By Buruuj Tunsill, Ed.S

Florida International University

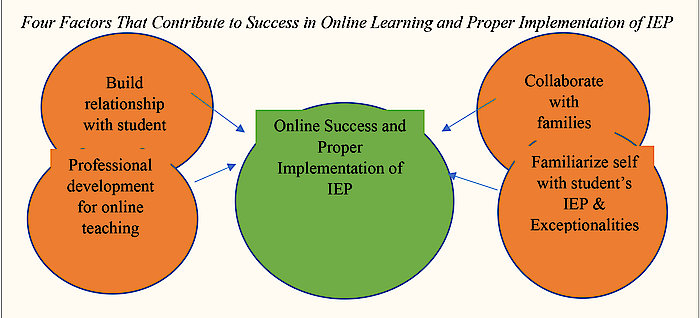

This issue of NASET’s IEP Components series was written by Buruuj Tunsill, Ed.S. A global pandemic placed a strain on many educators across the world, educators and students alike had to suddenly switch to a different mode of education–online learning. Online learning is when students receive instruction through synchronous or asynchronous interactions via the internet (Rice & Carter, 2015). Without professional training, educators were expected to deliver all lessons virtually to all students, which includes students with disabilities. Prior to the pandemic, educators have had difficulties implementing individualized education plans for students with disabilities. The research identifies key issues that impact educators who teach culturally and linguistically diverse students via online learning and provide recommendations for how special educators and other practitioners can better serve culturally and linguistically diverse students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Thought fictitious scenarios incorporating Yessenia and Shawn, issues that may negatively influence online learning experiences will be examined to determine the best approaches to resolving the issues in an online learning setting. There were four identified factors that can contribute to culturally and linguistically diverse students with disabilities online success and proper implementation of their rep: Collaborate with families, build relationship with student, familiarize yourself with students’ IEP and exceptionalities, and professional development for online teaching.

Individualized Education Plans and Implementation in Urban Schools via Distance Learning

Abstract

A global pandemic placed a strain on many educators across the world, educators and students alike had to suddenly switch to a different mode of education–online learning. Online learning is when students receive instruction through synchronous or asynchronous interactions via the internet (Rice & Carter, 2015). Without professional training, educators were expected to deliver all lessons virtually to all students, which includes students with disabilities. Prior to the pandemic, educators have had difficulties implementing individualized education plans for students with disabilities. The research identifies key issues that impact educators who teach culturally and linguistically diverse students via online learning and provide recommendations for how special educators and other practitioners can better serve culturally and linguistically diverse students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Thought fictitious scenarios incorporating Yessenia and Shawn, issues that may negatively influence online learning experiences will be examined to determine the best approaches to resolving the issues in an online learning setting. There were four identified factors that can contribute to culturally and linguistically diverse students with disabilities online success and proper implementation of their rep: Collaborate with families, build relationship with student, familiarize yourself with students’ IEP and exceptionalities, and professional development for online teaching.

Shawn is a 6th grade African American student with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and is fully included in a general education setting via online learning with his peers. During his first class session online, Shawn continuously turned his camera on and off, laid down on the couch multiple times, and walked away from the computer without being excused. Shawn’s mother complained that the teacher was not following his individualized education plan (IEP) and did not provide Shawn with adequate breaks to stretch or time to engage in a preferred academic activity. Also, his mother mentioned that she heard Shawn’s teacher, Ms. Jackson, yelling at him to pay attention while she was engaging in a whole group reading activity. Shawn’s mother brought her concerns to the school’s education specialist’s attention and after a conference with Ms. Jackson, principal, and education specialist, they all agreed that Ms. Jackson and Shawn’s mother will collaboratively meet once every week to discuss Shawn’s progress and express any concerns in order to promote Shawn’s academic achievement.

Yessenia is a 6th grade Hispanic student with a learning disability in reading and is placed in a remote general education setting with 30-minute pull outs three times a week with the special education support facilitator. She is on a first grade reading level with basic phonemic awareness skills; she can blend three- and four-letter words, but she struggles with multisyllabic words. Yessenia has been in school for two months now via online learning but cannot keep up with the pace of the teacher and has failed every reading assessment administered to her. Yessenia’s teacher, Mrs. White, complains to the support facilitator that she does not understand why Yessenia does not ask for help when she is instructing or why she doesn’t ask for her to clarify questions or assignments. The support facilitator shares her experiences with Yessenia to Mrs. White and explains to her, although Yessenia is a C2 English Language Learner (ELL) that she still has difficulty engaging online because the only language spoken at home is Spanish. She also explains to Mrs. White that Yessenia is very shy. Due to Mrs. White’s expressed concerns, the ESE support facilitator agreed to take an extensive look at Yessenia’s IEP with her as well as collaborate with her twice a week to offer tips on how to engage with Yessenia and provide instructional strategies.

