Education Through Music: Teaching Music to Students with Severe Autism Spectrum Disorder in Public Elementary Schools (Part 1)

By Aygul Hecht, Ph.D.

This issue of NASET’s Autism Spectrum Disorder Series was written by Aygul Hecht, Ph.D. In the US public school system, some students attend the general education classes, while others may receive instructions designed for students with special needs. Today, public school educators must adapt to educate students with disabilities (SWDs) in the least restricted environment settings. “Federal law requires that SWDs be educated in separate settings only when the nature or severity of their disabilities is such that the regular educational environment is not practical, even with the use of supplementary aids and services.” (Overview of Special Education in California, 2013). The special education teachers are trained and educated to teach students with different disabilities, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but meanwhile some other teachers, like music or art teachers, face a lot of problems due to lack of training and knowledge of teaching students with special needs. In this article Dr. Hecht will briefly describe what kind of problems faced when teaching students with severe ASD who were not qualified to be mainstreamed and why Dr. Hecht created and established the methodology to successfully teach music to exceptional students. This article will highlight only one aspect of the music lessons where it focused on teaching steady beats and rhythm to students with severe ASD.

Abstract

In the US public school system, some students attend the general education classes, while others may receive instructions designed for students with special needs.

Today, public school educators must adapt to educate students with disabilities (SWDs) in the least restricted environment settings. “Federal law requires that SWDs be educated in separate settings only when the nature or severity of their disabilities is such that the regular educational environment is not practical, even with the use of supplementary aids and services.” (Overview of Special Education in California, 2013)

The special education teachers are trained and educated to teach students with different disabilities, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), but meanwhile some other teachers, like music or art teachers, face a lot of problems due to lack of training and knowledge of teaching students with special needs. In my article I will briefly describe what kind of problems I faced when I started teaching students with severe ASD who were not qualified to be mainstreamed and why I created and established the methodology to successfully teach music to exceptional students. In this article, I will highlight only one aspect of my music lessons where I focused on teaching steady beats and rhythm to students with severe ASD.

Introduction

When I accepted the offer from one of the largest and the wealthiest school districts in Orange County, CA, I got excited. Having more than 10 years’ experience in teaching music to elementary level students, I was eager to share my music experience with students in a traditional classroom setting. However, instead, I was asked to teach “SAC” classes, K-3. When I asked around what “SAC” stands for, no one was able to tell me until I met my first class and asked the special education teacher who told me that SAC stands for “Structured Autism Class”, which was a new name for the special education class.

My first month of teaching SAC classes was a complete disaster. The younger age students were running out of the class or sticking their head out of window or wandering around the room and touching everything and making noise. Some of the older students sat down quietly but showed no interest in music at all. Some students cried or made loud noises as soon as they entered the music class. I felt like I was a failure, even though I was diligently making my lesson plans with selection of the songs and music examples appropriate to the age and grade of the students. I admit, I saw no improvement within a few months.

I approached the administrative staff and personally requested training. Their answer was “Orff Workshops” or ‘Kodaly Workshops”. Attending “Orff” and “Kodaly” classes did not meet my needs because these workshops were designed only for teaching music in the traditional classroom setting.

After a few months, I deleted all my lesson plans with the sign “IT DOES NOT WORK!” and I started designing new lesson plans from scratch. I visited public libraries and read all available materials and books about “Autism” and “Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder”. However, to my disappointment, I found very few or practically no materials on the topic that I was interested in, “Teaching Music to Students with severe ASD in the Public-School Setting”. Somehow, all the materials that I read and analyzed were realistically impractical or contained hypothetical theory that had no usage or application in my classroom. There are plenty of research-based articles about teaching music to special education students. However, all of them are written either by the music therapists who see kids on an individual basis a few times a week or the research-based articles written by the professors at universities whose scholarly approaches to the problem are too advanced for the elementary school teachers.

