By Kathrina Bridges

Children with autism have greater severity of sensory difficulties. Having sensory processing disorders greatly affects students with Autism inside of the classroom. Children with Autism present severe difficulties regulating their senses in order to remain focus on the curriculum although best practices may be implemented in the classroom. Sweet (2010) found that children, who may have not yet learned how to independently compensate for sensory difficulties they experience, face challenges in focusing on learning in school. Sensory difficulties have been associated with emotional concerns, hyper-responsive sensory style in Autism was correlated with repetitive behaviors and have a tendency for sameness, decreased participation in activities and anxiety, and auditory filtering and under responsive/seeks sensation greatest impact on school functioning. The purpose of the study was to determine if students with Autism would benefit from implementing an in-class sensory activity schedule while using best practices for teaching students with Autism (curriculum, structure, routine and visual schedules).

Action Research Report Proposal: Sensory Bottles and Gel Bags

Children with Autism have greater severity of sensory difficulties. Having sensory processing disorders greatly affects students with Autism inside of the classroom. Children with Autism present severe difficulties regulating their senses in order to remain focus on the curriculum although best practices may be implemented in the classroom. Sweet (2010) found that children, who may have not yet learned how to independently compensate for sensory difficulties they experience, face challenges in focusing on learning in school. Sensory difficulties have been associated with emotional concerns, hyper-responsive sensory style in Autism was correlated with repetitive behaviors and have a tendency for sameness, decreased participation in activities and anxiety, and auditory filtering and under responsive/seeks sensation greatest impact on school functioning. The purpose of the study was to determine if students with Autism would benefit from implementing an in-class sensory activity schedule while using best practices for teaching students with Autism (curriculum, structure, routine and visual schedules).

Children with Autism have difficulties with sensory processing as well as sensory integration which affects their academic performance within the classroom setting. Sensory Processing is taking in information from all the sense and processing these effectively, taking in information from the right senses at the right time, and using the information effectively in day to day activities. Sensory Integration is the neurological process that organizes sensations from one’s own body and from the environment and makes it possible to use the body effectively within the environment. There are seven senses: inside senses include movement and balance, and body awareness. Outside senses include: tactile, auditory, visual, smell and taste. Sensory differences are more prevalent in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders than neurotypically developing children or child with other types of developmental disabilities. There are sensory subtypes in Autism: hyper, hypo, behavioral responses, over focused/pre-occupied/inattentive, links with specific modalities, links with motor planning and praxis, and enhanced perception linked with weak central coherence account.

The students that participated in the study were diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorders. There were 4 students who were in kindergarten and first grade. The students were taught with the general education curriculum within the general education classroom setting. The students received collaboration support for reading, language arts and mathematics. The students attended Somerset Academy Dade. Consent was obtained by administration, students and parents in order to implement the Sensory Activity Schedule (SAS) inside of the classroom. The researcher understood and took full responsibility of providing the necessary consent forms and materials needed to implement the Action Research Project within the classroom setting.

The researcher used the following activities within the current best practices used within the classroom setting along with a Sensory Activity Schedule: (a) sensory gel pads, (b) calm down bottles. The Sensory Activity Schedule was implemented using the following criteria: (a) administered by teacher, (b) before desk work and after desk work, (c) use classroom-based equipment, (d) 5-10 minutes.

Literature Review

Several studies suggest that students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have significant sensory difficulties. Students with ASD benefit from best practices implemented within the classroom setting such as curriculum, structure, routine and visual schedules. However, due to the sensory difficulties that students with ASD experience, it affects their ability to remain focused on their academic tasks and assignments.

Gonthier, Longuépée, and Bouvard (2016) found that individuals with ASD may have adverse reactions to certain stimuli such as lights, sounds and tactile contact with certain objects when compared to their neurotypical peers. Individuals with ASD often experience behaviors to avoid sensory input. This may lead them to experience pain or discomfort, lack of awareness and take part in spinning circular objects.

In reviewing the literature, students thrive from implementing routines and schedules within the classroom. Based on the information gathered from the literature review, some students with ASD require significant assistance with regulating their sensory input and output needs. The consideration of infusing a sensory activity schedule with the combination of using best practices for students with ASD include sensory gel bags and calm down sensory bottles.