In the spring of 2020, a ferocious virus called Coronavirus, popularly known as CoVid-19, began to spread across the world and as a result, many schools had to shut down. The CoVid-19 pandemic placed a strain on many educators, parents, and students. During unprecedented times, educators had to unexpectedly convert from brick-and-mortar schooling to fully online learning. Online learning is when students receive instruction through synchronous or asynchronous interactions via the internet (Rice & Carter, 2015). Without professional training, educators were expected to deliver all lessons virtually to all students, which includes students with disabilities. Both Shawn and Yessenia are students with disabilities who are expected to engage in fully online courses and educators are expected to properly deliver accommodations and modifications for these students. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), students with disabilities include intellectual disabilities, hearing impairments, speech or language impairments, visual impairments, serious emotional disturbance, orthopedic impairments, autism, traumatic brain injury, other health impairments, and specific learning disabilities (U.S. Department of Education, 2019). Students with disabilities are protected under the IDEA law, which is a law that ensures all children with disabilities have access to a free appropriate public education (FAPE), educators and parents have the necessary tools to improve educational results, and students with disabilities rights are protected (U.S. Department of Education, 2019). Educators are required to adhere to each child’s individualized education plan (IEP). IEPs were created to help teachers offer students appropriate accommodations and modifications to students in their least restrictive environment (LRE). However, IEPs are not always followed with fidelity. Yessenia and Shawn’s teachers were supposed to fully examine their IEPs to make certain they understood their personality traits and were providing the necessary services. According to Crawford and Ketterlin-Geller (2013), when it comes to testing accommodations, educators tend to make decisions based on intuition and rarely considered empirical data.

IEP implementation presents many challenges for educators in the United States. Some issues include but are not limited to varying quality of services, special educator shortage, unsatisfactory school-family relationships, difficulties collaborating with families from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, and some families feeling isolated or marginalized during IEP meetings (Sacks & Halder, 2017; Zagona, et al., 2019). Forty-one percent of special education students are from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (Sacks & Halder, 2017). According to one study, an unequal quality of services is frequently delivered to students of different socioeconomic statuses, races, ethnicities, and levels of English proficiency (Kalyanpur, 2008). To add to the myriad of issues contributing to the incorrect implementation of IEPs, there is a shortage of special education teachers in 49 out of 50 states and as a result, many personnel would ineffectively implement IEP goals for students (Sacks & Haider, 2017). If educators have a difficult time properly implementing accommodations or modifications to students in brick-and-mortar schools, how are they faring when it comes to online learning?

Furthermore, there were reported difficulties before the pandemic with distance learning and students with disabilities. Some educators reported that laws and policies were ill-equipped to deal with online learning and the pace of coursework (Rice & Carter, 2015). In general, teachers have found it difficult to properly service all students with disabilities (Crawford & Ketterlin-Geller, 2013; Rice & Carter, 2015). According to Shah (2011), many full-time online schools do not have the capability to sufficiently accommodate students with moderate to severe disabilities. During the CoVid-19 pandemic, students across America suffered from significantly reduced IEP-related services; specifically, Chicago publicly admitted to parents that the full number of minutes identified on their children’s IEPs could not be adhered to while the students were working remotely (Easop, 2022). So, how is it for educators who service culturally and linguistically diverse students with disabilities via distance learning at underfunded schools? According to Honda (2013), poorer communities collect lower property taxes; as a result, there is less money that can be spent on school facilities, educational curriculum, and staff. Hence, it is suggested that underfunded schools may have a harder time ensuring that all students have sufficient technology for virtual learning to successfully take place. Also, usually underfunded schools are filled with students from low-socioeconomic statuses and as a result, many students may not have access to internet. One in four adolescents with a household income of less than $30,000 lack access to a computer at home (Auxier &Anderson, 2020). One-third of low-income households with school age children do not have access to high-speed internet (Auxier & Anderson, 2020). Nevertheless, even with internet parents with low income lack the time due to their work schedules to support their child via distance learning at home (Catalano et al., 2021). While educators may not be able to control factors such as students’ access to internet and technology, there are practical solutions for special educators as well as general educators on how to better serve culturally and linguistically diverse students from low socioeconomic backgrounds via online learning and ensure that they receive the best engagement as possible.

