Table of Contents

-

The Parent Connection: Creating a Partnership Between Home and School: A Review of the Literature. By Candy Allen

-

Positive Behavior Intervention to Improve Study Skills. By Janine Castro

-

Using Augmentative Communication to Teach Non-Verbal ASD Students to Communicate. By Chelsie Madiedo

-

Parental Satisfaction: Issues with Special Education and Possible Solutions. By Louris Otero

-

Parent Advocacy and Involvement for Children with Disabilities. By Ashley Randall

-

Effectively Preparing Educators and Staff to Empower Diverse Students Within an Inclusive Classroom Setting. By Mary Samour

-

Special Education Legal Alert. By Perry A. Zirkel

-

Buzz from the Hub

-

Latest Employment Opportunities Posted on NASET

-

Acknowledgements

-

Download a PDF or XPS Version of This Issue

By Candy Allen

The relationship between school and home is often an awkward one. Parents are misjudged, teachers are misunderstood, and expectations at both ends are different. Throw in the challenges of special education, add a dose of miscommunication, and you have a recipe for a challenging school year! What can be done to prevent this and create a successful, working partnership between home and school? This paper explores five published articles that address different aspects of the parent perspective and involvement with hopes of shedding light on this essential piece to building a successful, collaborative relationship between home and school.

Reasons for Parent Dissatisfaction

There are many reasons why parents become dissatisfied with the educational system. Parents are found to be dissatisfied when teachers and school personnel have a limited understanding of their child’s disability and the challenges that they face. Starr & Foy (2012) state that a “lack of teacher knowledge about the nature of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and effective interventions have been found to be major contributors to parent dissatisfaction” (p. 208). According to Starr & Foy, parents feel that teachers lack professional development training on ASD and behavior management techniques. As the numbers of students identified with ASD grows, so will the need for training that is based on the newest research.

Another contributing factor to parent dissatisfaction is the belief that there is ineffective communication and collaboration between the home and school. Valle (2011) discusses how in the past parents have been considered “passive recipients” of their child’s educational information instead of a “contributing” member of the team (p. 186). Parents have also felt left out of the process because of special education terminology and the “incomprehensible jargon” that is used at meetings (p.186). This is a common problem with parents and unless they are truly knowledgeable of the special education language they are left feeling like they are not an active participant in the process.

According to the study by Mandic, Rudd, Hehir and Acevedo-Garcia (2012), parent understanding of the Procedural Safeguards is limited. The Procedural Safeguards, part of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004, are in place to ensure that parents have a right to be a part of any decisions regarding the education of their child. However, the readability of the written language in this lengthy document is at “excessively high levels” (p.200). Many parents are not able to comprehend this written material. This study suggests that parents may not be aware of their rights and choices they have if they are dissatisfied. This can also add to the disconnect between home and school.

Parents of children with disabilities face many challenges in their daily lives. Brown, Ouellette-Kuntz, Hunter, Kelley, Cobigo and Lam (2010) studied how the child’s functioning level impacts a parent’s perception of unmet needs, showing that children with ASD with both lower and higher functioning levels left parents with higher levels of unmet needs. Children with ASD with lower functioning levels are much more challenging because of their intense behavior needs which creates greater stresses on the family. These behavior challenges also affect the school environment causing stress and lack of understanding between the home and school. Children with higher functioning levels also leave parents with unmet needs because these children are more independent and may not be “receiving the support necessary to fully participate with typical peers in educational, social and other activities.” (p.1302). This also affects the parent’s perspective on how the school system is supporting their child.

Starr and Foy (2012) found in their research that a teacher’s inability to manage student behavior led to increased dissatisfaction. Their findings also suggest that students with ASD may be suspended from school for behavioral issues at a higher rate than for students without disabilities. This points to the need for better awareness and understanding of ASD and behavioral strategies that should be used with these students.

Reasons for Parent Satisfaction

In the study by Starr & Foy (2012), teacher awareness and understanding of disabilities had a positive impact on a family’s perception. Parents need to know that their child’s teachers understand the many dynamics of disabilities and how it directly affects their child. Teachers need to continually learn about disabilities and improve their use of strategies and techniques to work with their student’s unique needs. Paraprofessionals working with students with disabilities also need updated training to assist them in their daily work in the classroom. Asperger syndrome can be difficult to visually see in a student because they look very typical. Parents felt that when staff were aware of the diagnosis of Asperger’s, they were more tolerant and helpful in creating a successful learning environment for their child (Starr & Foy, 2012). Regardless of the disability, there needs to be an appreciation of the challenges that families face and how teachers can assist.

When parents feel that there is effective communication and collaboration between the home and school, then parent satisfaction is improved. In research by Burke (2013) there is a direct correlation between family involvement and the success of students in school. Her findings suggest that training special education advocates to assist parents in their understanding of their rights, the terminology and ability to advocate for the student improves the success of the student and the collaborative environment between home and school.

How to Improve the Home/School Relationship

The literature suggests many strategies that can improve the home/school relationship. School staff needs to be conscientious of the use of special education “jargon” and be mindful that the parents might not be understanding the terminology (Valle, 2011). ESE Specialists should take the time to explain the Procedural Safeguards to the parents. Helping parents to understand this process will help them feel like everyone is on the same team for their child. Teachers and administrators need to encourage parent participation in the development of their child’s IEP and recognize that parents are the best source of information. In her research, Burke states that when there is “significant parental involvement” in the IEP process the home/school relationship is improved and the child is “more likely to receive a free, appropriate public education (FAPE)” (p. 226).

Parents are their child’s first teacher and have valuable input into effective strategies to use. Parents appreciate when teachers are interested and responsive to their perspective. This builds collaboration between home and school, and benefits the student because teachers are receptive to parent input regarding their child’s abilities (Starr & Foy, 2012).

Teachers need to be more sensitive to the challenges that parents have faced with their child through the years. Their child’s disability impacts much of their daily home life and whether it is functional levels, or the behavior needs of a child with ASD, the parents are struggling to make it all work. Teachers should not assume that behavior difficulties are all “discipline related” (Starr & Foy, 2012) and that upon analysis the behaviors can be attributed to a dynamic related to the child’s autism. Proper training in behavior management techniques is important for both teachers and paraprofessionals and gaining a better understanding in this area will help lead to parent satisfaction.

One important factor in successful parent/school relationships is having staff that are “caring and conscientious” (Starr & Foy, 2012). Understandably, parents are more comfortable with their child’s placement when they feel that the staff truly cares for their child. Trust and appreciation of each other’s role in the life of the child helps to build confidence and respect in the teacher and the school.

Conclusion

Although the articles reviewed were presented with different approaches, they all point to the need for improved collaboration and understanding between parents and school. When parents are feeling left out of the process, chances are other areas will begin to show signs of disconnect. There needs to be a comprehensive approach to improving parent involvement which should include (1) teacher professional development on disabilities and behavior management strategies to improve their professional practice, (2) promoting a caring and conscientious climate at the school, (3) a desire to understand and appreciate the parent perspective, and (4) taking time to ensure that parents understand the terminology used and their rights for their child. When parents are involved and feel that they are part of their child’s educational team both sides benefit and the child has the best opportunity for success.

