning differences. She is also the immediate past president of the Board of Directors of the American Montessori Society, a professional membership organization with 15,000 members worldwide.

© American Montessori Society 2017. Originally published in Montessori Life, Vol. 29, No. 1, Spring 2017. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

By Norma Samburgo

Whitaker, T. (2013). What Great Principals Do Differently: 18 Things That Matter the Most. New York: Routledge. 146 pp. $39.90.

“Great principals never forget that is people, not programs, who determine the quality of a school” declares the author of this book while explaining the qualities that distinguish great school leaders. Todd Whitaker started his career as math teacher in Missouri and years later became a principal serving middle school, junior high, and high schools levels. Currently, Whitaker is professor of educational leadership at Indiana State University. His passion for education motivated him to research and study effective teachers and principals which made the basis for writing more than forty publications about staff motivation, teacher leadership, and principal effectiveness.

Dr. Whitaker wrote this book with the purpose of spreading the idea that, even though school leadership is extremely complex, there is a way to refine principal’ skills and continuously work to be better. We can accomplish that by analyzing what great principals do, what distinguish them from others, how they reach success under their practice, and how we can implement what principals do best every day. All schools leaders should adopt the best practices used by their most effective colleagues. As stated by the author: “…if all schools had leaders like the best principals, the students who walk through their doors each day would face every school year with confidence” (3).

What Great Principals Do Differently consists of twenty chapters where characteristics of great school leaders are identified and developed. Whitaker talks about classroom management and how effective leaders promote individual teacher development to strengthen their skills, how they visit classrooms as a way to share problem solving decisions, and how they have to take responsibility for everything that happens in the school. From topics about respect and loyalty to teacher hiring process and dynamics of change, the author analyzes and transmits the best recommendations to be use for school leaders who want to succeed under their practice. In the last chapter, he resumes the book by asserting: “…The principals are the architects. The teachers establish the foundation. The students move into the building and fill it with life and meaning” (141).

The author uses three different perspectives to support his arguments and to demonstrate why every school leader should adopt the best practices of their colleagues’ accomplishments. First, he uses the research studies he participated in during visits to school. Second, his experience as school consultant where he had the opportunity to observe principals, teachers, students, and staff and expanded his understanding of what conducts to achievement. The third perspective was his personal experience as school principal.