Therefore, the purpose of this research is to identify key issues that impact educators who teach culturally and linguistically diverse students via online learning and provide recommendations for how special educators and other practitioners can better serve culturally and linguistically diverse students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Through fictitious scenarios incorporating Yessenia and Shawn, issues that may negatively influence online learning experiences will be examined to determine the best approaches to resolving the issues in an online learning setting. There are four identified factors that can contribute to culturally and linguistically diverse students with disabilities online success and proper implementation of their IEP (Figure 1): Collaborate with families, build relationship with student, familiarize yourself with student’s IEP and exceptionalities and professional development for online teaching (McDevitt & Mello, 2021; Crouse et al., 2018; Repetto, Cavanaugh et al., 2010).

Research focused on culturally and linguistically diverse students and online learning in New York City revealed that parents appreciate when educators actively listen to their advice concerning their child and treat them as if they have a certain level of expertise as a parent (McDevitt & Mello, 2021). In McDevitt & Mello (2021), a few mothers working with a preservice teacher via online for the success of their child expressed that they really like the fact that the teachers listen to their input and experience. In addition, preservice teachers were encouraged by parents’ enthusiasm and active involvement from the beginning and the preservice teachers made sure that they positioned themselves as learners (McDevitt & Mello, 2021). The preservice teachers took a keen interest in the students’ needs, areas that needed to be targeted, and progression (McDevitt & Mello, 2021). According to one study, making decisions for children with disabilities requires collaboration, communication, and respect between every adult involved in the process (Collier et al., 2015). As shown in another study, collaboration contributed to the student’s online learning success. One experience of a preservice educator, the student continuously ran from the screen and laying on the couch however, due to the collaboration with his mother and building a close relationship resulted in a positive learning experience for the student (McDevitt & Mello, 2021). Likewise, frequent communication with parents is imperative for students with disabilities success. In one study, teachers who were teaching online reported that they made additional efforts to contact parents of children with disabilities so the parent could assist their child and teachers supported parents in troubleshooting technology as well as aided with certain computer skills (Crouse et al., 2018). It is important for educators to collaborate with families to meet students’ cultural needs (McDevitt & Mello, 2021) and to take time to see parents’ perspective (Collier et al., 2015).

After Shawn’s mother spoke with Ms. Jackson, the ESE specialist, and principal concerning Ms. Jackson’s failure to acknowledge Shawn’s off tasks behaviors appropriately. Ms. Jackson started making greater efforts in paying close attention to Shawn’s needs and following his IEP services. For every 20 minutes Shawn displayed on task behaviors, he was allowed to visit his favorite reading website and listen to a read-aloud book for no longer than 10 minutes and his mother monitored his time. Shawn’s behaviors began to improve, he stopped turning the camera on and off. However, sometimes he still would walk away from the camera to lay on the couch.

Shawn’s behavior improved because the mother and Ms. Jackson were collaborating, but he still displayed some off-tasks behaviors (i.e., laying on the couch). Ms. Jackson had other students to attend to so she could not always immediately redirect Shawn. One approach that can help decrease the number of times Shawn walks away from the computer is collaboration among stakeholders. During a collaborative meeting, Ms. Jackson and Shawn’s mother determined that it is best that Shawn stands up as frequently as needed and pace back and forth in proximity of the computer when he is not actively working on an assignment and the mother agreed to monitor him to make sure he does not go too far away from his working area. With the new accommodations, Shawn’s class participation improved, and he begin to pay closer attention to Ms. Jackson’s instruction.

Students without disabilities such as ADHD may be able to sit down for prolonged periods and pay close attention to directions via online learning without the assistance of an adult or parent. Oftentimes, the extra support for students with disabilities is needed in order for them to have a positive online learning experience and proper accommodations and modifications as outlined on their IEPs must be followed.