Sensory Processing and its Relationship with Behavior Dysfunction

Twenty French inpatient care centers were assessed for the care they were providing, disorders with behaviors and the sensory profiles of the individuals. The centers selected for the study consisted of a large area which included both urban and rural populations, and they have been in operation for two to 29 years. The centers housed low functioning adults with ASD. Each participant completed a sensory profile. Different series of tests were conducted for the existence of sensory abnormalities in the ASD sample compared to the control group to gauge the normative cut scores of the sensory profile. Patients with ASD had a higher incidence of low registration behaviors and a less amount of avoiding, sensory and sensitivity behaviors when compared to the control group. Gonthier et al. (2016) claim that 60% of the participants within the study had a higher incidence of the scores in the subscale that examined sensation seeking. Furthermore, patients with ASD were more susceptible to experiencing difficulties in sensory processing. Based on the sensory profile of participants, Cluster A participants were over-sensitive, Cluster B participants were under-sensitive, Cluster C participants were under-responsive, and Cluster D participants demonstrated a balanced sensory profile, however, it was noted that Cluster D participants had a significantly higher level of verbal communication skills than the other three cluster participants. Sensory abnormalities were more predictive for different patterns of behavioral dysfunction. Patients with sensory sensitivity displayed behaviors of isolation, difficulties with social interactions, resistance to change, difficulties with sensory stimuli, not being able to initiate activities, and self-aggression. Sensation avoiding displayed isolation, difficulties with social interactions, and lack of direct eye contact. Sensation seeking did not display isolation, difficulties with social interactions or lack of direct eye contact, but displayed more aggressive, inappropriate social behavior, irritability, and emotional instability. Based on the data, the study confirms that sensory abnormalities are more prevalent with low-functioning adults with ASD and essentially contribute to their behavior disorders. Gonthier et al. (2016) state that it is important to identify the sensory profiles of individuals to help determine their sensory dysfunction to help prevent certain behavioral disorders and assist them with the necessary long-term care. It is recommended from the current study to implement sensory-based intervention strategies to help counteract or diffuse the unwanted behavioral issues. Some strategies to help assist with counteracting unwanted behavioral issues would be adapting the environment to the sensory needs of the individual, teach coping strategies to help with sensory overload to specific stimuli, and providing them opportunities to engage in stimuli that are tailored to their individual needs.

42 adults with ASD who were high functioning participated in the study conducted by Mayer (2017) located in London, UK. Based on the results from the test group and control group, the autistic traits in adults correlated with sensory functioning are significantly higher than the adults tested in the control group which was neurotypical adults. Lower levels of autistic traits correlate with higher levels of sensation seeking behaviors with high functioning adults with ASD. Atypical sensory behaviors were seen at a higher rate and are in line with the increase of autistic traits in adults with ASD. Although adults with ASD experience sensory difficulties with hypo- and hyper-sensory stimuli, it can be concluded that hyper-responsiveness to stimuli would be a better way to gage and understand the differences and correlation of atypical sensory functioning adults with Autism compared to neurotypical adults. Mayer (2017) stated that adults with ASD experience a hyper-response to sensory stimuli and the sensory channels connected neurologically is difficult for the brain to cope with. Mayer (2017) found that individuals involved such therapists, researchers and clinicians should be informed on how to better accommodate individuals with ASD in their everyday environments.

The study conducted by Nesayan, Asadi Gandomani, Movallali, and Dunn (2018) included three hundred 84 preschool and elementary school children ranging in ages from four to eleven. Sampling in Tehran City was divided into five regions and children meeting specific criteria were chosen to participate in the research. It is to be noted that based on the results of the study, there was a relationship between sensory processing and behavior patterns with preschool children compared to those in the elementary school setting. Students with sensory processing difficulties experience behavioral patterns with their conduct, displaying inattentive and passive behaviors as well as hyperactivity in children. Children that have a higher sensitivity to sensory processing they exhibit more patterned behaviors. Sensory processing helps people focus their attention and responses to the environmental stimuli. Nesayan et. al (2018) states the understanding of sensory inputs are critical for activities such as learning, movement, concept formation and emotional development. Students who cannot control their difficulties with the sensory processing will more than likely display unwanted behavioral issues. Sensation seekers make sounds while they are working, are restless and are usually chewing things and exploring objects. Children with low registration are observed to be disconnected, lazy and tired, however, the children are unable to react appropriately to their environment which affects how they respond to their teacher in the classroom. Nesayan et. al (2018) found that children with ASD have difficulties following teacher’s verbal instructions, direction of movement and visual changes on the classroom board. Children with low registration may appear to be inattentive. Children with sensory difficulties display behavioral disturbances, anxiety and negative emotional responses which in correlation appear and negatively affect their conduct. Teachers must take into consideration the contribution of sensory processing patterns in relations to behaviors that affect and hinder learning. Sensory processing patterns are a significant cause too many behavioral challenges within the classroom.