References

Brown, H., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Hunter, D., Kelley, E., Cobigo, V., & Lam, M. (2011). Beyond an Autism Diagnosis: Children’s Functional Independence and Parents’ Unmet Needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1291-1302.

Burke, M. (2013). Improving Parental Involvement: Training Special Education Advocates. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23(4), 225-234.

Mandic, C. G., Rudd, R., Hehir, T., Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2012). Readability of Special Education Procedural Safeguards. The Journal of Special Education, (45)4, 195-203.

Starr, E., & Foy, J. (2012). In Parents’ Voices: The Education of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Remedial and Special Education,33(4), 207-216.

Valle, J. (2011). Down the Rabbit Hole: A Commentary About Research on Parents and Special Education.

By Janine Castro

Educators, and all school personnel, who are involved in a child’s education, have a common goal; which is to improve the academic and behavior performance of all students. There are plenty of new strategies, and approaches that teachers can use daily to help students who struggle with behavior and academics. Many of these approaches include positive behavior interventions to improve students’ study skills (McKevitt & Braaksma, 2008). Study skills are an important factor in students’ success, especially as these students’ progress from middle school to high school.

For some students who having behavioral and academic issues, academic success is impacted by their lack of basic academic skills (National Association of School Psychologist, 2002). Some students show behavior problems that may consume teachers and schools’ resources tremendously (Sugai & Horner, 2002). Students who are confident in their academic abilities are more likely to stay on task and less likely to engage in disruptive behaviors (Alderman, 2008). Basic academic skills can be strengthened by implementing interventions focused on improving study skills (Yaeger & Walton, 2011).

Positive behavior interventions in and out of the classroom environment may reduce the behavior problems and their consequences that vary from getting distracted and causing disruption in the classroom and being excluded from the instructional time. Educators understand that study skills are part of the learning process that it may take students with disabilities years to fully grasp the process. The use of positive interventions may improve study skills and make the learning process easier.

The purpose of this study was to explore the effect of positive behavior supports on the study skills of students identified as EBD, IND and SLD. Educators understand the need for positive behavior support that may provide students with an easier transition in the learning process and reduce negative behaviors that impede learning the necessary skills to use the instructional time in a better way, this study may help them to be successful in the classrooms.

This study was conducted in a Miami Dade County Public Schools high school setting

with special education students who were on a Special Diploma track and were using a modified

curriculum and accommodations as stated in their Individual Educational Plans (IEPs).

There were 15 total students in Grades 9-12 in the class and eight of them were chosen for the action research study. Their ages ranged from 14-22 years old. Most of the students’ disabilities were Intellectual Disabilities (IND), Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD), and Emotional or Behavioral Disabilities (EBD). Two students were also identified as having Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and one with Orthopedic Impediment (OI), and another one was English Language Learner (ELL).

In order to reinforce students’ positive behavior, the teacher implemented different reward activities like: breakfast at the school cafeteria, a board game day, a movie day, an extra credit day, which meant students who made an effort to behave well and finished their classwork, received their grade plus extra credit in their classes for that day. They also received stickers, certificates, positive notes to parents, and tokens.

The special education teacher was responsible for collecting the data. The school principal was informed about this study being conducted at the school site.

Review of the Literature

There are several studies which show positive behavior intervention being successfully used in the classroom to reinforce student performance in the classroom. Using these interventions, students may improve their study skills. One of the most important components of this strategy is focusing on the students’ positive aspects instead of the negative ones.

Teachers face many challenges, not only the responsibility they have as educators but the challenges of educating and managing students who have emotional and behavior disorders (EBD). According to the U.S. Department of Education, in 2012-2013, the U.S. served students ages 3 through 21; about 6% of those students were identified as EBD.

Positive Behavior Support: Strategies for Teachers

The use of positive behavior support (PBS) is a proactive approach to support and help students with challenging behavior. Before teachers initiate any PBS plan, there must be a collaborative team, a group of people who will support a student, gathering and evaluating information about the student’s behavior, the team needs to be sure that parents and teachers view a proposed plan as appropriate and reasonable. There are many people who handle discipline trying to eliminate challenging behavior without looking or finding why the behavior occurs, PBS is different, because is based in finding out not only what, where, when and how the challenging behavior happens but also why. PBS purpose is not to eliminate the behavior; rather it is to understand why the student is behaving this way and how to replace it with a new desired behavior that will accomplish the same goal. (Mayer & Sulzer-Azaroff, 1996; Walker, Colvin, & Ramsey, 1995) There are some aspects involved in the use of these interventions; the first one is identifying the purpose of challenging behavior, second is teaching students the appropriate responses and when this happens reward the positive behavior. (Durand & Crimmins, 1992) The main goal is to minimize any disruption caused in the learning environment that will avoid students develop the necessary study skills they need in order to succeed in the school setting.

PBS is focused on classroom management, and the use of any strategy teachers can apply in their classes to make it possible for children to behave and learn. One of the biggest author’s concerns is the teacher’s recognition that a child behavior is determined by the teacher behavior. The use of rewarding principles to get the desired students behavior in some cases will not give any solution to the problem, thus the behavior can be changed if first, teachers reward appropriate behavior and withdraw reward following inappropriate behavior. Second, if the first method is not successful, the rewards should be strengthening, and finally if method fails the inappropriate behavior should be punished while the appropriate one is being rewarding.

Peer Influence in Children and Adolescents

Research in this area, supports the theory that peer pressure and relationships influence the behavior in youth. Research has found the desired behavior may be offset by unexpected peer influence in different settings. Youth behavior becomes more deviant under unrestricted interaction with deviant peers, (Thornberry & Krohn, 1997). Deviant youth are placed in settings where they are in direct contact with other deviant youth, which increases the undesired behavior.

The vast amount of literature researching the role of unusual peer influence on inappropriate behavior in adolescent lends support to the hypothesis that trusting company with deviant peers considerably increases the probabilities of individual delinquency for at least some kinds of adolescents. Further research needs to be conducting in this area as there is a need to understand in which conditions this occurs, and in which conditions peer influence is mostly produced and the interventions that need to be used to specifically manage youth behavior in groups. There is plenty of questions that need to be answered and still too much to learn about how and why deviant peers contribute to the development of delinquency, empirical evidence based on random assignment studies suggests that such processes, could, in fact, occur (Dishion & Andrews, 1995; Feldman, 1992) A conscious examination of intervention programs may provide a particularly rich context for better understanding the function of these process and how to intervene to avoid them.