Build Relationship with Student

In McDevitt & Mello (2021), the preservice teachers explained that building a relationship with the student was imperative to engaging them in online instruction. They further explained that cultivating genuine relationship with student was key to increasing engagement online (McDevitt & Mello, 2021). The students expressed that they enjoyed their online experience because of the personal attention that they received (McDevitt & Mello, 2021). It is important the teacher build effective communication between the learner and instructor (Amka & Dalle, 2022). Cognitive presence has a positive and significant effect on students with disabilities satisfaction with the online learning experience and the course design should engage learners (Amka & Dalle, 2022). Additionally, a study conducted with 24 participants who were diagnosed with a learning disability or ADHD found that when students utilized a system with an agent with emotionally affective behavior versus a system with an agent with neutral behavior that students’ communication improved (Chatzara et al., 2016). Students were able to complete learning tasks and performance successfully via online learning (Chatzara et al., 2016). Hence, it is suggested that showing true empathy and building authentic relationships with students with disabilities can increase their productivity.

Yessenia’s participation in classroom reading activities started to improve once Mrs. White decided to spend class time getting to know her students through interactive activities. She made sure she acknowledged Yessenia multiple times throughout her discussions and took anecdotal notes of her conversations with Yessenia. Yessenia began to step outside of her comfort zone and work in small groups with peers. She placed Yessenia in a heterogenous group with at least one dual language Spanish speaker with hopes of Yessenia grasping stronger reading skills. Yessenia’s interactions were improving, but she was still struggling with expressing concerns when it came to reading assignments and her grades in reading were suffering.

Yessenia’s issues with expressing herself can be found in many timid students with disabilities. Also, Yessenia’s difficulties reveal the importance of educators building effective relationships with their students from the beginning so the student can feel comfortable with coming to them for any questions or concerns. Mrs. White started to build a relationship with Yessenia through interactive activities, but it would be best for Mrs. White to take an extra step and schedule some one-on-one time with Yessenia via a breakout room (i.e., a room separate from classmates) so Yessenia can openly express her concerns without the distraction of her general education peers.

Mrs. White asked the support facilitator to enter her virtual room and monitor her other students so she can talk to Yessenia privately. Yessenia and Mrs. White spent 15 minutes talking and Mrs. White finally understood that Yessenia was having a difficult time during her reading assessments because of the length of the test and timeframe of completion. Mrs. White recalled after her sit down with the ESE support facilitator that Yessenia accommodations allow her to receive additional time during tests and there’s a read-to-text feature in her virtual classroom that can be utilized to aid in Yessenia’s understanding of the text during independent reading activities. Also, Mrs. White started to pull Yessenia out twice in a small group for intensive reading instruction in fluency. Mrs. White swiftly made changes to Yessenia’s classroom experiences and Yessenia’s reading outcomes started to improve slowly and steadily.

Students with a reading learning disability in intermediate grades have a difficult time keeping up with grade-level peers because it impairs comprehension, reduces motivation to read, and makes it difficult for children to keep up with reading demands in their classes (LD Online, 2005). It was imperative for Mrs. White to talk to Yessenia about her issues and make efforts to resolve the issues in order to provide Yessenia with better and more intensive reading support.

Familiarize Yourself with Student’s IEP and Exceptionalities

In McDewitt & Mello (2021), the preservice educators lacked knowledge on their student’s disability. In one instance, one preservice educator was working with a student who had limited verbal abilities and had to learn to communicate with the student with the help of her mother (McDewitt & Mello, 2021). Through trial and error, the preservice educator was able to develop instructional strategies. Likewise, another preservice educator was unfamiliar with students with autism and through collaboration learned to successfully work with her student (McDewitt & Mello, 2021). In many inclusion settings, educators are presented with an IEP, but rarely sit down to examine the IEP or even reach out to a specialist or a support facilitator to better understand the IEP, which is why it sometimes can be difficult for a child with a disability to successfully engage in learning especially online. As mentioned in one study, one teacher explained that when she worked in a brick-and-mortar setting that she hardly ever communicated directly with special education teachers for making modifications and accommodations, she would simply get a copy of the student’s IEP and the ESE support facilitator would say, “let me know if you need anything,” but no one had the time to actually sit down and talk (Crouse et al., 2018). However, in the same study, the teacher worked online and was provided with a case manager for her students with disabilities and anytime she needed help with making modification she can get online to meet the case manager (Crouse et al., 2018). Understanding the child’s IEP as well as the child’s disability is a crucial factor in properly implementing the student’s accommodations and modifications.