Sensory-Based Intervention within the Classroom

Four school-aged children with ASD and ID participated in the study conducted by Mills, Chapparo, and Hinitt (2016). All four children attended the same special school for ASD and were in three different self-contained classrooms. The children who were selected for the study was based on teacher referrals and that demonstrated difficulties with task performance. Based on an informal assessment in each of the children’s classroom, it was determined that the atypical sensory processing was contributing to their performance difficulties within their classroom. During phase A eight elements were implemented with each student that participated in the study. The elements included supports and structured environment, individualized lesson plans, positive behavior support, curriculum, family involvement, inclusion and involvement from the multidisciplinary team. During phase B the sensory activity schedule was implemented. The two sensory activities that were used in the study was jumping on a mini trampoline and being squished under a therapy ball. The sensory activity schedule was implemented for ten minutes between their academic tasks and assignments. Three out of four participants made significant improvements with the use of the sensory activity schedule infused within a daily self-contained classroom with children that have Autism. The results also indicate that the children will benefit from a sensory activity schedule to assist them with a more positive task mastery in the classroom. Children who have atypical sensory processing scored the highest in the study. Mills et. al (2016) found that children improved when following a sensory activity schedule intervention. Mills et. al (2016) concluded that a sensory activity schedule can be used with occupational therapists that are working with children with ASD and are experiencing difficulties with sensory disorders.

Atypical Sensory Characteristics

The study investigated by Nieto, López, and Gandía (2017) sensory processing in Hispanic children who have ASD. A sensory profile was given to 45 children with sensory processing difficulties that displayed unwanted behaviors. The ages of the children were three to fourteen. Nieto et. al (2017) found that sensory processing in people with ASD were at a higher rate with percentages between 65% and 95%. Sensory processing difficulties, as well as unwanted behaviors, are universal throughout the Autism Spectrum Disorder and throughout a child’s lifetime. Parents have noted that they have observed these signs during early onset and is ultimately what led to medical professionals diagnosing their children with ASD. There are two sensory profiles which include neurological threshold and behavioral response. The four sensory patterns are seeker, avoider, sensor, and bystander. Sensory processing difficulties affect stress and anxiety in children with Autism including their families. In addition to assessing the participants in the study, the researchers also provided a questionnaire to the parents to assess their stress levels. Nieto et. al (2017) found inappropriate behaviors from children correlated with parental stress. Sensory processing difficulties and unwanted behavior correlate with one another. However, the study showed that the parents with the highest stress contributed to their high levels of sensory processing difficulties as well as unwanted behaviors in their children. The results from the study indicated and confirmed that children with ASD have more sensory processing difficulties than neurotypical children. The most prevalent unwanted behaviors displayed in the participants were sensor and avoider.

In order to better understand and improve sensory difficulties and unwanted behaviors that students with Autism experience, the study recommended developing more effective supports to children with ASD and their families.