Here is one of the examples that may be useful for music therapists but impractical within the public-school setting. “A 12-year-old boy with autism is profoundly deaf. The music therapist instructs him to rest his chin atop the body of a cello, his face inclined toward the instrument’s neck. As the therapist guides him in moving the bow across the strings, the vibrations travel up his jawbone to the inner ear, and the boy “hears” music for the first time.” (Chase, 2009)

The example above is exciting. It is very innovative and very creative. Yet, it is still unrealistic within the public- school setting. First, per the school requirements, there is only a 30-minute class per week. Secondly, I must deliver the lesson plan to not one individual, but a large group of students with special needs. Thirdly, I don’t have the cello(s) or any other instruments to instruct my students to “rest their chin atop the body of cello” or any other instruments. And last, I must follow the curriculum as it is mandated by the school district. So, there are limitations and strict rules what I can do within the 30-minute of the class with a big group of exceptional students.

The university research-based articles and materials also did not help me at all. For example, in their article “Music and Social Skills for Young Children with Autism: A survey of Early Childhood Educators”, Anna Archontopoulou and Potheini Vaiouli summarized the survey that they conducted to answer the question, “What is “a promising method for supporting social and academic growth for all learners, including those with ASD?” (Archontopoulou, Anna and Vaiouli, Potheini, 2020). The special education teachers participated in the survey. All participants agreed that music can be used as a tool for emotional and social development of the students with special needs. Yet, there is no description of the method or tool that music educators or special education teachers can use in practice. The “tool” or “method” terms expressed in very hypothetical, theoretical manner without any “down to earth” explanation or examples.

In her book, “Teaching Music to Students with Special Needs: A Practical Resource”, Dr. Hammel overviews the strategies of teaching music to students with mild disabilities who may qualify to receive instructions in the least restricted environment setting (Hammel, 2017). Dr. Hammel describes in details the individualized education plan (IEP) and 504 Plan process for a music educator who has mainstreamed students in her or his class. However, in my practice, due to the nature of my work as the itinerant elementary music teacher, I never participated in the IEP or 504 meetings and my students did not get qualified to be mainstreamed.

After my disappointment with literature and scientific research, I decided to use my experiences of personal observation and knowledge.

First, I began talking to the special education teachers and asked them a few questions about students’ behavior, interests, etc. This helped me establish a list of the needs of my students.

Yet, the most important step in my methodology was re-evaluation of my professional goal and resetting outcomes based on the new goal. My professional goal “Development of Future Musicians” that I set in the beginning of my teaching career did not coordinate with the criteria of my SAC students. The guidelines published by Legislative Analyst’s Office led me to pinpoint the new goal and restructure my methodology. The guidelines state, “Older SWDs Receive Services to Help Transition to Adulthood. One of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act’s (IDEA) goals is to prepare SWDs for success in life after high school, when the federal entitlement to special education services typically ends. As such, beginning when students are age 16, local education agencies (LEAs) are required to develop specific services in IEPs to help SWDs prepare for the transition to postsecondary activities….Transitional services typically include vocational and career readiness activities, college counseling, and training in independent living skills.” (Overview of Special Education in California, 2013)

The guidelines helped me to identify the keywords to set the new professional goal. These keywords were:

-

Transition to Adulthood

-

Success in life after high school

-

Age of 16

-

Independent living skills

“Preparing my students for success in life” became the motto of my teaching. By observing my students’ capabilities and potential, I set the goal to assist my students to develop skills that may help them to transit to adulthood without any stress or frustration. While they were still under the supervision of teachers and one-on-one aids, and “vocational and career readiness activities” were on the list of their long-term goals, I, as a music educator, was able to contribute to their developmental process immediately. I disagreed with the approach that only after age of 16 or high school graduation my students should receive the help to build social and survival skills. In this case, I agreed with Leo Vigotsky, whose constructivism theory stated that learners construct meaning only through active engagement with the world, in contrast to the methodologists who viewed the learners “as ‘an empty vessel’ to be filled with knowledge.” (Mcleod, 2024)

Classroom Activities: Teaching Steady Beats and Rhythm.

While I was still required to teach CA music core standards and curriculum, I approached the concept of the “Beat” and “Rhythm” through the view of an ordinary person. So, I associated the “beat” as a “strike” or “1” whole number”, meanwhile the rhythm I laid out as a sum of strikes, without taking into account the note values.

My goal was to teach the concepts of “steady beats” and rhythm as a pattern of whole numbers. The concept of whole number could help my students to: a) understand the money concept; b) read the clock/time and do independent shopping and understand banking transactions in their future.