Shortly after Ms. Jackson sat down in a conference with Shawn’s mother and the ESE specialist, she took the time to review Shawn’s IEP and highlighted Shawn’s goals so she can quickly refer to his IEP as needed while she is teaching and so she can keep accurate data on his progress towards his goals. Shawn continued to remain engaged with a flexible setting where he was allowed to move as needed, but when it came time for Shawn to take mid-year exams, Shawn did not do too well.

Ms. Jackson reviewed Shawn’s IEP and made note of his IEP’s goals, but she failed to review Shawn’s IEP in its entirety. Ms. Jackson gave Shawn breaks as needed during the test and allowed him to stand as needed. By collaborating with Shawn’s mother, Ms. Jackson had a better understanding of Shawn’s needs, however, it is important for educators to review accommodations on the IEP as well as goals. After reviewing the IEP again with Shawn’s mother, Ms. Jackson noticed that Shawn is entitled to time in a half (i.e., more than double the time so if his general education peers were given 60 minutes for an assessment, he should have been given 150 minutes). Also, directions, questions, and answers could have been read to him. After explaining the situation to the ESE specialist, Ms. Jackson rescheduled the test for Shawn and provided all his accommodations. Shawn score went form a 43% to a 72% on the standardized assessment.

All educators working with students with disabilities should carefully review every part of a student’s IEP and make note of all student’s accommodations, goals, modifications, supplemental aids, and read the summary of the child’s academics, behavioral, communication, and independent functioning skills. Educators should carefully evaluate the IEP at the beginning of the year so they can be well prepared and be able to handle and resolves any issues without uncertainties.

Professional Development

For educators to effectively implement strategies via online, they must be well prepared and attend professional development workshops to acquire necessary skills when working online with at-risk youth (Repetto et al., 2010). Professional training has been proven to improve the quality of education for all students and not just students with disabilities (Pisha & Coyne, 2001) and most educators have little or no experience working with students with disabilities especially in an online setting (Rice et al., 2008). A nationwide survey conducted in 2008 found that online schoolteachers needed more training in modifying, customizing, and/or personalizing assignments to address diverse learning styles than educators who worked in a brick-and-mortar setting (Rice et al., 2008).

Shawn is progressing and Ms. Jackson and Shawn’s mother are finally on the same page. Ms. Jackson listens to Shawn’s mother’s concerns during their collaborative meetings and Shawn’s mother provides support as needed at home. However, Ms. Jackson is still having a difficult time finding the best resources to cultivate Shawn’s interest in math.

Likewise, Mrs. White is having a difficult time with finding fun, interactive online reading programs for Yessenia. Yessenia is showing improvement, but Mrs. White wants her to remain engaged even when she is not working in small groups or one-on-one with Mrs. White.

Ms. Jackson and Mrs. White decided to attend monthly virtual professional training sessions to improve their knowledge on various academic programs for math and reading so they can better serve their students. After a few months, Shawn became more engaged in math with the help of an interactive online math program and with a new online reading program, Yessenia’s ability to blend multisyllabic words improved.

It is important for educators to recognize gaps in their students’ learning and try to find the best ways to remedy any issues that may interrupt their students’ progress. Professional development sessions can be utilized to help educators improve their students’ online experiences.

Conclusion

Research concerning culturally and linguistically diverse students with disabilities and online learning is limited. However, the research provided reveals that while there are uncontrollable factors when it comes to working with CLD students with disabilities from low-socioeconomic backgrounds such as lack of access to high-speed internet and technology (Auxier & Anderson, 2020) there are some factors that are within educators’ control that can help improve children with disabilities’ overall experiences with online learning (i.e., collaborating with families, building relationship with students, familiarizing yourself with students’ IEPs and exceptionalities, and attending professional development sessions) (McDevitt & Mello, 2021; Crouse, Rice, & Mellard, 2018; Repetto, Cavanaugh, Wayer, & Liu, 2010).

Figure 1

Collaborate with Families

References

Amka, A. and Dalle, J. (2021). The satisfaction of the special need’ students with e-learning

experience during covid-19 pandemic: A case of educational institutions in Indonesia. Contemporary Educational Technology, 14(1), ep334. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/11371

Auxier, B., and Anderson, M. (2020, March 16). As schools close due to the coronavirus, some

U.S. students face a digital ‘homework gap.’ Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/16/as-schools-close-due-to-the-coronavirus-some-u-s-students-face-a-digital-homework-gap/#:~:text=Some%2015%25%20of%20U.S.%20households%20with%20school-age%20children,households%20are%20especially%20likely%20to%20lack%20broadband%20access.