The study was conducted by Green, Chandler, Charman, Simonoff, and Baird (2016) with 56, 946 children in South Thames with a sample of 255 children that have ASD. The children were born between the years of 1990 and 1991. The participants in this study ages ranged from 9-14. The children had educational needs as well as a variety of medical needs and diagnoses. Based on the results of this study, the children’s scores were more prevalent at 92% with having sensory difficulties in hyper or hypo sensory activity. The hypersensitivity subtype had more significance with children that have Autism compared to the control group. The score levels were significantly higher in the areas of tactile, taste/smell and visual/auditory sensitivity, and noise. In the hyposensitivity subscale, the scores did not differ much compared to the control group. The only significant difference in scores between children with Autism and the control group in the hyposensitivity subscale was that children with Autism tend to leave their clothes twisted on their body. On the emotional subscale, parents reported that their children had significant repetitive, restricted and stereotyped behavior as well as deficits in social or communication skills. Some atypical characteristics found in children that have Autism affect their enhancement of repetitive behaviors with a combination of social impairment. A lot of the sensory symptoms follow children with ASD into adulthood and have a significant impact on their daily lives.

Kirby, Boyd, Williams, Faldowski, and Baranek (2017) conducted a study included 32 children with ASD. Video data were collected in the children’s home either when they entered into the study or throughout the duration of the study that was also being funded by an Autism program in a local university. Prior to the home visitations, the parents participated in a phone interview and briefly described the sensory difficulties their children experience and any repetitive behaviors. Video recordings lasted anywhere between 45 and 60 minutes in 3 segments that were 15 minutes. The video recordings were conducted with a timeframe of 2 weeks. Based on the results, the 32 children scored within 3 types of specific behaviors that included hyperresponsiveness, sensory seeking and repetitive/stereotypic. In the observation of the sensory seeking behaviors, it was coded that the children were involved in a numerous amount of gross motor movements as well as unusual interests in the sensory aspects of their environment. In addition, with the observations of repetitive/stereotypic behaviors, it was noted that actions were with objects and the children’s bodies.

Best Practices in the Classroom with ASD Students

The study by Fishman, Beidas, Reisinger, and Mandell (2018) examined to what degree teachers are implementing evidence-based practices in their classroom. The teachers that participated in the study taught kindergarten through second grade with Autism support classrooms in Philadelphia. The teachers were trained to implement Strategies for Teaching based on Autism Research (STAR) program, which is a program with several components of evidence-based practices. Throughout the study, 4 separate evidence-based practices that were observed were: (a) positive reinforcement, (b) use of visual schedules, (c) one-to-one instruction, and (d) data collection of academic and behavioral progress. Schools are responsible for educating students that have Autism. The present study supports that evidence-based interventions can positively affect students with Autism student health such as positive behavioral intervention and supports.

Participants in the study conducted by Parsons, Miller, and Deris (2016) were 821 general education teachers in north-central Texas with at least one student with Autism in their classroom. The purpose of the study was to determine if teacher training provides teachers with the necessary classroom management tools and inclusion strategies to teach children with ASD within their classroom. The number of children diagnosed with ASD has increased over the years. The study took a closer look at how general education teachers are increasing their classroom management and inclusion strategy skills to help students with Autism function to the best of their ability with the additional support. Therefore, general education teachers are now being required to attend at least 10 hours of in-service training to keep up to par with the demands of their diverse classroom that include students with ASD. It was found in the study that student outcomes were greater when the general education teacher attended in-service training. However, the study resulted in negative outcomes for the teachers due to the lack of in-service training on classroom management and inclusion strategies to help their students with disabilities achieve success in the classroom. The general education teachers reported that they were still struggling with both academic and behavioral challenges with students with ASD in their classroom. Taking one university course assists general education teachers in acquiring the necessary tools for classroom management and inclusion strategies to use with their students on the spectrum.

In the study conducted by De Jager and Condy (2011) two ASD learners were observed in a mainstream general education classroom setting to observe the sensory processing difficulties they experienced. Observations were completed throughout a variety of settings, different ways the learners used their senses such as tactile, auditory, visual and how the learners acted and responded. Based on the results, both learners with ASD experienced the most difficulty with all sensory processing within their environment. Learners experienced sensory difficulties with their physical, cultural, social, group and task work environment. Students with ASD that are in inclusive settings who are not receiving additional support will not be successful academically or behaviorally. Teachers should be provided the proper training to assist students with ASD in their anti-social behavior and find ways to help these learners develop social and emotional strategies that will assist them in their learning environment. Educators also need to be mindful of the stereotypical pattern of behaviors students with ASD experience and try to build upon these special interests in order to embrace certain functions such as dealing with anxiety and providing sensory input.