The Impact of Positive Behavior Intervention Training for Teachers

The impact of positive behavior intervention focuses in the relationship between behavior management and students’ achievement, and the importance of training teachers in positive behavior intervention techniques. The study was conducted in three K-8 schools with similar student populations and the three of them are characterized by low academic achievement, a high percentage of novice teachers and high teachers request for transfers or retirement

The relationship between behavior management and student achievement has been studied for a long time. Teachers’ education programs must recognize the importance of training new teachers in positive behavior intervention techniques. Novice teachers show lack of techniques to create an effective learning environment and maximize students’ performance, even though some teachers may have knowledge about what strategies to use they may not know how or when to implement them. The basic need of a beginner teacher is to understand that the deficit or excessive behavior interventions might stablish norms that can design the whole class and individual intervention will reinforce the desired behavior in the classroom improving students’ performance. Teacher organization which includes daily routines is also essential to promote discipline and encourage students to learn and function in school setting (Polloway, Patton & Serna, 2001). To give a solution to one of the biggest problem in the schools, disruption of instructional time due to behavior problems, all school staff and personnel who are involved in the children education was trained focusing on behavior management procedures and the use of positive behavior intervention. Plenty of techniques were taught in this program, such as: identifying classroom rules and procedures, reinforces, positive interventions, rewards, helping teachers to change their approaches. The program empowers teachers to create classroom with a safe, and friendly environment where children will feel secure and self-confident to challenge themselves and go over their hard academic assignments and change the inappropriate behavior. In a liable classroom teacher will use positive behavior interventions to maintain the learning process in a consistent manner.

As a result of professional development program, great changes in the three schools were noted, Data shows students behavior change dramatically; teachers treated children with boundless respect, faculty showed less stress, team work among teachers and paraprofessionals functioned in a more regularly and productive manner, sub teachers noticed the positive changes in students’ behavior, the whole school communicate, participate and interact in the program.

The findings in this program, which is the impact of positive behavior intervention, proved what teachers and researchers have mention about teaching in a classroom, that classroom management is a requisite to create successful students academically and the use of less time in correcting disruptive behavior will result in the use of more time for academic instruction, the findings in this study is supported in the literature: “Effective classroom management is required if students are to benefit from any form of instruction, especially in inclusive classrooms where students display a wide range of diversity [Jones & Jones, 2001)]” (Smith, Polloway, Patton & Dowdy, 2004, p. 42).

The use of this school-wide approach and the training of all the personnel have impacted in a great manner the school climate and improve students’ behavior, allowing teachers use their time to help students accomplish their goals and be successful.

Teachers’ referrals were basically due to poor academic performance, but half also include misbehavior as one main reason for referral. Teachers referring students having a disability and being eligible to receive special education services was about 90% (Gottlieb, Gottlieb & Trongone, 1991) Teachers referrals were not distributed evenly, as one eighth of the teachers made two-thirds of all referrals (Gottlieb & Weinberg, 2000). Principals and administrators’ motivation was if teachers were taught effective behavior management strategies, they would use them and eventually reduce the numbers of referral and there would be a tremendous reduction in the special education population in the schools.

Factors That May Improve Student Motivation

One of the key factors educators target as a very important one is motivation. During the

learning process, very few things can be done if students are not motivated; motivation occurs when these five ingredients are together: student, teacher, content, method/process, and environment (Olson, 1997; Williams & Williams, 2011). Several questions may appear when teaching is in process, which of these ingredients to use? When? How, what is the best strategy to motivate a student? The importance of choosing and trying not all, but the appropriate ones is based on teacher’s self-observation, educators could watch their behavior to understand and use motivation in a better way.

Some theories explain why people are motivated by reward, stimulus, influence, incentive, or just the desire that cause a person to act, desire to increase power, prestige, recognition, and the overheads or effort to achieve results (DuBrin, 2008)

A motivated student is easy to recognize as participates in the classroom activities, is engaged most of the time, answer questions promptly and seems to be happy in the classroom setting. The five key ingredients that impacts student’s motivation work together, are correlated and maximize students’ performance. Teachers must be prepared, knowledgeable, well trained, dedicated, and inspirational. The content must be accurate, and reach each one of the students’ needs in the present and future also. The process must be interesting, beneficial, encouraging, and provide students with the tools they need in real life. The environment needs to be as personalized as much as possible, to empower students in a positive way. To optimize motivation students must be exposed to motivating experiences and variable on a regular basis, which means students should have different sources of motivation in their daily learning process in the classroom (Palmer, 2007; Debnath, 2005; D’Souza & Maheshwari, 2010)

Literature about students’ motivation also mentioned, the more comfortable students feel in themselves and with their classmates, the easier is to concentrate and achieve their goals, this way emotional literacy has a positive impact on students’ achievement, behavior, and workplace efficiency. Teacher can create and model essential skills and learning behaviors including self-awareness, empathy, managing feelings, motivation, and social skills, which means instructors should stand firm, relate positively with students, and provide support, constantly self-improving and observing techniques that should not be only pedagogical but also on the social and emotional dynamics of the student-teacher relationship (MacGrath, 2005; Lammers & Smith, 2008; Wightin, Liu, and ROvai, 2008)

The studies discussed in this literature review support the use of positive behavior strategies for students who are identified as EBD, lack motivation, or present consistent behavioral problems that disrupt classroom instruction. All the strategies to motivate students must be used as often as possible, there is not a unique strategy to motivate and encourage students, and there is not a single and complete theory that explains it. New understanding, new ideas can be translated into the classroom, and as it was mention before the five key components must be functioning all the time during the teaching and learning process in order to motivate students. Another important aspect is educators must observe themselves and evaluate to promote motivation (Williams & Williams, 2011).

Action Plan (methods)

|

|

|

Name: Janine Castro School: Homestead Senior

|

|

Research Question(s): How effective is the use of positive behavior interventions to improve reading skills for students with special needs?

|

|

Intervention: Describe the intervention you will implement to accomplish the outcomes you seek for your students? The use of positive behavior intervention may help students improve their ability to focus on tasks and improve their study skills. Before implementing this intervention, the teacher had to find out why the behavior occurred, and when and how the challenging behavior happened. Then students were taught the appropriate response (desired behavior) and rewarded for the positive behavior. When the student reached his or her main goal, which was to minimize any disruption caused in the classroom or learning environment, and focus on their study skills, the intervention continued and students were reward with verbal praise, stickers, certificates, positive notes, and tokens to reinforce the students’ positive behavior. The use of positive reinforcement intervention was implemented during instructional time in the classroom for nine weeks.