After singing the “Hello” song, which was a routine process to start the class, I displayed on the screen the clock image with the clock ticking (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v4enYB8IwwE):

I reinforced the audio of clock ticking with patting and saying “Tick-Tack, “Time Clock, tick-tack, tick-tack”.

While the audio clock was playing, I added a new layer to patting steady beats: I said the simplest rhyme that I created to reinforce the steady beats concept and I yield this concept with the concept of the clock movements:

Tick-Tack

Tick-Tack

Tick-Tack

Steady Beats,

Steady Beats

We Are Making Steady Beats

1-2-3-4-

We Are Making Steady Beats

Tick-Tack

Tick-Tack

Tick-Tack

I associated the steady beats with the clock and with the sequence of whole numbers: 1-2-3-4. All my students eventually engaged in this exercise.

After a few months, all my students were able recognize the clock and automatically patted the steady beats, and the speaking students memorized and said the rhyme out loud.

In addition to steady beats rhyme, I added one more layer: a singing voice. While I kept patting the steady beats and I was singing the nursery rhyme, “Are You Sleeping Brother John?”

I chose the song for a reason: the simple melody and echo features or call/response form, allowed me to teach the steady beats and echo concepts and motivate my nonverbal students to respond to singing. Eventually, after a few classes, my students echoed me back with response and my nonverbal students started making some musical sounds to participate in singing.

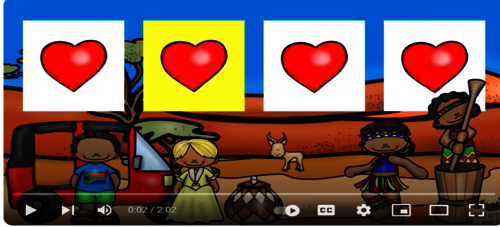

I continued working on the whole numbers concept in my next exercise. I found the Calypso children music piece (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G9Qpma4GM-A) with the display of four hearts per episode/slide that would stand for 1-2-3-4 numbers and 1-2-3-4- steady beats.

In this exercise, my students were able to pat the steady beats with the calypso music and match their beats with every moving “heart” image.

The visualization of steady beats accompanied by 4 hearts per slide helped students to feel the pulsation of the music, listen to the music, and play the steady beats. I reinforced the steady beats by pointing to each heart image and saying, “Tick, “Tack”, “Tick” “Tack”, and then, in the next episode/slide I said out loud the sequence of the numbers, ‘1, 2, 3, 4”. Even though my students did not see the whole- number display, they have already cognitively recognized the “moving” sequence from #1-4.

My next step in teaching the steady beats was the utilization of musical instruments. I had only a few tiny drums and they worked better than the rhythm sticks for my SAC students.

I found an educational video online that helped me to incorporate the concepts of whole numbers and steady beats. “Pete the Drummer” Video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfbLSvRFqtM) included the steady beats, the whole numbers, addition, and subtraction from # 1-10. The video was about 5-minutes long. However, I played only a few episodes/slides due to the time restriction.

By following the video rap, my students were playing the steady beats with the count from 1-8 and besides, they visualized the process of addition that had been displayed in each episode/slide of the video.

The visual aids play a very important role in my teaching methodology. All my exercises were accompanied by the visual aids. I did not make an exception when I introduced the “Rhythm” to my students.

First and most important, my goal was NOT to teach values of Quarter or Eight or Sixteen notes as I was doing it in my traditional setting classes; my goal was to develop sensory stimuli of my students that could help them to recognize and memorize the whole numbers. In this case, I made a different approach to the rhythm. I treated rhythm as patterns of whole numbers.

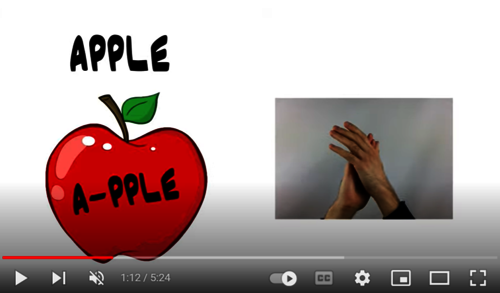

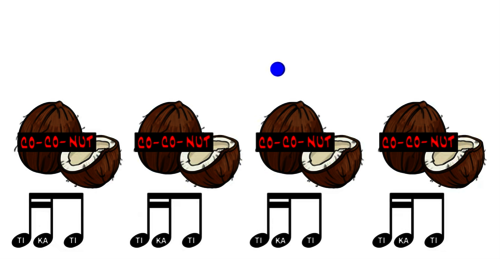

For example, I found an educational video online where the rhythm was introduced through the syllabus/strikes per word. Each word was a rhythmical display of fruit: pear, plum, mango, apple, coconut, blueberry, and watermelon (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=71fkBqZ_4K8)

Based on the number of syllables, each fruit/word contained a different rhythmic pattern.