Conclusion

The literature review supported the action research study that explored whether sensory activity schedules infused with ASD classroom best practices would benefit students and assist with their sensory processing difficulties. When calm down bottles and gel sensory bags were used, the students were able to somewhat control their sensory input and output to certain stimuli they experience throughout the day in their classrooms. Not only can these interventions be used at school they can also transfer and be used at home. This benefited students with ASD because they generalized their behaviors across all physical settings in their everyday lives.

|

Action Plan/Methods |

||||||||||||

|

Name: Kathrina Bridges School: Somerset Academy Dade |

||||||||||||

|

Research Question(s): How effective is the use of sensory activity schedules on improving a students’ ability to complete academic tasks? |

||||||||||||

|

Intervention: Describe the intervention you will implement to accomplish the outcomes you seek for your students? The interventions that were implemented were calm down sensory bottles and gel sensory bags. The outcomes for students who were to receive sensory input or output after each academic or non-preferred task that was on their daily visual schedules in order for them to regulate their sensory processing difficulties. In return, with the use of ASD classroom best practices and a sensory activity schedule, students increased their academic success.

|

||||||||||||

|

Data Collection: Describe the specific approaches you will use to collect data before, during, and/or after your intervention. You need to “triangulate” your data; thus, you need at least 3 different data sources (e.g., tests, observations, interviews). Also, be specific about what each data source measures (e.g., you are using a test that measures reading comprehension or using observation to tally bullying behaviors). Next, describe the type of data that you obtain with each source (e.g., scores from a test of subtraction facts or a frequency of bully events observed).

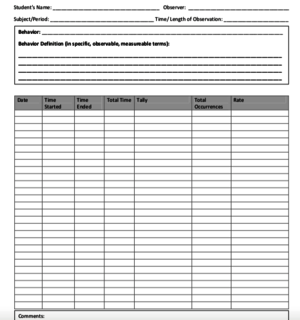

Data Source 1: Before applying the intervention, baseline data are collected on students regarding the number of behavioral incidents that occurred after each academic task in their daily schedule. When two weeks passed, the teacher graphed the data collected on a line graph to determine the frequency of students’ behaviors that affected them both socially and academically.

Data: Frequency of negative behaviors after each non-preferred/academic class on a line graph

Data Source 2: Once baseline data was collected, the sensory activity schedule was implemented, and data are collected based on the task mastery of each student that received the calm down sensory bottles and sensory gel bags interventions. This type of data collection determined if the interventions were positively affecting the students social and academic skills within the classroom. Once the intervention was completed, the teacher collected post-intervention data using the frequency chart of behaviors after each non-preferred/academic class on the same line graph. Data collection are collected on a daily basis.

Data: The Perceive: Recall: Plan and Perform System (PRPP) is a process-oriented, criterion referenced assessment that employed task analysis methods to determine problems with cognitive information processing component function during routine, task or subtask performance.

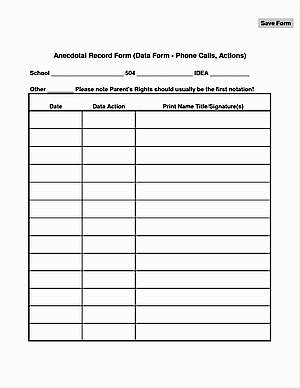

Data Source 3: Throughout the entire intervention phase, anecdotal notes were taken to ensure fidelity was being used as well as having the ability to recall information/data that may not have not been collected at the time of the intervention phase. This allowed the researcher to reflect on the process and gather enough sufficient data in order to determine if the interventions were successful.

Data: A data collection chart with a teacher observation journal was used on a daily basis. |

||||||||||||

|

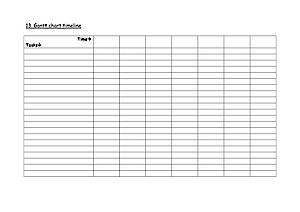

Time Line (use separate form): The Time Line must include length of intervention and when materials (if needed) are prepared, when persons are notified and/or permissions are sought, and when you plan to collect all data – be very specific.

The data collection took place over an 8-week period. Data collection started in January 2019 and ended in February 2019.