|

|

Data Collection: Describe the specific approaches you will use to collect data before, during, and/or after your intervention. You need to “triangulate” your data; thus, you need at least 3 different data sources (e.g., tests, observations, interviews). Also, be specific about what each data source measures (e.g., you are using a test that measures reading comprehension or using observation to tally bullying behaviors). Next, describe the type of data that you obtain with each source (e.g., scores from a test of subtraction facts or a frequency of bully events observed). Data Source 1: Before applying my intervention, I met with the students’ teacher (three teachers in my unit) to analyze students behavior, especially the ones who had a serious problem. After identifying the students with behavior problems, I gave the class a worksheet to be discussed in the classroom asking about the consequences of having a disruptive behavior, and asked them to express themselves about it. During instructional time, I observed them and took notes of when and how the disruptive behavior started. The intervention was implemented for six weeks, after this period of time, based on teacher’s observation; students behavior was compare and find out if improvements were made. Data: Students behavior was observed and data was collected to determine if there was an improvement in students’ behavior. If the desired behavior occurred after the intervention was applied, then the intervention was successful. Data Source 2: During the nine weeks of intervention, I encouraged students to behave properly and use their time to perform the best they can during instructional time. I recorded the times students’ behavior was disruptive. The observations were conducted in the classroom for 30 minutes daily. Data: Event recording/ Latency recording. Data Source 3: The teacher asked students to self-reflect about their behavior and complete a worksheet about behaviors that they should have in the classroom and school facilities. Then after three weeks I asked them to do the same and compare their behavior in the last three weeks and finally at the end of the nine weeks I asked them to complete a worksheet about their behavior in the school and compare the last and the first week. Data: Latency recording: This allowed the teacher to time how long it took the students to start a behavior or skill after a stimulus (e.g., when they behaved well, the teacher praised them) was presented. |

|

Time Line(use separate form): The Time Line must include length of intervention and when materials (if needed) are prepared, when persons are notified and/or permissions are sought, and when you plan to collect all data – be very specific. |

Time line

|

Tasks |

Timeline |

Resources |

|

Notification to the school Principal

Informed parents about the study

|

October 2016

|

|

|

Met with my team to explain about the study and collecting data

|

December 2016 |

Meeting, sharing the implementation of positive reinforcement in the classroom. Action Plan, Methods, timeline, discussing about teachers support. |

|

Self-monitoring/reflection Worksheet given to my class to collect baseline data

Observed students’ behavior for frequency of disruptive/inappropriate behaviors

Implemented intervention: Discussed with the class about intervention being implemented and what rewards they will receive.

At the end of the week, asked reading teachers for students’ academic grades and the students point sheet results. |

Week of January 9, 2017

Week of January 17, 2017

|

Self-monitoring Worksheet

Pencils, sheets of paper.

Data collection forms, teacher observation.

Student rewards

|

|

Collect weekly observation data on frequency of inappropriate behaviors

At the end of every week, ask reading teachers for students’ academic grades

Every 3 weeks, students completed self-monitoring worksheets

|

Weeks of January 24-February 24 |

Data collection form

Self-monitoring worksheet |

|

Post intervention behavior observation

Gave students final student self-monitoring worksheet

Obtained grades from reading teachers |

Week of February 27, 2016 |

Data collection form

Self-monitoring worksheet |

Findings, Limitations, Implications

Data Analysis

The data collected for this action research study were analyzed interpreted using various different approaches. After meeting with the unit teachers and identifying students with behavior problems, the frequency on inappropriate behavior was recorded, during pre and post intervention, then was compared to find students improvement. A second data source was during the intervention; students were orally encouraged to behave well and their behavior was recorded in the classroom during 30 minutes.

Students were given a first self-reflect questionnaire with questions regarding their behavior in the classroom and school facilities and they completed it every three weeks and finally at the end of the study. The collected data in these questionnaires were compared during the whole process, finally students academic progress report was reviewed and compared at the end of the study with the grades students had before using intervention.

Findings

The findings on this study support the research found before initiating the intervention. Research supports the use of positive behavior intervention for special education students with varying exceptionalities (Yaeger &Walton, 2011). This intervention incorporates daily positive behavior during daily instruction, proving the desired behavior have occurred and students have reach their main goal, which is minimizing disruption caused in the classroom and focusing on their study skills. Improvement in the students’ behavior was notable. The reward systems (based on their behavior) have proved to be a very useful tool; students were eager to gain rewards and the disruptive behavior decreased as the intervention was implemented.

Positive behavior interventions were brought to the students in this study by using different resources like rewarding students verbally, with stickers, certificates, positive notes, call to parents to inform about the good behavior, and finally a fieldtrip to the Youth Fair. Supplementary, this study has considered how students were able to perform better in the classroom and school facilities,

This information provided an understanding of how each type of data have helped to answer the research question provided before the study:

Teachers’ Meeting. During the pre and post meeting most of the teachers’ input were about the intervention and how it will be used during instructional time, most of the responses from teachers in the post meeting were very similar, showing the process and the changes in students’ behavior, as most of them have improved.

Table 1

Classroom Behavior Observed During the Study

|

S T U D E N T S |

Students disruptive Behavior Occurs before intervention

|

Days 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5

|

Students disruptive Behavior Occurs during intervention

|

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11

|

Students disruptive Behavior Occurs After Intervention

|

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

|

#1 |

|

+ |

++ |

++ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

+ |

+ |

0 |

|

#2 |

|

0 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

++ |

|

0 |

+ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

+ |

|

+ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

0 |

|

#3 |

|

++ |

+ |

++ |

0 |

+ |

|

+ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

0 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

#4 |

|

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

|

+ |

+ |

++ |

+ |

0 |

+ |

|

+ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

+ |

|

#5 |

|

0 |

0 |

+ |

0 |

+ |

|

0 |

0 |

+ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

#6 |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

o |

+ |

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

+ |

0 |

|

#7 |

|

++ |

0 |

++ |

0 |

++ |

|

0 |

+ |

0 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

0 |

0 |

+ |

|

#8

|

|

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

|

++ |

+ |

0 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

0 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

None 0, Sometimes + (1-2 times), Excessive ++ (3 or more times)

Student’s Self-reflection Questionnaire.Students’ questionnaires were collected and analyzed. According the results, most of students noticed changes in their own behavior in the classroom and school facilities. It was critical the cooperation of the other two teachers in the unit, and after the intervention the desired behavior was perform not only in the classroom, but also in the other school facilities, fortunately this was happening.

Table 2 shows students’ responses to the pre and post questionnaire. Students showed a notable increase in appropriate behaviors. Some of the positive behaviors were their spam of attention improved during the instructional time; students were more capable to follow instructions before, during, and after academic classes. Some of them helped their classmates in situations when disruption could occurred, for instance during the transition from class to class, they waited for the bell, and then left the classroom, instead of standing next to the door before the bell rang. During the group work, students showed on-task behavior and cooperated to finish the activity.