Burdette, P., Greer, D., and Wood, K. (2013). K-12 Online learning and students with

disabilities: perspectives from state special education directors. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17(3) 65-72.

Carter, R., and Rice, M. (2015). ‘When we talk about compliance, it’s because we lived it’

online educators’ roles in supporting students with disabilities. Online Learning,

19(5) 18-36.

Catalano, A., Torff, B., and Anderson, K. (2021). Transitioning to online learning during the

COVID-19 pandemic: differences in access and participation among students in disadvantaged school districts. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 38(2), 258-270. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-06-2020-0111

Chatzara, K., Karagiannidis, C., and Stamatis, D. (2016). Cognitive support embedded in self-

regulated e-learning systems for students with special learning needs. Education and Information Technologies, 21(2), 283-299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-014-9320-1

Collier, M., Keefe, E. B., and Hirrel, L.A. (2015). Preparing special education teachers to

collaborate with families. The School Community Journal, 25(1), 117-135. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/preparing-special-education-teachers-collaborate/docview/1696234431/se-2

Crawford, L. and Ketterlin-Geller, L.R. (2013). Middle school teachers’ assignment of test

accommodations. The Teacher Educator, 48(1) 29-4 https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2012.740152.

Crouse, T., Rice, M., and Mellard, D. (2018). Learning to serve students with disabilities online:

Teachers’ perspectives. Journal of Online Learning Research, 4(2), 123-145. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1184994

Easop, B. (2022). Education equity during COVID-19: Analyzing in-person priority policies for

students with disabilities. Standard Law Review, 74(1), 223-275. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/education-equity-during-covid-19-analyzing-person/docview/2634890984/se-2?accountid=10901.

Honda, M. (2013). Education equity: Where we are and where we need to be. Asian American

Policy Review, 23 11-20.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. Chapter 33 (2004).

Kalyanpur, M. (2008). The Paradox of majority underrepresented in special education in India.

The Journal of Special Education, 42(1) 55-64 https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466907313610.

LD Online (2005). Components of Effective Reading Instruction Retrieved from

https://www.ldonline.org/ld-topics/teaching-instruction/components-effective-reading-instruction

McDevitt, S.E., and Mello, M.P. (2021). From crisis to opportunity: Family partnerships with

special education preservice teachers in remote practicum during the COVID-19 school closures. School Community Journal, 31(2), 325-346. https://www.schoolcommunitynetwork.org/SCJ.aspx

Pisha, B. and Coyne, P. (2001). Smart from the start: The promise of universal design for

learning. Remedial and Special Education, 22(4), 197-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193250102200402

Repetto, J., Cavanaugh, N., Wayer, N., and Liu, F. (2010). Virtual high schools: Improving

outcomes for students with disabilities. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 11(2), 91-104. (PDF) Virtual high schools: Improving outcomes for students with disabilities (researchgate.net)

Rice, K., Dawley, L., Gasell, C., & Florez, C. (2008). Going Virtual! Unique Needs and

Challenges of K-12 Online Teachers. Department of Educational Technology.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242575332

Sacks, L., and Halder, S. (2017) Challenges in implementation of individualized education plan

(IEP): Perspectives from India and United States of America. India Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 8(9) 958-965.

Shah, N. (2011). eLearning access for special-needs students. Education Week, 32(1), S2-S4.

Zagona, A. L., Miller, A. L., Kruth, J.A., and Love, H.R. (2019). Parent perspectives on special

education services: How do schools implement team decisions? School Community Journal, 29(2), 105-128. https://hdl.handle.net/1808/29944

About the Author

Buruuj Tunsill is a doctoral candidate at Florida International University. Her research interests focus on distance learning, racially ethnically, and linguistically diverse students’ needs, and collaborating with families of students with diverse needs. She is a funded scholar on Project INCLUDE which is an OSEP 325D project that provides fellowships to qualified doctoral students. Prior to becoming a full-time PhD student, Buruuj taught for five years at underserved schools where her primary focus was on students with emotional behavioral disorders. Buruuj received her M.S. in Special Education from Florida International University. She received her BA in Communication and Culture with a concentration in Legal Communications from Howard University.

Download this Issue

To Download a PDF file version of this Issue of the NASET’sIEP Components Series – CLICK HERE