Action Plan/Methods: Timeline

|

Finding, Limitations, Implications

Data Analysis

The data collected are analyzed by comparing pre and post results from three different measures. The first measure consisted of collecting data on a frequency chart and line graph. The frequency of maladaptive behaviors were documents on a daily basis and were graphed weekly using a line graph. The data are displayed though the use of a line graph.

The second measure was the Perceive: Recall: Plan and Perform System. The stage one analysis determined the steps students took to remain on task when the intervention was being implemented inside of the classroom in accordance with their sensory activity schedule. One stage one was completed, stage two analysis began. Stage two analysis determined how each of the students functioned in different areas while the sensory activity schedule was being implemented. Stage two analyzed the areas of (a) perceive: attending, sensing, and discriminating, (b) recall: recalling facts, schemes, and procedures, (c) plan: mapping, programming, and evaluating, (d) initiating, continuing, and controlling. Data are examined on a daily basis and was graphed on a weekly basis. Results were displayed using a data table after implementing the intervention with the use of the PRPP System which is a criterion referenced assessment.

The third measure was anecdotal notes/teacher journal and a line graph. Data are collected and examined on a daily basis using a data collection chart that assessed the frequency on maladaptive behaviors. The results were displayed using a data table.

Findings

The results of the study were consistent with those previous studies conducted by Mills et. al (2016) and Fishman et. al (2018). When presented with a sensory activity schedule after each academic task, students with autism in the general education classroom setting were more likely to remain on task and complete their non-preferred activities. The intervention allowed students to have more control of their maladaptive behaviors which resulted with have a sensory break using the sensory bottles and sensory gel bags. Therefore, the students’ behaviors improved drastically while having the intervention in place. In addition to the baseline data and post data collected, the PRPP System was implemented during the intervention phase and were analyzed. The following sections provide a discussion of the results.

Frequency of Negative Behaviors

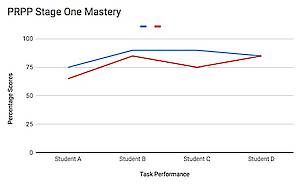

The results indicated that all of the students’ scores were above the 50th percentile with their task mastery with no sensory activity schedule in place as measured by the PRPP stage one mastery section. Why was the baseline data substantially effective during the baseline phase? As seen in Figure 1, during week 1, the four students worked on academic tasks with the general education teacher and special education teacher implementing best practices within the classroom. Frequency of negative behaviors after each non-preferred/academic class was assessed during the baseline phase. Student A scored 75%, Student B scored 90%, Student C scored 90% and Student D scored 85%. However, as seen in Figure 1, during week 2, three of the four students’ scores dropped during the baseline data collection period. Student A scored 65%, Student B score 80%, Student C scored 75% and Student D score remained the same at 85%. The indication that the scores dropped for all of the students and/or remained the same concludes that students with autism do have difficulties maintaining attention to complete academic tasks and could possibly benefit from a sensory activity schedule within the classroom. Baseline data was collected for a 2-week period.

|

— Week 1 —Week 2 |

Figure 1. Baseline data collection before SAS intervention.

Intervention Implementing the PRPP System

In Table 1, the data collected occurred during a 6-week period. During this timeframe, the sensory activity schedule was implemented for all of the students after each academic task. The students were only able to be scored during the stage two PRPP system of Recall and Plan. In order to move from quadrant to quadrant, the students must be above the 50th percentile. During the Recall quadrant students made significant improvements for recalling facts, scheme, and procedures. Table 1 displays the percentage scores the students scored during the 6-week intervention phase. During the Plan Quadrant, the data varied for each student, however, they were all performing well below average which indicated to the teachers that the students needed improvement in this area. Students were required to cope with difficult situations, understand the goal of the academic task as well as remembering it without being off task. The Plan Quadrant required the students to map, program and evaluate. Table 1 shows the data collected in the Plan Quadrant as a comparison to the students’ scores during the Recall Quadrant.