My students were able to clap and say the words; my nonverbal students played the patterns, and they also used their iPad to find the fruit image from their device. Clapping the rhythm improved the memory of my students and stimulated their kinesthetic abilities and activated their cognitive responses to spoken words divided into the syllables. After clapping the patterns, my students and I played the rhythmic patterns on the drums.

Interestingly, after a few months, one of my students, Oliver, brought the numeric puzzle and matched the “fruity” rhythmic patterns with the whole numbers from his puzzle (Oliver processed the rhythm as the sum of strikes/syllables per rhythmical unit/word unlike the traditional view of the rhythm as note values (see example below). Another student, Junior, who barely spoke in my music class, used his finger to point to each note and pronounced each syllable according to the note value.

The song “How Many Fingers?” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xNw1SSz18Gg) concluded the steady beats/rhythmic part of my lesson plan. Despite several counting songs available online, I found this video more appropriate to my lesson plans because it contained 1) counting from 1-10; 2) introduced the anatomy: fingers and toes, 3) had the animated display of whole numbers with music background; 4) involved the fine motor-skills (my students had to use their fingers of left and right hands to count from 1-10) which, 5) involved the process of listening and repeating, 6) and involved the kinesthetic movements

(clapping, stomping, etc.). Yet, the most attractive part of the song was the simplest melody and funny characters that worked well for my students. My students responded very well by singing or “sounding” with the main characters of the song.

Conclusion

The rhythm and steady beats concept conclude the first part of the series of my methodology of teaching music to students with severe ASD. The purpose of this article is to help special education and music teachers to get some ideas about how to access students’ needs through music and deliver the subject matter or task through music. There is a lot of routine work, and repetition that must take place before the teacher can see “the sparks” in her or his students’ eyes. Yet, I did definitely see it after almost 9 months of tireless “redo, retry, and re-recreate” process.

In my next publications, I will share my ideas and techniques on how I taught “Emotions, Math and Music”, “Social” aspect and “Reading” concept through music to help my students to develop the basic independent living skills that could be useful in their near future.

Bibliography

Archontopoulou, Anna and Vaiouli, Potheini. (2020, July). Music and Social Skills for Young Children with Autism: A Survey of Early Childhood Educators. International Journal of Educational Research Review, 5(3), 190-207. doi:DOI:10.24331/ijere.730328

Chase, E. (2009, March 16). Using the language of music to speak to children with autism. Retrieved from NJ.com: www.nj.com/entertainment/arts/2009/03/using_the_language_of_music_to.html

Hammel, A. M. (2017). Teaching Music to Students with Special Needs: A Practical Resource (First ed.). Oxford Press University.

Mcleod, S. (2024, February 1). Constructivism Learning Theory & Philosophy Of Education. Retrieved from SimplyPsychology.org: Constructivism Learning Theory & Philosophy Of Education

Overview of Special Education in California. (2013, January 3). Retrieved from Legislative Analyst’s Office : www.lao.ca.gov/reports/2013/edu/special-ed-primer/special-ed-primer-010313.aspx

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Maria Pacino, Professor and Chair, Department of Library and Information Studies, at Azusa Pacific University, and Connie Prince at Los Angeles Public Library for their support and inspiration.

About the Author

Aygul Hecht is currently working as the public-school music teacher at Lancaster Unified School District and part-time librarian in one of the branches of Los Angeles Public Library.

Aygul Hecht received her BS in Music from Almaty State Conservatory (Kazakhstan) and PhD in Philosophy and Music from Moscow State University, Russia.

To download a PDF file version of this issue of NASET’s Autism Spectrum Disorder Series: Click Here

To return to the main page for NASET’s Autism Spectrum Disorder Series – Click Here