Table 2

Pre and Post Responses on Students’ Questionnaire

|

Students |

#1 |

#2 |

#3 |

#4 |

#5 |

#6 |

#7 |

#8 |

|

Do you understand school and classroom rules? |

Pre – yes

Post-yes

|

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

|

Do you follow teachers’ instructions when first time given?

|

Pre- no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-no |

|

Do you ask for help when need it? |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

|

Do you realize when you are not behaving appropriate in the classroom? |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

|

Does inappropriate behavior occur most of the time? |

Pre-no

Post-no |

Pre-no

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

|

Do you try to correct your behavior? |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

|

Do you believe you can correct your behavior? |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

|

Does your teacher help you to improve your behavior in class? |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

|

Do you behave inappropriate in other places? |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

Pre-no

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

Pre-no

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

Pre-no

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-no |

|

Do other students help you to improve your behavior? |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

|

Do you find easy to improve your behavior? |

Pre–no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-no |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

Pre-no

Post-yes |

|

Do you think behaving better will improve your grades? |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

Pre-yes

Post-yes |

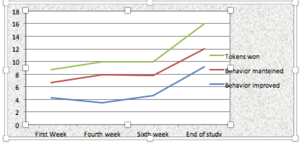

Student Point Sheet and Tokens. The point sheet was incorporated as a positive reinforcement during the intervention and it was recorded weekly for each student. This strategy was intended to support teachers, and students with challenging behavior; they were given a point sheet to be graded by the teacher at the end of each period of class, for instance if the student was on time, and had a good behavior he/she won two points per block, at the end of the day, they had a chance to win ten points. At the end of each week the point sheet was given to the teacher and students, who had won at least six or more points each day, receive incentives, such as: stickers, breakfast, game boards, and call to parents to let them know about the good behavior, they also had the opportunity to be a teacher’s aide. Students showed a desire to get incentives, they were prompted to be on time in each class and be on-task, as they knew they would receive an incentive by the time the period of class ended, the number of students who were late decreased. The data show an increase of the desired behavior in class since the intervention occurred; it also showed an overall increase of tokens, which were earned from the beginning to the end of the positive behavior intervention. Figure 1 bellow shows the graph created to display data.

The students’ tokens were used as a positive reinforcement during this intervention, teachers reward at the end of the week students who showed the desired behavior, and the result showed an overall increase in tokens earned since the beginning to the end of the intervention. Teachers made note of students who won them and was recorded weekly. In table 2 improvement in behavior showed. Table 2 shows the improvement in behavior and Figure 1 shows the number of tokens earned weekly.

Figure1. Number of students’ tokens earned weekly.

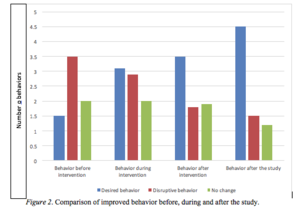

Anecdotal Records, Teacher Checklist and Journal. These data collection forms were extremely important to the teacher; they were a source to analyze the improvement made during the study. There were some days when intervention did not work as expected, after reviewing the data, the results show the use of positive behavior intervention proved to be an excellent method for this group of students, as a result there are many positive changes in the students’ behavior. The students are aware of the consequences of behaving as expected. Most of them were eager to start the classroom activities and learn in a relaxing and inviting environment. Additionally, according to teachers’ input and grades report, students who have received positive behavior intervention as a reinforcement, were more likely to improve their study skills rather than those who only have teachers’ support. Figure 2 below show the graphs created to display data. Importantly, most students showed in improvement in their grades for their reading classes. This supports the idea that positive behavior supports can motivate students to improve their study skills, and this may help them earn better grades.

Figure 2. Comparison of improved behavior before, during and after the study.

Table 3

Students’ Reading Grades

|

|

Students Grades Before Intervention |

Students Grades During Intervention |

Students Grades After Intervention |

||||||

|

Students |

week 1 |

Week 3 |

week 5 |

Week 1 |

week 3 |

week 5 |

week 1 |

week 3 |

week 5 |

|

#1 |

Z |

C |

C |

B |

C |

B |

B |

A |

B |

|

#2 |

Z |

C |

C |

A |

B |

B |

A |

B |

A |

|

#3 |

C |

Z |

C |

C |

C |

B |

B |

B |

A |

|

#4 |

C |

C |

C |

C |

B |

B |

B |

B |

B |

|

#5 |

C |

C |

Z |

Z |

C |

B |

B |

B |

A |

|

#6 |

B |

Z |

B |

C |

B |

B |

B |

B |

A |

|

#7 |

Z |

Z |

C |

B |

B |

B |

B |

B |

A |

|

#8

|

C |

Z |

C |

B |

C |

B |

B |

B |

A |

Limitations

This study was conducted in a high school with special education students who were on a Special Diploma track and were using a modified curriculum and accommodations as stated in their Individual Educational Plans (IEPs), the study was conducted with the purpose to improve these students’ behavior, but it did not suggest using these strategies will work all the time with any students with special needs. Learning styles were diverse and each student have a unique way of learning, based on their culture, likes and dislikes, and their physical, intellectual or sensory disabilities. The purpose of this study was not to take a broad view for other classes.

The intervention had others limitations such as students’ participations, attendance and interruptions due to school activities and meetings, nevertheless the research centered on the same theme, based on students’ performance and abilities. Parents were cooperative and most of them showed support and got involved, but here were some cases when circumstances out of my control, the cooperation did not occur as expected.

Implications

Students who participated in this research, have started using a self-reflective handout, where they can record their daily behavior progress, other teachers in the unit are using the point system and have added some of the strategies and rewards in their daily teaching, as a result, students are more confident and feel motivated to learn. The use of positive behavior intervention showed an improvement in students’ behavior and study skills, classroom teachers should consider using these strategies to help students stay on task and possibly improve their academic grades.

Dissemination

This study results have been share with students in the unit, the program specialist in the school and special education teachers and with graduate students at Florida International University (FIU). The results have also been shared with a former colleague who is now working with the Ecuadorian education minister. The study will be shared with faculty members who are interested in the results and also in using strategies to improve students’ behavior in the classroom.

References

Alderman, M.K. (2008). Motivation for achievement: Possibilities for teaching and learning.

New York, NY: Routledge.

Conroy, M. A., Dunlap, G., Clarke, S., & Alter, P. (2005). A descriptive analysis of behavioral

intervention research with young children with challenging behavior. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 25, 157-166.

Kaniuka, T. S. (2010). Reading Achievement, Attitude Toward Reading And reading Self-

Esteem of Historically Low Achieving Students. Journal of Instructional Psychology

McKevitt, B., & Braaksma, A. (2008). Best practices in developing a positive behavior support

system at the school level. In A. Thomas & J. P. Grimes (Eds.), Best practices in school

psychology V, (pp. 735-748). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

National Association of School Psychologists. (2002). Social Skills: Promoting Positive

Behavior, Academic Success, and School Safety. Retrieved from https:// www.naspcenter.org /factsheets/socialskills_fs.html.

Ruef, M. B., Higgins, C., Glaeser, B., & Patnode, M. (1998). Positive behavioral support:

Strategies for teachers. Intervention in School and Clinic, 34 (1), 21-32.

Sugai, G. & Horner, R. R. (2006) A promising approach for expanding and sustaining school-

wide positive behavior support. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(3), 255-265.

Polirstok, Susan & Gottlieb, Jay. The Impact of Positive behavior Intervention Training for

Teachers On referral Rates for Misbehavior, Special Education Evaluation and Students Reading Achievement in the Elementary Grades. International Journal of Behavior Consultation and Therapy. Volume 2, No 3, 2006

Williams, K. & Williams, C. (2011). Five key ingredients for improving student motivation.