Table 1

Stage 2 PRPP Comparison of Recall and Plan Quadrant.

|

Stage 2 PRPP Recall |

Stage 2 PRPP Plan |

||||||||

|

|

Week 3 |

Week 4 |

Week 5 |

Week 6 |

|

Week 3 |

Week 4 |

Week 5 |

Week 6 |

|

Student |

|

|

|

|

Student |

|

|

|

|

|

A |

90% |

90% |

85% |

90% |

A |

50% |

40% |

45% |

45% |

|

B |

80% |

75% |

90% |

75% |

B |

40% |

45% |

50% |

50% |

|

C |

90% |

80% |

100% |

85% |

C |

35% |

40% |

45% |

40% |

|

D |

75% |

90% |

70% |

90% |

D |

50% |

45% |

50% |

40% |

Teacher Observation Journal

The teacher used an observation journal to document the behaviors the students displayed during the baseline and intervention phases of the data collection. As seen in Table 2, the students displayed some maladaptive behaviors while only having classroom best practices implemented after each academic task. Demands were not placed or requested from the students during the baseline data collection phase. However, during week 2, the teacher did observe that the students began showing more signs on maladaptive behaviors after each academic task. Once the teacher implemented the sensory activity schedule for each student during weeks 3 through 6, the students were focused, attended to tasks, participated, self-regulated, and made progress. The teacher noted that the data collected are during the stage 2 recall quadrant of the PRPP system. Once, the students entered into the stage 2 plan quadrant of the PRPP system, the students’ maladaptive behaviors increased substantially. The stage 2 plan quadrant proved to be difficult for the students to achieve success.

Table 2

Teacher Observation Journal

|

|

Weeks |

|

Observations During Academic Tasks

|

|||

|

|

|

Student’s behaviors |

|

Teacher’s feelings |

||

|

Baseline |

1 |

Focused, some repetitive body movements |

|

Enthusiastic, confident, and excited |

||

|

|

2 |

Increase in repetitive body movements, distracted, some interruptions |

|

Slightly disappointed and frustrated |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Teacher’s feelings |

||

|

|

|

Stage 2 Recall |

Stage 2 Plan |

Stage 2 Recall |

Stage 2 Plan |

|

|

Intervention |

3 |

Focused, attended to tasks, participation, self-regulated, made progress |

Interruptions, repetitive body movements, inattention, off-task |

Calm, focused, excited, hopeful, patient, and enthusiastic. |

Frustrated, dissatisfied, ineffective, exhausted, unproductive, and disappointed. |

|

|

|

4 |

Focused, attended to tasks, participation, self-regulated, made progress |

Interruptions, repetitive body movements, inattention, off-task |

Calm, focused, excited, hopeful, patient, and enthusiastic. |

Frustrated, dissatisfied, ineffective, exhausted, unproductive, and disappointed. |

|

|

|

5 |

Focused, attended to tasks, participation, self-regulated, made progress |

Interruptions, repetitive body movements, inattention, off-task |

Calm, focused, excited, hopeful, patient, and enthusiastic. |

Frustrated, dissatisfied, ineffective, exhausted, unproductive, and disappointed. |

|

|

|

6 |

Focused, attended to tasks, participation, self-regulated, made progress |

Interruptions, repetitive body movements, inattention, off-task |

Calm, focused, excited, hopeful, patient, and enthusiastic. |

Frustrated, dissatisfied, ineffective, exhausted, unproductive, and disappointed. |

|

Overall, the students did maintain appropriate classroom behaviors during the PRPP stage one mastery as well as during the Recall Quadrant of the PRPP system. However, the students did display maladaptive behaviors during the Plan Quadrant which required more complex thinking, focusing and remaining on task. Students would benefit greatly from a sensory activity schedule on a long-term basis to be able to complete more difficult tasks that are found within the Plan, Perform and Perceive Quadrants.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. The length of the study was limited to eight weeks due to Spring Recess, Florida State Assessments (FSA), and Stanford Achievement Tests (SAT-10). There were several interruptions throughout the school week such as meetings, absences, early dismissals, assemblies, and dances. The use of video recording for data collection was a limitation due to the time restraints traveling in between two different classrooms as a collaboration teacher. It was not feasible to determine whether greater gains could have been achieved during a longer intervention period. The sample size presented a limitation. Four students were included in the sample who were diagnosed with autism compared to the seven students who the collaboration teacher had on the caseload.