Research in Higher Education Journal. Retrieved from

www.aabri.comwww.aabri.com/manuscripts/11834.pdf

Yaeger. D.S. and Walton, G.M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education:

They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81, 267-301.

Appendix A

Student Self-Reflection Questionnaire Sample

|

Student Name |

BLK 1 |

PASS |

BLK2 |

PASS |

BLK3 |

LUNCH |

PASS |

BLK4 |

DISMISSAL |

BONUS |

TOTAL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appendix B

Student Point Sheet Sample

Points: Total of 10 points

2- Attendance/Promptness

2- Engagement in class

2- Listening skills

2-Preparation

2 – Following classroom rules /school rules

DATE: ___/___ to ___/___

Appendix C

Students’ Token System

|

Student name |

Week 1 (Stickers) |

2 Breakfast |

3 (teacher’s aide) |

4 (20 minutes-computer break) |

|

# 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

#2 |

|

|

|

|

|

#3 |

|

|

|

|

|

#4 |

|

|

|

|

|

#5 |

|

|

|

|

|

#6 |

|

|

|

|

|

#7 |

|

|

|

|

|

#8 |

|

|

|

|

Appendix D

Administrative consent for action research

October 13, 2015

Good Morning Mr. Munoz

As I explained to you earlier, I will be conducting a study in my classroom as part of completing my master’s degree. The study is based on observation to reinforce positive behavior in order to improve study skills, the positive intervention to be used, will include praising students or giving them stickers, tokens, certificates, and a field trip to the Youth Fair.

The participants will be my students and myself who will conduct the study.

Thank you.

Mrs. Janine Castro

SPED. Teacher

Room # 623

(305)245-7000 Ext.2273

“Home of the Broncos”

Appendix E

Thank you note to the principal

Castro, Janine L.

To:

Munoz, Guillermo A.

Dear Mr. Munoz

I want to thank you for all the support and help I have received to conduct the study in my classroom, in order to complete my master’s degree at FIU.

I am very pleased to inform you the results of the study were very satisfactory, the students’ behavior improved tremendously. The teachers in the IND unit have been using positive reward, tokens and finally we took our class to the Youth Fair.

During our meetings we discussed about all the positive changes, and how the children are more confident to learn in a safe and relaxing environment, it was a very rewarding experience for all of us.

Once again thank you very much,

Sincerely

Ms. Janine Castro

SPED. Teacher

Room # 617

(305)245-7000 Ext.2284

“Home of the Broncos”

Some people go into teaching because it is a job.

Some people go into teaching to make a difference………. Harry K. Wong

By Chelsie Madiedo

Background

Augmentative and Alternative Communication methods are very effective when working with non-verbal ASD children. According to American Speech Language Hearing Association, “Augmentative and Alternative Communication methods (AAC) includes all forms of communication (other than oral speech) that are used to express thoughts, needs, wants, and ideas. We all use AAC when we make facial expressions or gestures, use symbols or pictures, or write” (American Speech Language Hearing Association, 2017). “There is evidence that children diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder often have restricted verbal communication” (Bedwani,2015). Therefore, communication methods are imperative for non-verbal students. When researching the effectiveness of one of the AAC Programs (LAMP), eight children that were limited with communication skills previously showed gains after using the Program LAMP for a total of five weeks.

Secondly, non-verbal students have difficulty expressing their needs and wants on a daily basis with their natural voice. “Children require the use of augmentative and alternative communication to help them communicate” (King, 2012). However, there is a problem, since using AAC as far as a form of communication, is especially difficult. “One way that has seemed to help is by providing peers with knowledge and skills on how to interact with children who use AAC, and has produced positive results” (King,2012).

Case Study

Next, an experiment on a four -year old boy who had autism and used an AAC device, both in school and home, were investigated. “According to the experiment, the child’s mother was taught to use 4 naturalistic teaching strategies that incorporated a picture exchange communication system during 2 typical home routines” (Nunes,2007). According to the data and the baseline data that was collected, it showed the increase in the child’s initiations and responses when using the PECS system.

Different Forms of Augmentative Communication Devices

Furthermore, children usually demonstrate frustration or irritability when they are not able to communicate effectively. “Identifying and using suitable communication enhancement and augmentative and alternative communication supports is essential to achievement of positive outcomes for these learners” (Simpson,2012). “A critical component of the AAC device assessment process is to match the amount and kind of language in the user’s brain to the amount and kind of language available in a particular AAC device so the individual can generate language as efficiently and effectively as possible” (“Types of AAC Devices,”n.d.). Augmentative communication devices are broken down into three categories low tech, hi tech and symbols. The augmentative communication I have used in my classroom is PECS. PECS stands for Picture Exchange Communication System. PECS is a modified applied behavior analysis program. Although PECS was not created as a speech program, some non-verbal children picked up speech with the program. After researching all the different augmentative and alternative communication methods I feel that PECS is the most reliable and affordable method to use with non-verbal children.

Language Representation in AAC Systems

When figuring out what AAC device or system you will be implementing with the child you first need to see where the child is linguistically. “Success in life can be directly related to the ability to communicate. Full interpersonal communication substantially enhances an individual’s potential for education, employment, and independence. Therefore, it is imperative that the goal of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) use be the most effective interactivecommunication possible. Anything less represents a compromise of the individual’s human potential” (Hill, 2017). There are three basic methods of language representation single meaning pictures, alphabet based systems, and semantic compaction. “With single meaning pictures, each picture means one word. Alphabet-based systems include spelling, word prediction, and letter codes. Semantic compaction (Minspeak) is the only patented system and is based on multi-meaning icons”(Hill,2017).

Outcomes

Testing the effectiveness of both the devices and services is imperative. “Outcome measures are objective criteria, usually developed during the assessment and recommendation process that can be used to judge the effectiveness of both devices and services” (Hill,2017). Therefore, the language representation method determines if the outcome is achievable and observable. The goal is for the child to be able to communicate using this device on a regular basis.

AAC and Behavior

Implementation off AAC devices can decrease unruly behaviors. Since the child has a way to express themselves they can engage in positive social interaction with peers or adults. Majority of the problematic behavior in the ASD population is caused because the child is not able to express themselves verbally and gets frustrated. Since the frustration builds up overtime so do the negative behaviors and emotions. According to a study 103 children participated in a study addressing behavior and communication. “The 103 children who participated were six years old or younger, had developmental delays, and engaged in destructive behaviors such as self-injury. The core procedures used in each study were functional analyses (FA) and FCT conducted by parents with coaching by the investigators. The overall results of the projects showed that the FA plus FCT intervention package produced substantial reductions in destructive behavior (M = 90 %), which were often maintained following treatment” (Wacker, Schieltz, Berg, Harding, Dalmu, Lee,2017).In conclusion, when a child finds an AAC system or device that suits them it becomes a great relief. The decrease in problem behaviors is due to the increase in being able to communicate effectively.

References

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). (1997). Retrieved May 20, 2017, from https://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/AAC/

Bedwani, M. N., Bruck, S., & Costley, D. (2015). Augmentative and alternative communication for children with autism spectrum disorder: An evidence-based evaluation of the Language Acquisition through Motor Planning (LAMP) programme. Cogent Education,2(1). doi:10.1080/2331186x.2015.1045807

King, A. M., & Fahsl, A. J. (2012). Supporting Social Competence in Children Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication. TEACHING Exceptional Children,45(1), 42-49. doi:10.1177/004005991204500106

Logan, K., Iacono, T., & Trembath, D. (2016). A systematic review of research into aided AAC to increase social-communication functions in children with autism spectrum disorder. Augmentative and Alternative Communication,33(1), 51-64. doi:10.1080/07434618.2016.1267795

Martin, C. A., Drasgow, E., Halle, J. W., & Brucker, J. M. (2005). Teaching a child with autism and severe language delays to reject: direct and indirect effects of functional communication training. Educational Psychology,25(2-3), 287-304. doi:10.1080/0144341042000301210

Nunes, D., & Hanline, M. F. (2007). Enhancing the Alternative and Augmentative Communication Use of a Child with Autism through a Parent?implemented Naturalistic Intervention. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education,54(2), 177-197. doi:10.1080/10349120701330495

Simpson, R. L. (2011). Meta-Analysis supports Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) as a promising method for improving communication skills of children with autism spectrum disorders. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention,5(1), 3-6. doi:10.1080/17489539.2011.570011

Types of AAC Devices. (n.d.). Retrieved June 01, 2017, from https://www.augcominc.com/whatsnew/ncs5.html

Wacker, D. P., Schieltz, K. M., Berg, W. K., Harding, J. W., Dalmau, Y. C., & Lee, J. F. (2017, March 18). The Long-Term Effects of Functional Communication Training Conducted in Young Children’s Home Settings. Retrieved June 01, 2017, from muse.jhu.edu/article/650676/pdf

About the Author

My name is Chelsie Madiedo and I am currently a graduate student at Florida International University. I graduated with my Bachelor’s Degree in Early Childhood and was Summa Cum Laude of my class. Education has always been a very big part of my life. I am currently seeking my Master’s Degree in Special Education with an Autism Endorsement at Florida International University. Once I graduate I plan on getting a specialist and doctorate degree specializing and concentrating in Autism. I am currently teaching an Autism Level 2 classroom with three students one who is non-verbal. I have definitely found that using augmentative communication devices and supports really helps the child be able to communicate more efficiently. I hope you enjoy reading my article.

By Louris Otero

Introduction

Parent Satisfaction with the current education system and programs for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder varies. Most of the literature suggests that parent satisfaction is mostly high. But a careful review of the literature also implicates that changes can be made in the areas of teacher training, parent communications to increase parent involvement and increased funding for families with unmet needs in an effort to further improve parent satisfaction. There are issues with the readability of parental safeguards and a lack of general knowledge about ASD. There is yet another concern for parents who view caring for their disabled child as a major burden, and the lack of support services as a child ages out of the system. All is not lost, however. Researchers have found possible solutions as the following review of the literature confirms.

Parental Satisfaction: Issues and Solutions Emerge

Star and Foy (2010) conducted a survey of 144 parents of children on the autism spectrum with the purpose of delving into the level of satisfaction parents experience with the education that their child is receiving. Various research questions were addressed including: how fear and resentment is perceived, which factors contribute to their child’s suspension from school, level of satisfaction with their child’s education, how parents perceive that their child’s school is able to maximize their child’s education, and finally, what the long term goals are for their children (Star and Foy, 2010). The researchers placed notices in the newsletters of autism support groups asking for volunteers for the study. Researchers discovered that most of the families had children in younger children. The average age of the children was 8 years. The article cited that a survey of 106 open-ended and Likert- type questions was used; both satisfied and dissatisfied participants responded.

The themes that emerged from the survey responses were as expected and were in line with the themes that emerged in in a similar study conducted in 2006 also by Starr and Foy. Parents reported dissatisfaction stemming from low expectations, lack of knowledge about ASD, lack of collaboration and parent communication, and lack of knowledge of the educational program (Star and Foy, 2010). They also reported that the lack of teacher education cause their child to be suspended from school for perceived aggressive behaviors (Star and Foy, 2010). Most suspensions were unofficial or “voluntary” as parents were asked to take their children home when they exhibit undesirable behaviors. Resentment was the most commonly cited negative attitude. The parents reported that teachers resented having an autistic child in their class and the time and effort that the autistic child demanded (Star and Foy, 2010). Most parents reported being dissatisfied with how the education system was meeting their child’s needs (Star and Foy, 2010).

The one solution that kept coming up in parent’s comments was the need for teacher education (Star and Foy, 2010). Parents repeatedly cited that improved teacher education would all but eliminate many of the emerging issues (Star and Foy, 2010). One family stated that they would deal with the same issues year after year because teachers were not aware of their child’s disability, they would have to educate the teachers and be the experts in the room (Star and Foy, 2010). Another family suggested that a school-wide seminar is offered annually to help educate the teachers as to evidence-based practices and autism spectrum disorder in general (Star and Foy, 2010).

Finally, most parents expressed future goals as wanting their child to be as independent and happy as possible (Star and Foy, 2010). The limitation of this study is in its sample. Most students were young and male. The sample was small and lacked diversity. Although the sample was small, it was interesting that only one parent chose not to respond to open-ended questions with comments (Star and Foy, 2010). Furthermore, it would be interesting to see the study duplicated with a greater sample of the population along with greater cultural diversity.

Issues with Readability and Parental Safeguards

Mandic, Rudd, Hehir and Acevedo-Garcia (2010) obtained the procedural safeguards from all 50 states including the District of Columbia in an effort to evaluate them using the SMOG readability formula. The purpose of this study was to determine the reading level needed in order to comprehend the procedural safeguards. Mandic, et al. (2010) used the data from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy to estimate the level of literacy among parents aged 24-49 (Mandic, et al. pp. 198). The authors determined that more than half of the safeguards were written at a college reading level and another 39% were written at a graduate or professional reading level (Mandic, et al. pp. 198). Only a scant 6% were written using a high school reading of the level of 10-12th grade (Mandic, et al. pp. 198).

The authors determined that their findings were consistent with previous studies by Fitzgerald and Watkins (2006) which also found that procedural safeguards are written at levels thought to be unnecessarily high. This study by Mandic, et al. found the procedural safeguards to be written at even higher levels than what Fitzgerald and Watkins found. The result being that families’ rights are being neglected because of the reading proficiency necessary in order to comprehend the procedural safeguards.

This study by Mandic, et al. has several limitations. One limitation being that only a sample of the document was used to determine readability. Another was that parent involvement was not measured as a result of poor readability. Finally, this study did not take into account support from advocacy groups that are possibly made available to parents of children with disabilities.