Implications

Sensory activity schedules can benefit children if they are implemented with fidelity inside of the classroom on a long-term basis. Sensory schedules can help students with autism build connections in their brains, this allows the student to increase their ability to complete more complete academic tasks. As seen in stage two of the Plan Quadrant, all of the students’ scores were well below the 50th percentile. This quadrant required students to engage in more complex thinking in order to achieve more complex tasks inside of the classroom. The students had great difficulty in this area and is something to work on in the future. Another benefit that sensory schedules can positively affect students with disabilities are that it assists them with cognitive growth and problem-solving skills. These are skills that students need to improve on in order to be able to master the four quadrants in the PRPP system. Overall, this study should be completed with a larger sample size as well as a longer period of baseline data and implementation of the intervention phase.

Dissemination

Findings from the study were shared with administration and the general education teachers the exceptional student education (ESE) teacher collaborated with. Additionally, results of the study were shared with Florida International University (FIU) graduate students and professors through a poster presentation session.

References

Adamson, A., O’Hare, A., & Graham, C. (2006). Impairments in Sensory Modulation in Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(8), 357-364. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/03080226060690080

De Jager, P., & Condy, J. (2011). The identification of sensory processing difficulties of learners experiencing Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) in two mainstream Grade R classes. South

African Journal of Childhood Education,1, 11-26.

Fishman, J., Beidas, R., Reisinger, E., & Mandell, D. S. (2018). The utility of measuring intentions to use best practices: A longitudinal study among teachers supporting students with autism. Journal of School Health, 88(5), 388-395.

Gonthier, C., Longuépée, L., & Bouvard, M. (2016). Sensory processing in low-functioning adults with autism spectrum disorder: Distinct sensory profiles and their relationships with behavioral dysfunction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(9), 3078-3089. doi:https://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1007/s10803-016-2850-1

Green, D., Chandler, S., Charman, T., Simonoff, E., & Baird, G. (2016). Brief report: DSM-5 sensory behaviors in children with and without an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(11), 3597-3606. doi:https://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1007/s10803-016-2881-7

Kirby, A. V., Boyd, B. A., Williams, K. L., Faldowski, R. A., & Baranek, G. T. (2017). Sensory and repetitive behaviors among children with autism spectrum disorder at home. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 21(2), 142-154. doi:https://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1177/1362361316632710

Mayer, J. L. (2017). The relationship between autistic traits and atypical sensory functioning in neurotypical and ASD adults: A spectrum approach. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(2), 316-327. doi:https://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1007/s10803-016-2948-5

Mills, C., Chapparo, C., & Hinitt, J. (2016). The impact of an in-class sensory activity schedule on task performance of children with autism and intellectual disability: A pilot study. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(9), 530-539. doi:https://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1177/0308022616639989

Nesayan, A., Asadi Gandomani, R., Movallali, G., & Dunn, W. (2018). The relationship between sensory processing patterns and behavioral patterns in children. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools & Early Intervention, 11(2), 124-132. doi:https://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1080/19411243.2018.1432447

Nieto, C., López, B., & Gandía, H. (2017). Relationships between atypical sensory processing patterns, maladaptive behavior and maternal stress in Spanish children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61(12), 1140-1150. doi:https://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1111/jir.12435

Parsons, L. D., Miller, H., & Deris, A. R. (2016). The effects of special education training on educator efficacy in classroom management and inclusive strategy use for students with autism in inclusion classes. Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals, 1-10.

Sweet, M. (2010). Helping Children with Sensory Processing Disorders: The Role of

Occupational Therapy. Odyssey: New Directions in Deaf Education,11(1), 2022.

Tomcheck, S. D., & Dunn, W. (2007). Sensory Processing in Children with and Without Autism:

A Comparative Study Using the Short Sensory Profile. American Journal of Occupational Therapy,61(2), 190-200. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.190

Appendix A

Administrative Consent for Action Research

Appendix B

Data Collection Frequency Recording Form

Appendix C

The PRPP System Scoring Sheet

(Image in PDF File)

Appendix D

Chart Timeline

Chart Timeline

Appendix E

Anecdotal Record Form

To download a PDF file version of this issue of NASET’s Autism Spectrum Disorder Series: CLICK HERE

To return to the main page for NASET’s Autism Spectrum Disorder Series – Click Here