The implications are that procedural safeguards need to be understood not just by parents of all educational backgrounds, but by student self-advocates. Additionally, parent involvement may be adversely affected by a parent’s inability to make sense of their rights and responsibilities. Finally, the recommendation set forth in this study is simple. Procedural safeguards should be written in plain language. Language should be easy to understand, read and use. Safeguards should be written using short sentences and common everyday words that anyone without a college education is able to read (Mandic, et al. pp. 201)

Parental Involvement and the Pre-Referral Process

In an article about parental involvement in the pre-referral process by Chen and Gregory (2010), the question of how much parental involvement in the pre-referral process is discussed and dissected. Chen and Gregory start out by explaining that PITS (Pre-referral Intervention Teams) or group problem-solving models, and RTI are widely used in place of the discrepancy model as a response to inappropriate referrals of minority students. The reasoning is that working in teams of professionals offers the best most comprehensive model for collaboration between professionals and parents. The literature suggests that although parents may be invited to participate in the pre-referral process, few actually attend (Wilson, Gutkin, Hagen, & Oats, 1998). Furthermore, 2 other studies suggest that when parents are involved, parents seem more satisfied with their child’s progress and even felt that their child was more successful because the intervention plan met their child’s needs. (McNamara, Telzrow, &DeLamatre, 1999). This study seeks to consider the influence of parental involvement by hypothesizing, as previous studies suggest, that the level of parental involvement can be used to predict parent satisfaction, the number of special education evaluations, and alignment between PIT interventions and the child’s presenting problems (Chen & Gregory, 2010).

The participants included 88 elementary school cases during the 2005-2006 school year. Of the 88 cases, 51 were male and 37 were female. Demographically, 69% were white, 21% were black, 8% were Hispanic, 1% were Asian, and 1% was unknown. The cases were reliably coded (Chen & Gregory, 2010). A total of 129 records were collected, while 88 were determined as eligible and subsequently reliably coded while intercoder reliability was established (Chen & Gregory, 2010). Independent measures such as race, gender, and parent involvement were evaluated (Chen & Gregory, 2010). Additionally, coders evaluated to the degree to which parents reported implementing the PIT interventions that the team recommended using a 3-point scale – 0 = no implementation, 1 = poor quality implementation, and 2 = high-quality implementation (Chen & Gregory, 2010). The records were evaluated for dependent measures such as intervention alignment, the frequency of special education evaluations, and missing data (Chen & Gregory, 2010).

The study determined that parents were present during initial and follow-up meetings in 43% of the cases. Parents were not present for either meeting in 14% of the cases. The results of parent involvement and intervention implementation were “significantly and positively correlated” (Chen & Gregory, 2010). Findings showed that parent involvement positively affected the level of parent satisfaction and the quality of interventions implemented in the home (Chen & Gregory, 2010). Parents may offer unique insights, perspectives and information to the PIT team making the collaborations more valuable and effective (Chen & Gregory, 2010). Additionally, the likelihood of referrals for special education evaluations was fewer in cases where parent involvement was high (Chen & Gregory, 2010).

The limitation of this study are several including a lack of data regarding parent behavior during PIT meetings, a lack of independent verification of parent implementation, parent demographic information was not collected, and the sample group of participants was very small.

The implications of this study were also interesting. The study demonstrated that the potential for influence by the parents during the PIT process can be significant and positive. Districts and schools should encourage parents to attend meetings by extending invitations early and often. It should be suggested that this study is conducted in the future using a larger, more diverse sample size, and parent demographics such as income, education, familiarity with the process and behavior should be taken into account.

Issues with Unmet Needs

In the article Beyond an Autism Diagnosis: Children’s Functional Independence and Parents’ Unmet Needs by Brown, Ouellette-Kuntz, Hunter, Kelley, Cobigo & Lam (2010), the authors attempt to draw a comparison between the level of independence of a child with Autism Spectrum Disorder and the parents’ unmet needs (Brown, Ouellette-Kuntz, Hunter, Kelley, Cobigo & Lam, 2010). The study sets out to determine how functional independence, parent perception of the impact of ASD on the family, needed services is associated with unmet needs (Brown et al., 2010, p. 1292). Unmet needs are defined as the cost of private therapies, the limited, publicly-available school-based supports such as occupational, physical, or speech and language therapies, the cost of adaptive technology, and the age restrictions on certain services (Brown et al., 2010,). Functional independence is determined by a child’s overall adaptive skills such as self-help, ability to communicate and socialize, and the frequency and severity of undesired or challenging behaviors such as self-injury, non-compliance, or inappropriate vocalizations (Brown et al., 2010).

The participants were a cross-section identified from two separate Canadian epidemiologic and autism research databases. (Brown et al., 2010). The participants were gathered via a telephone call or mailings. The criteria for participation included parents or legal guardians of school-aged children between six and 13 years of age who had been diagnosed with ASD, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified. Each participant filled out the Family Needs Questionnaire (Siklos and Kerns, 2006), the Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised (Short Form) (Bruininks et al. 1996), the Impact on Family Scale (Stein and Jessop, 2003), and other forms for the purpose of collecting information about family characteristics.

The other characteristics measured were gender, age, grade level, ASD diagnosis, the presence of any comorbidities, use of medications, behavior or attention problems, and time since diagnosis was made. The parental characteristics gathered were marital status, income, education, changes in employment because of having to care for a child with ASD, having another child with ASD, and location of residence (Brown et al., 2010, p. 1294).

The study by Brown et al. (2010) found a “linear relationship between functional independence and unmet needs” (p. 1299). This means that the more functionally independent a child is, the fewer unmet needs the parents reported, and conversely, the more functionally dependent a child with ASD is the more parents reported unmet needs. This also depended on whether the family felt that caring for their child was burdensome. If the family did not feel that caring for the child was a burden, they reported fewer unmet needs and vice versa. Also, families with older children, grades 4-8 appeared to have greater unmet needs than those with younger children in grades 1-3. This could be because the needs of younger children were provided for through the school system, and as children get older, fewer services are offered through the school system.

The major limitation of this study was the low response rate of the participants and the number of characteristics analyzed. The study also found that parent perception of burden has a greater impact on reported unmet needs. The major implication of this finding results in perhaps signaling a need to devote greater resources to families whose children present a greater burden because their ability to be functionally independent is less. Finally, because perceived needs are fundamentally subjective, perhaps further research may be valuable in the area of “unmet need bias” (Brown et al., 2010, p. 1301).

Professional Development, EBPs, and Implementation

Implementation Science, Professional Development, and Autism Spectrum Disorders by Odom, Cox, and Brock (2013) in conjunction with the National Professional Development Center on ASD seeks to provide evidence that the use of implementation science with regard to professional development in the area of evidence-based practices in programs designed specifically for students with ASD increase positive results and family satisfaction. The authors seek to show that by using implementation science to enhance a program by increasing the adoption of EBPs by educators in their classrooms student goal attainment and progress will increase (Odom, Cox, & Brock, 2013).